Printed Matter Inc. was founded, in New York City, in response to a lack. Before 1976, few resources were available to support the printing of artists’ books. This was partly intentional: many flexible, low-cost artists’ books sought to critique the dominant institutional and commercial structures of the art world. At the same time, a lack of financial and organizational support limited their ability to reach audiences outside of the market’s typical territories. In 1976, a group of nine artists and art workers formed Printed Matter to change these “satisfying but hardly self-supporting” conditions of production.

“When we began our distribution service, no one––including ourselves––realized just how broad the scope and vitality of the field was,” they wrote in a founding statement of purpose. “Only a unified effort, drawing artists’ books from all available sources and placing them in a comprehensive network of outlets, can fulfill the potential that artists’ books represent.” To this end they offered distribution, circulation, and printing services to support artists who were engaging with the book as a medium. In time, this effort expanded to include exhibitions, education, book fairs, an online archive, a prone-to-move retail bookstore, and audiences outside of art capitals and museum circuits.

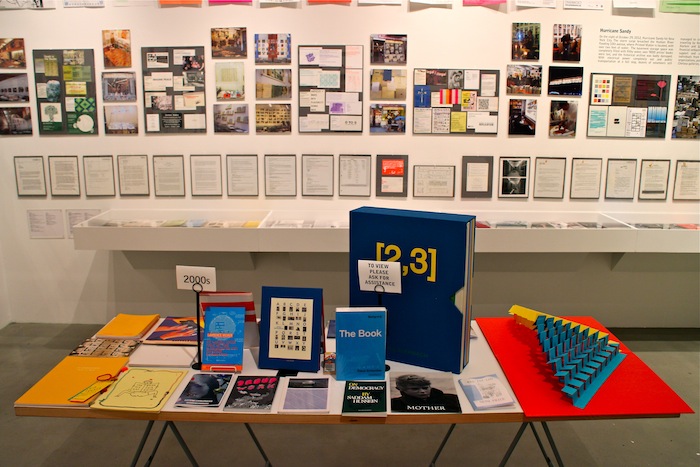

Learn to Read Art: A Surviving History of Printed Matter, currently on view at New York University’s 80WSE gallery, charts the organization’s evolution from its founding to the present. Displaying administrative paperwork, ephemera, and published projects, the exhibition makes visible the labor that went into the process of disseminating artist’s books. What emerges is a curated selection, one imagines just the tip of the iceberg, of the heroic feats of organization, petitions, and IRS acrobatics, necessary to maintaining the day-to-day operations of an art catalogue distribution service. Printing, the exhibition teaches, is always an uphill bureaucratic battle, before it is an art. To narrate its history necessitates not only showing off its fruits but also archiving the often tedious roots.

Among charts of gross book sales and handwritten organizational flowcharts, an early memo on the budget shows the fiscal calculations undertaken to make ends meet. Under Salaries & Duties, “$25,000 for 5–6 part-time people” is crossed out, replaced by “$15,000 for part-time/freelance work.” While Printed Matter originally intended to turn a profit, it soon realized that the costs of printing small runs of artists’ books were too high and so the group applied, and appealed, for non-profit status.

“We are the sellers but we are not in business,” they explained in their petition for non-profit status, noting that all surplus funds go towards further printing. Although visitors may “purchase” (scare-quotes theirs) materials while visiting the store, its primary intention is to serve, like its books, as a site for meeting and learning, as books are distributed without regard to their profit. In fact, Printed Matter stopped printing altogether, devoting itself full-time to distribution and cataloguing until 2003 when its program was revived.

For those bored by these pecuniary concerns, there are other pleasures of the archive: photos of the stores’ window displays, covers and designs of their printed catalogues, and limited edition artists works. Many of the original twelve books published between 1976 and 1978 are on display, including two by experimental novelist Kathy Acker. Across the headline of a saved newspaper article announcing the opening of Printed Matter’s bookstore, a note scrawled in red ink reads: “Please put me on your mailing list. My one claim to fame in your department is giving Robert Smithson fifty dollars, in 1956, to do a woodblock cover for my little magazine,

PAN. Mimi Gross did one, too.” But while Smithson’s prices increased, the show also reminds us that other aspects of the art market have little changed since. Guerilla Girls posters from the ’70s, calling out curators and critics for their reification of male supremacy, are as apt now as then.

Or consider Printed Matter’s lengthy letter of appeal to the IRS, which reads like a timeless defense of art’s egalitarian ideals:

“Throughout history books have played a major part in the dreams of humankind. They are the world of ideas. Artists’ Books are art because that’s what artists make but they are more than that. Artists’ Books take art and ideas into places where there are not other facilities for the housing of these ideas. They are direct communication between artist and audience and they make it possible for the ideas in art to exist in the hands of all people …We believe it would be a great loss to our national culture if the ideas and values inherent in contemporary art were not available to everyone.”

Amen.