June 29, 2012

The Shape of Lunch

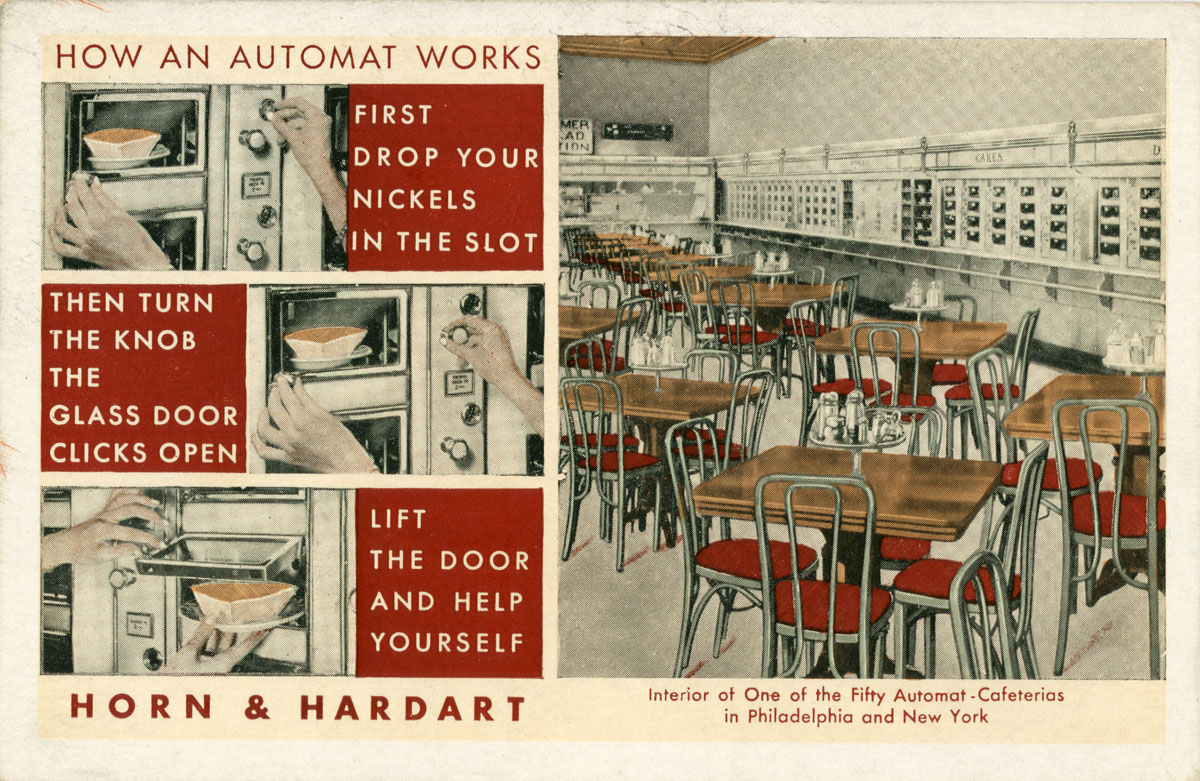

“How An Automat Works” postcard, for sale at the NYPL shop (via Brightbill Postcard Collection)

“How An Automat Works” postcard, for sale at the NYPL shop (via Brightbill Postcard Collection)

In the late 1990s, when I was working in midtown, I became obsessed with a new sandwich shop on Madison Avenue called Sandbox. Everything at Sandbox was pre-made, presented in bright cases in tidy plastic packages that somehow made the food look fresh rather than stale. The neatly stacked ingredients gave these sandwiches the appeal of an everyday tea party, and made sloppy subs and schmeary bagels unappealing. It was lunch as an industrial design product, as if Dieter Rams were let loose in a deli. A story in the New York Daily News on this so-called phenomenon had the headline “The Layered Look Is Back.”

It was an idea both ahead of and behind the times. Pret A Manger has franchised the fresh, boxed sandwich all over the world; Sandbox disappeared quickly. But as I discovered at the New York Public Library’s delightful new exhibit, “Lunch Hour NYC,” Sandbox’s theory that the sandwich needed a better package was an old one, wrapped up (ha!) in the original definition of lunch as a meal eaten out, eaten quickly, and eaten with one hand.

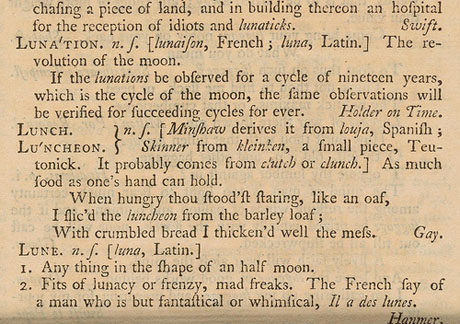

“Lunch” entry in A Dictionary of the English Language, Samuel Johnson, London: J. and P. Knapton; J. and T. Longman, 1755. NYPL, Rare Book Division.

The exhibition, which runs through February 2013, draws on the library’s collection of menus, dictionaries, cookbooks and ephemera, and even includes a working Automat (the shelves are filled with recipe cards, not pie). But the most important artifact may be Samuel Johnson’s 1755 definition of lunch as “As much food as one’s hand can hold.” What fits in the hand? An apple. An oyster. A slice of bread. Embedded in Johnson’s definition of the meal’s size, and in the rise of lunch hour as part of the urban work day, is the idea of the pacakge. Lunch is the ultimate square meal, an industrial product from its inception, just like the punch card.

There is the sandwich, of course, eaten at home by women and children, or out by the working man. Nicola Twilley interviewed the exhibition’s curators, culinary historian Laura Shapiro and Culinary Collections Librarian Rebecca Federman for Edible Geography, and they had some interesting things to say about its not-so-humble origins.

Laura Shapiro: Sliced wrapped bread first appeared in 1930, and that became the sandwich standard right away. They had the slicing technology before then, but they didn’t have the wrapping technology and the two had to go together.

Before sliced bread, the lunch literature is full of advice on social distinctions and the thickness of bread in sandwiches. You slice it very thick and you leave the crusts on if you’re giving them to workers, but for ladies, it should be extremely, extremely thin. Women’s magazines actually published directions on how to get your bread slices thin enough for a ladies lunch. You butter the cut side of the loaf first, and then slice as close to the butter as you possibly can.

Metal lunchboxes from the 1950s line the wall in this section of the exhibition. Photograph by Jonathan Blanc for the New York Public Library.

Peanut butter was even once a refined choice, made fresh and combined, for spreadability, with cream or chili sauce. “A Date With A Sandwich,” a Best Foods cookbook from the 1950s, suggests strawberry/cottage cheese, tongue/pickle and peanut butter and raisin as ingredients. A section of the exhibit on lunch counters includes a wall of behind-the-counter slang, in which the different bread types are prominently featured. “One on a pillow” is a hamburger. “On a raft” is on toast. A step further in the integration of meat and edible wrapper is the hand pie, from calzone to empanadas, samosas to knish.

Unless you were eating right at the counter, those square, rectangular and wedge-shaped packages of protein and starch tend to need another protective package made of glassine, cardboard or metal. Any child of the 1970s will swoon at the NYPL’s wall of commemorative lunchboxes, and covet more than one. Pac Man and Annie, Superman and Campus Queen, Care Bears and Charlie’s Angels. I wanted them all, even the shows I wasn’t allowed to watch.

The metal lunchboxes for kids had their origin in box lunches sold on site to working men. The exhibition has the sheet music for the song “Who WIll Buy a Box Lunch?” forever immortalized by Minnie Mouse. In the 1933 Disney short “Building a Building,” Minnie delivers lunches to a construction site, skipping along the girders. Predictable mayhem ensues.

It is too bad the library’s collections don’t include artifacts from the latest iteration of the packaging and repackaging of lunch food, the bento box, the craze among design-oriented mothers who believe that a cute lunch is an eaten lunch. There is an interesting section on the origins and vagaries of school lunch, complete with cafeteria trays and a number of other elements that make this an interesting exhibit to visit with an older child.

The most dramatic and architectural squaring-up of lunch is, of course, the Automat. “Lunch Hour” devotes a bay to a loving anatomization of the Horn & Hardart restaurants that were once so ubiquitous in New York City. The first opened in July 1912 in the middle of Times Square.

“Automat, New York,” Berenice Abbott, 1936. NYPL, Photography Collection.

Shapiro: Every Horn & Hardart location had a manager’s book, with the rules for doing every single thing — how to squeeze the orange juice, how much filling to put on each sandwich, how to treat your customers, and how often to throw out the coffee. All the food came from a central commissary, which was a block-large building on 50th Street, between 10th and 11th. They did nearly everything there, for economy of scale and for quality control, and then they had extremely precise instructions for anything that had to be made in store. The idea was that any Automat you went to, you would get precisely the same dish.

Federman: And you never saw the people preparing your food, which somehow made it seem more sanitary, as if strangers weren’t touching your lunch. In the exhibition, we show the mechanics, so you can peek backstage and see how it worked.

The Automat replaced the box, and sometimes even the bread, with a brass-trimmed door, presenting each part of the meal in a space both glamorous and utilitarian. I think there’s a connection between what I loved about Sandbox — its tidiness, its regularity, its immaculate presentation — and the qualities people liked in an automat. They perfected a formula (those recipe books describe egg salad down to the last chopped teaspoon) and as long as they kept it clean and high-quality, they prospered. Once upon a time, industrialized food was a safe harbor. And lunch wouldn’t be lunch without the clock.

As a final note, given the ongoing controversy about the NYPL’s expansion and renovation plans: this exhibition is exactly the right blend of scholarly and populist, and shows those two goals not necessarily to be at odds.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Alexandra Lange

Related Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

Recent Posts

Candace Parker & Michael C. Bush on Purpose, Leadership and Meeting the MomentCourtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging Why scaling back on equity is more than risky — it’s economically irresponsibleRelated Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

Alexandra Lange is an architecture critic and author, and the 2025 Pulitzer Prize winner for Criticism, awarded for her work as a contributing writer for Bloomberg CityLab. She is currently the architecture critic for Curbed and has written extensively for Design Observer, Architect, New York Magazine, and The New York Times. Lange holds a PhD in 20th-century architecture history from New York University. Her writing often explores the intersection of architecture, urban planning, and design, with a focus on how the built environment shapes everyday life. She is also a recipient of the Steven Heller Prize for Cultural Commentary from AIGA, an honor she shares with Design Observer’s Editor-in-Chief,

Alexandra Lange is an architecture critic and author, and the 2025 Pulitzer Prize winner for Criticism, awarded for her work as a contributing writer for Bloomberg CityLab. She is currently the architecture critic for Curbed and has written extensively for Design Observer, Architect, New York Magazine, and The New York Times. Lange holds a PhD in 20th-century architecture history from New York University. Her writing often explores the intersection of architecture, urban planning, and design, with a focus on how the built environment shapes everyday life. She is also a recipient of the Steven Heller Prize for Cultural Commentary from AIGA, an honor she shares with Design Observer’s Editor-in-Chief,