July 20, 2012

The Once & Future Library

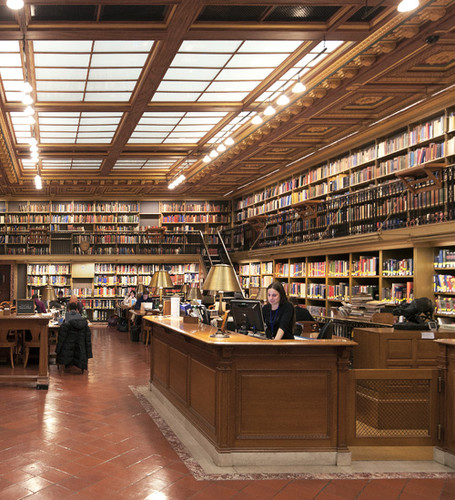

Room 300, home of the art & architecture collection, of the NYPL. Photo: Norman McGrath

The future is now, the saying goes, and for those of us who live and work in the world of letters, that maxim rings especially true. Tablets and e-readers and the overwheming availability of digitized content are transforming the way we consume information, the kinds of information we consume, and—not least of all—the places in which we do that consumption. Just how libraries are adapting to this new world of information is the subject of my cover story for the July issue of Metropolis, a piece prompted by the contested plans to dramatically redesign, both intellectually and physically, the main research library of the NYPL.

Although it’s tempting to think that the “future is now,” one of the realities about which I write is that the future is still in the future. We live in a time of competing technologies, and just how these will shake out in 2 or 5 or 10 years is anything but clear. While the Internet offers an enormous amount of content, it is disorganized, subject to randomness, and absent equally enormous amounts of material that has not been and may never be scanned. As one scholar told me, “Google has the problem that it’s an index from nowhere, and it’s not even a good index.” Predicting the future is hard, and libraries have a pretty dubious record. The NYPL only recently bet big on CD-ROMs for its Science Industry and Business Library (SIBL). Now it wants to close that building, as part of its restructuring.

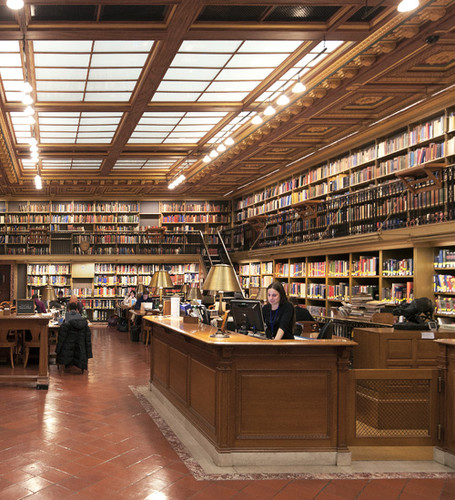

High density stacks at Mansueto Library. Photo: Tom Rossiter

This should suggest a somewhat cautious path, and this in fact characterizes the most sophisticated new research library, the University of Chicago’s recent Mansueto Library, designed by Helmut Jahn as an appendage to the school’s primary research facility, a 1970s concrete bunker by SOM. The genius of Mansueto is that it holds books in high-density pallets retrieved by automated cranes, allowing it to serve books with extreme rapidity. But this library of the future was designed only to serve the library’s needs for a few decades; it is, essentially, an interim solution until the future actually arrives.

It’s also worth noting that while many are anxious to proclaim the death of the library, we seem to be building more of them than ever, and they seem to be playing ever more central roles in our communities, even if their primary functions are not longer to serve books to readers.

In any case, I hope you will read the story.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Mark Lamster

Related Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

Recent Posts

Candace Parker & Michael C. Bush on Purpose, Leadership and Meeting the MomentCourtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging Why scaling back on equity is more than risky — it’s economically irresponsibleRelated Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays