May 18, 2006

The Photography of Mark Robbins

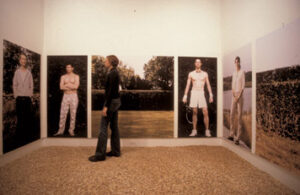

Mark Robbins exhibition at Atlanta Center for Contemporary Art, 2003

Mark Robbins’ Households is a collection of portraits in which the sitters are sometimes sitting rooms (or kitchens or bedrooms), and the people are polished, draped, and arrayed like furniture. Composed to resemble architectural plans or elevations — or in some cases the triptychs of medieval altarpieces — the images represent home dwellers and their environments. Flesh, bone, brick, stone, contoured torsos, and varnished chairs assume equal status. The message is simple: You may not be what you eat, but you most certainly are where you live.

This statement about identity has been haunting homemakers for more than a century like a fidgety wraith. It’s trumpeted with fanfare by shelter magazines, big-box stores, reality TV programs, and e-commerce sites. “Thousands of ways to make your home more YOU!” boasts the cover of a recent IKEA catalog, a publication whose magazine-like format, complete with headlines, signals not only the correspondence between self and domicile, but also the increasingly blurry boundaries between showing and selling. The tagline of the popular magazine Real Simple is “Life/Home/Body/Soul,” the word separated by slashes to stress their equality.

Indeed, more and more magazines are collapsing themes of self- and home improvement in order to provide instruction manuals for living. Martha Stewart Living and Southern Living are just two periodicals that bare that objective in their titles. And with a growing number of retail channels hawking affordable goods to a global market, the promise of continual self-invention through home design multiplies. The dream on offer is one of a perpetual adolescence with the license to live as anything — austere, morose, sociable, glamorous, high-tech, tweedy, or Moroccan — and commit to nothing. Rustics can shop for faux-antique farm tables at ABC Carpet & Home in Manhattan or scour eBay for authentically gouged furniture. Postmodernists can ferret out Michael Graves’s florid, colorful products for Target or await the return of Memphis, the 1980s Italian design movement overdue for a revival (along with the rest of that dormant decade’s aesthetic adventures).

Yet the connection between home and personal identity is too ingrained to be limited to adolescent aspiration. It also belongs to more mature frames of mind. In the August 2005 issue of House & Garden, editor Dominique Browning writes of her reluctance to fix a dilapidated summer home because she identifies with its condition: “The problem is I don’t want to renovate the house,” she laments. “I love it exactly the way it is. I know I shouldn’t; this is an immature, fantastical sort of relationship in which I project onto a building my own feelings of being oddly constructed, quietly cantankerous, hard to figure out, and on the downhill slope of physical well-being.”

“Bob, 72, Joan, 70, 42 years (Quogue, NY)” photograph by Mark Robbins, 2003.

Of course, Browning’s empathy with her property is far from unique to our age. In Sex and Real Estate: Why We Love Houses (2000), Marjorie Garber dates the idea of conveying personality through decor to the late nineteenth century, when mass-produced goods became affordable enough to supply the middle class with an ample palette for expression. By the early twentieth century, tastemakers such as the interior designer Elsie de Wolfe and etiquette maven Emily Post were instructing women to think of their domiciles as extensions of themselves. Garber quotes de Wolfe’s admonition of 1913: “A house is a dead-give-away, anyhow, so you should arrange it so that the person who sees your personality in it will be reassured, not disconcerted.”

As the quantities of affordable merchandise soared in the late nineteenth century, so too did the number of publications educating Victorians about how to furnish their homes. The scenario was much like today’s, with presses pumping out shelter magazines and factories pumping out cheap goods. Aimed at women, who took a larger role in managing household affairs as the century progressed, the magazines were true to the era’s moralistic tenor in that they began as guides to good conduct. Gradually, however, they shifted their focus to decor — which is not to say they lost their ethical dimension. For the Victorians, even interior design was freighted with moral significance. Consider the skirts that clothed bare piano legs — “limbs,” as they were delicately called.

With goods and guidance, a woman now had the means to design a home in her own image, but none of this could have been achieved without photography. The development in the 1880s and 1890s of smaller cameras that required shorter exposure times (thanks to electric interior lighting) let homeowners document their design accomplishments. Further, with the introduction of halftone reproduction technology in the early 1880s, images were more easily reproduced in magazines, spreading decorating ideas to a receptive market. As photography opened the Victorian home to wider inspection, the personae encapsulated within its four walls assumed a more deliberate public face. This breach of the threshold between private and social realms helps to account for decorative arts historian Cheryl Robertson’s observation of a growing “professionalism” in attitudes toward home design in the 1880s and 1890s. At that time, Robertson notes, “Women’s magazines and trade literature directed to a female audience had begun to substitute the term homemaking for housekeeping. The shift in vocabulary bespoke a reordering of domesticity from a passive, custodial duty to an active, creative vocation that involved the same decision-making and coordinating talents demanded of office managers and entrepreneurs.”

“Architect: Paddy (Amsterdam),” photograph by Mark Robbins, 2004.

The distinction between house and home — and the very question of what constitutes a household in today’s society — is fundamental to Robbins’s book. The word “household” suggests at least several inhabitants, yet many of the subjects live alone, many are same-sex couples, and only a few are represented as families. In the photographer’s assemblages, home dwellers occupy their own tightly cropped columnar spaces surrounded by other images showing shreds of their environments. Slim margins separate the people from their interiors, building facades, urban settings, and one another — even when they are shown side by side.

Is that discrete white border a margin of privacy? A form of containment? A strip of mortar gluing together the bricks that form an establishment? By atomizing and rebuilding his pictorial edifices, Robbins deconstructs the identities and relationships they represent. House, a rigid carapace, and home, a dynamic constellation of values and tastes, are recombined with a decorator’s attention to pattern and symmetry. The result is a paradox: these stable-seeming assemblages end up as portraits of instability, raising many more mysteries about their subjects than they solve.

“Writer: Kevin, 42 (Cambridge, MA),” photograph by Mark Robbins, 2002.

One way Robbins accomplishes this is by testing our perceptions of public and private. His camera makes conspicuous forays into intimate life: conjugal beds and bathrooms are on display; many individuals are nude or partially undressed. Yet formally posed, facing the camera, these subjects are hardly caught unawares. The body, like the home, is prepared for scrutiny. Clothed and unclothed models alike have the anxious, self-conscious, or forced-insouciant expressions of people awaiting judgment.

These portraits reflect not only how one would like to appear but also who one is when the rest of the world isn’t looking — one’s rituals, vices, and negotiations with lovers and family members. Like the Victorian parlor, they represent in their formality a buffer between real privacy and the world. Even nudity cannot dispel the sense of artifice—many of the bodies are obvious products of exercise regimes, and people are shoeless or shirtless in ways that suggest a compromise with the photographer rather than a habitual mode of comfort.

“American Philosophy: Nancy, 42, Mark, 51, 5 years (Newton Highlands, MA),” photograph by Mark Robbins, 2003.

Flashes of flesh are revealing, but what they illuminate extends beyond physique or decor. For example, in “American Philosophy,” Robbins’s portrait of two college professors in a five-year relationship, a marked difference in levels of self-consciousness suggests other tensions. The subjects, posed outside Nancy’s shingled New England cottage, flank the interior like pendants in an altarpiece. Nancy wears a zippered jacket, but not for warmth, apparently, because her toes are bare. She looks nervously at the camera from under a curtain of hair, her hands folded protectively over her stomach. Mark is shirtless and gazes off to the side. The verdant setting, her shame, and his skin, not to mention the composition’s medieval echoes, connect this image to the Fall. In place of a serpent disrupting Edenic harmony, however, is a living room revealing polarized tastes. Austere Mission-style furniture and a sisal rug cohabit with an Art Deco wing chair and pleated, swagged draperies. Does this photo of clashing yet integrated styles unite the couple or push them apart? Does Mark look at Nancy in complicity, his gaze cutting through the central image? Or does he look away from the lens, self-absorbed? The photographer creates the mystery.

Robbins’s placement of images is suggestive in many ways. His compositional houses sometimes reflect the organization of real ones (an arrangement that, as children recognize, is anthropomorphic, with upper windows taking the place of eyes, kitchens of bellies, and basements of bowels). In a portrait of his own parents at home, Robbins put the cellar at the bottom of the montage, details of gables at the top, and the living room and kitchen in the middle. But where many homes grow more chaotic on the lower floors, this one demonstrates a fight against entropy at every level. Even with its raw pipes and wires, the basement is a model of rationality.

“ABA: Jonathan and Christopher (East Hampton, NY),” photograph by Mark Robbins, 2003.

Robbins also exploits classical symmetry as a feature of both photos and layouts. Typical is “ABA,” his portrait of Jonathan and Christopher in their summer home. A bedroom ceiling fan marks the midpoint of the suite. Extending outward on either side are pairs of pillows, windows, and end tables. Next comes a pair of Christopher pictures, then a pair of garden-hedge pictures, and finally a pair of Jonathan pictures. Yet the symmetry is disrupted in both obvious and subtle ways. Christopher holds his tennis racket in two different positions, suggesting a narrative sequence or even a filmstrip. The hedges, however, are identical; they create a strong horizontal rhythm that contrasts with the vertical poses. (Such rhythms, reminiscent of the syncopated patterns of building facades, run throughout Households.) The portraits of Jonathan are also identical, but one is flopped to form a mirror image. Whereas his partner is animated, his own stance is static, at the periphery.

In the Households’ images, matching furniture pieces resemble old couples that dress alike. Family members rhythmically posed in doorways take on the formality of caryatids carved into a building’s facade. In the interiors, Robbins reveals a particular interest in collections. A wall is arrayed with ethnic masks in one image; shelves are stuffed with political memorabilia in another. These groups evidence a concentrated form of the homeowner’s effort to project identity — a quest to complete and thereby perfect a representation of the self. “Because a collection results from purposeful acquisition and retention, it announces identity with far greater clarity and certainty than other owned objects,” note business academicians Russell W. Belk and Melanie Wallendorf. Yet these microcosms of self-definition are also fragments of roomscapes that are in turn assimilated into the larger structure of Robbins’s compositions. The viewer is continually reminded that all this cultivation of objects and arrangements is devoted to public perception, mediated through Robbins’s lens. Even the most ardent efforts to control appearances slip away from the collector and collide with the photographer’s view. Through the very gesture of assemblage, Robbins presents himself, not as a casual observer of people’s homes and lives, but as equal partner in the art of contrivance. By the end of Households, we must ask ourselves, whose collection are we looking at anyway?

“Chris, 33 (Columbus, OH),” photograph by Mark Robbins, 2003.

Like any collector, Robbins is driven to encapsulate — but with boundaries that are rewardingly open-ended. Constructed of beamlike panoramas and columnlike figures, his photos represent an edifice that is also anatomy, a bionic merger of nature and art. The skeletal rigor of architecture combined with the emotional nuances of decor mirrors the duality of body and mind. Ultimately these households register stability and flexibility, an expression of coherence and an erasable slate, a window for voyeurs and a mirror for self-reflection. Even the most modest among them is a mansion with many rooms.

Julie Lasky is the editor-in-chief of I.D., the international design magazine. A former editor of Interiors magazine and managing editor of Print, she is the author of the book Some People Can’t Surf: The Graphic Design of Art Chantry.

This essay is adapted from Mark Robbins’ Households, published by The Monacelli Press (June 2006). It is reprinted here courtesy of the author and the publisher.

Mark Robbins is the dean of the School of Architecture at Syracuse University. Before coming to Syracuse in 2004, Robbins was the Director of Design at the National Endowment for the Arts in Washington DC where he developed an aggressive program to strengthen the presence of innovative design in the public realm. Among his many awards is the Rome Prize from the American Academy in Rome.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Julie Lasky

Related Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

Recent Posts

Candace Parker & Michael C. Bush on Purpose, Leadership and Meeting the MomentCourtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging Why scaling back on equity is more than risky — it’s economically irresponsibleRelated Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

Julie Lasky is editor of Change Observer. She was previously editor-in-chief of

Julie Lasky is editor of Change Observer. She was previously editor-in-chief of