December 31, 2009

The Shape of Now

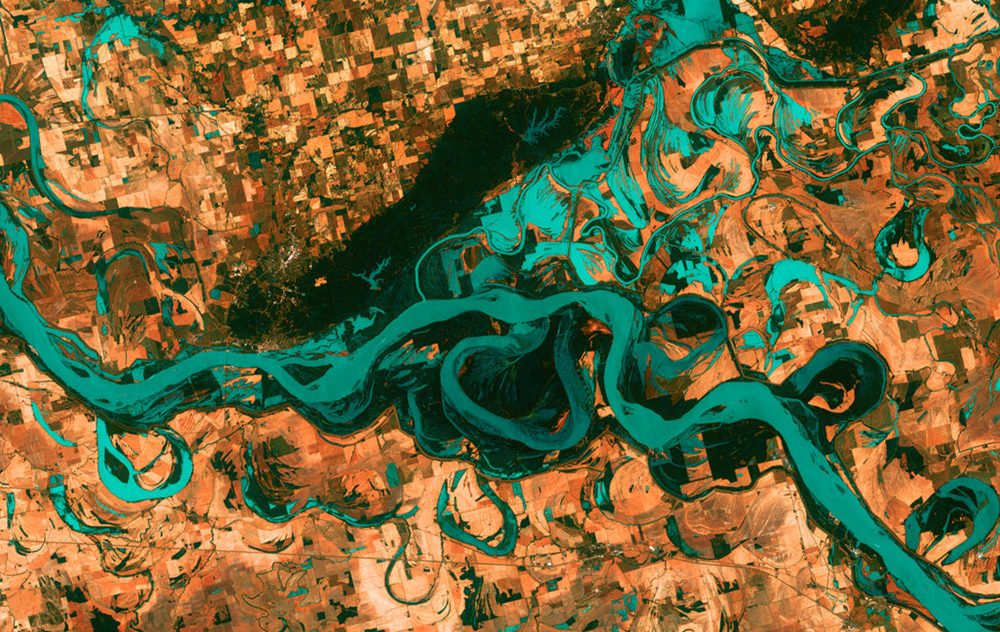

USGS/NASA/Landsat 7

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published as a letter to attendees of AIGA’s 2016 National Design Conference. It is republished here with a renewed sense of relevance.

In 1968 my father graduated from St. Andrews University in Scotland with a degree in geography. Following that, he moved to Canada and earned a master’s degree in geomorphology. Geomorphologists study why landscapes look the way they do. They try to decode the history and dynamics of those landscapes to predict how they may change. If you remember from grade school that rivers cause erosion or that they transport sediment, then you’ve had an introduction to fluvial geomorphology.

As a kid, I loved visiting my father’s office. It had wheeled chairs and a high drafting table covered with technical pens and mysterious looking mechanical tools. He used these tools to draw maps. Like design of that day, cartography was a craft. Sometimes I’d go with him on field surveys—which is how geographic information was collected back then—bouncing along in the back of a blue VW bus with a half dozen students and no seat belts. The work he did was mostly used for coastal conservation and wetlands restoration, but it had some commercial applications as well. That was the first 10 years of his career.

During the next ten years, advances in technology made manual cartography almost obsolete. GPS technology meant surveying could be done from satellites instead of Volkswagens. Maps could be rendered with CAD rather than ruling pens. The shape of his profession morphed dramatically. Computer based Geographic Information Systems could capture, analyze, and present geometrically more data than a person could. And so the value of rendering geographical information was replaced by interpreting it.

In the subsequent ten years my father’s job transformed from trudging through marshes in rural Nova Scotia to using remote sensing to analyze evapotranspiration in Australia. Data like that was used to inform agricultural policy and mitigate drought. His last project before retiring was working with the World Bank and a coalition of foreign governments to detect and remove land mines in Cambodia so land ownership records—destroyed by the Khmer Rouge—could be reestablished.

The world and career you inherit today may bear little resemblance to the one you’ll inhabit tomorrow. Sitting at his drafting table, smoothly inking a contour line, my father could not have imagined that line leading to a role in rebuilding a southeast Asian economy.

Somewhere there is a community of diehard cartographers preserving their craft and drawing maps by hand. That’s important. They got into geography because they loved the making part of it. Elsewhere, the diaspora of former geographers unable or unwilling to adapt to the changing nature of their profession have forged new careers entirely. That’s important also. They loved thinking like geographers, and now they apply that thinking to other pursuits. My father was always interested in how geography effected people. He adapted to the changes in his field in ways that brought him closer to that interest.

If you’re a designer, this story probably sounds familiar. Every day it seems a new technology is threatening a beloved craft. Every year a new framework for “design” seems to draw more people into its definition, and edge more people to its margins. The same is probably true for all professions—not to mention politics or the world. Like a geological force, the pressure to conform to the changing shape of now is relentless. Our options for responding to that pressure are equally constant: retreat, resist, or adapt.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Christopher Simmons

Related Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

Recent Posts

Minefields and maternity leave: why I fight a system that shuts out women and caregivers Candace Parker & Michael C. Bush on Purpose, Leadership and Meeting the MomentCourtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packagingRelated Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays