August 25, 2011

Thoughts From the Coal Face

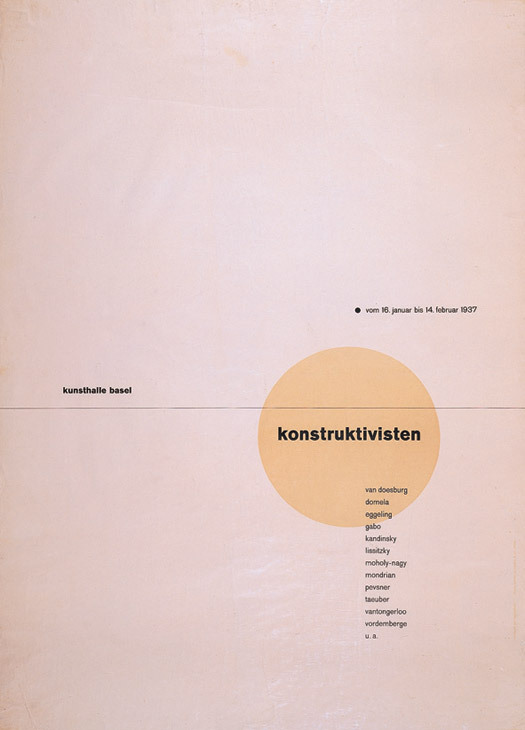

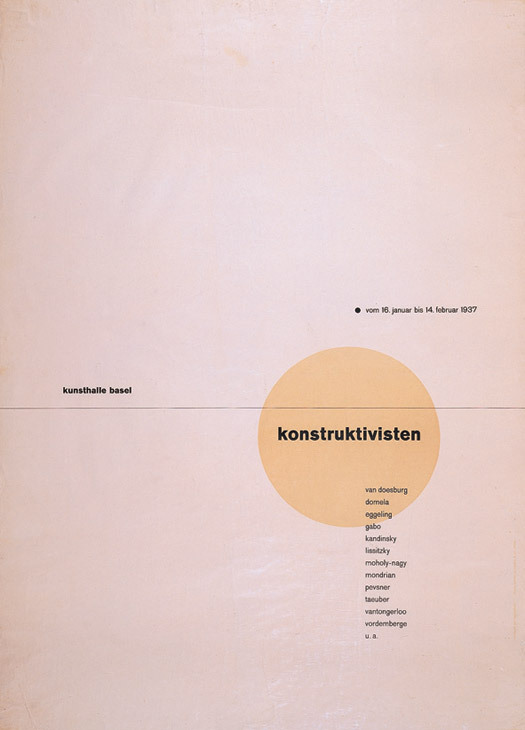

Konstruktivisten, designed by Jan Tschichold for an exhibition in Basel, Switzerland, in 1937

Having just spent several years hacking away at the coal face of graphic design history in order to write a comprehensive history of graphic design (The Story of Graphic Design, New York: Abrams, and London: The British Library, 2010), I wanted to reflect on some of the issues Rick Poynor raised in his characteristically clear and thoughtful essay on the current status of graphic design history “Out of the Studio: Graphic Design History and Visual Studies.”

A Problem Child

One of Poynor’s central points was that graphic design history has yet to establish itself within the family of academic liberal arts disciplines. Like a bastard child born to some pious Victorian household, it has been shunned by most art historians. Those that have shown an interest in the subject have tended, nevertheless, not to give it the close care and attention it deserves. To date, it has spent most of its young life in the studios of those graphic designers that have had a sufficient interest in the historical roots of their practice.

Clearly, if graphic design history is to thrive as an academic discipline, it needs to find a more secure and well-appointed home. But to do this successfully, it is necessary first to identify why this kind of history has been considered to be such a problem child.

Poynor touched on some of the reasons in his essay, but there are two important groups of reasons which were not mentioned there (this is not to criticize an essay whose thrust had a different slant). Those in the first group are more or less self-evident, those in the second less so, but both of them are fundamental and each needs to be made explicit.

Group 1: Complexity, Art Status and Ephemera

The first group of reasons why graphic design history has not become sufficiently established is rooted in the nature of the subject itself. Graphic design is inherently complex. It is also fundamentally utilitarian, being more a carrier of messages than a mode of artistic expression. And then, of course, most graphic design is ephemeral. All of these fundamental traits have helped to dissuade historians from engaging with it more fully.

One of the complexities of graphic design comes from the fact that it is essentially a reproductive medium. A design only really begins its life after the designer’s “artwork” has been reproduced in multiple copies and put in front of its audience. (The Printed Picture by Richard Benson describes many of the reproductive processes brilliantly.) These processes — printing, binding, web design, etc. — usually involve machinery or software that have to be operated by specialists: printers, binders, web technicians and the like. It is, therefore, also a collaborative endeavor, which can add a further layer of complexity.

There is complexity too in the sheer variety of objects that are touched by the process of graphic design: books, magazines, posters, labels, packaging, signage, websites, and on and on. The range of objects under its purview is vast, and with every innovation in information technology the range only increases.

A further form of complexity lies in the many tasks that any class of graphic design object is asked to perform. One need only think of the different tasks given to the book format. Maps, novels, children’s stories, scientific text books, law reports, religious texts, instruction manuals and so forth; each bring with them their own set of design requirements. They all look different because they have to be read slightly differently, and then, often, by quite different audiences.

It is perhaps unsurprising that this inherent complexity, or lack of clarity, should be carried over into the very title “graphic design”. Most descriptive terms, such as “policeman,” “artist” or, even closer to home, “poster designer,” plant a concrete picture in one’s mind. But “graphic designer” doesn’t. There is no core activity to which it can be linked. (I’ve long got used to the look of puzzlement, mild panic or complete vacuity that often masks the face of anyone who has asked me what I do for a living.) Finding a better title is not easy, though. Similarly Latinate terms, such as “visual communicator” or the like, don’t help very much.

The difficulties posed by these kinds of complexity are then compounded by graphic design’s uncertain art status. This stems partly from the fact that a work of graphic design exists in multiple copies rather than as a single, unique object. Whereas fine artists are usually successful if they make a single object that is highly prized, graphic designers base much of their success on the number of times an image has been reproduced.

Adding to its uncertain status is graphic design’s role as a service provider. However much artistic skill has been brought to a particular design, the design always has a job of work to do. It is either selling or informing, or doing a bit of both, so it tends to be looked on more as a functional object than an artistic one.

Both of these reasons are connected to a third reason: the very ephemeral nature of most graphic design. Are posters really meant to be hung in galleries long after the events they promoted have passed? Is there really any social value in keeping beer mats or luggage labels?

All of these areas of uncertain status and complexity make graphic design difficult to write about, but they are also what make it so interesting, both as a practice and as a subject of study. The very quotidian nature of so much graphic design causes it to be marked with the minutiae of the times in which it is made. Names, dates, places and any number of other tell-tale signs lend it a degree of specificity that is rarely matched by any other kind of cultural artefact. For this reason alone (and there are other compelling aesthetic reasons too), graphic design ought to be especially attractive to historians.

Group 2: Looking Closer (at the Design itself)

The second group of reasons why graphic design history has not established itself more broadly has to do with the kind of history that has been written so far. “Most histories have focused on the social forces that prompted particular kinds of graphic design, or else on the influence of new technologies, or the swell of ideas that surrounded a particular group of designers or artists. All these approaches are valid, but they can only explain the appearance of a piece of work in a general way. Unlike in the fine arts, where the formal properties of artworks are scrutinized and discussed at length, there has been little graphic design history that tries to pin down what the salient features of a particular design are and then explain, with something more than generalizations, why they look the way they do. The impression given is that it is more important to understand the concerns that surrounded the creation of a design than the design itself.” [1]

It is surprising just how rare a detailed analysis of the formal characteristics of a work of graphic design really is, especially when we know just how compelling picture-related descriptions can be (it is why they dominate our news media, for example) and then also how they are inherently more memorable by being tied to an image. A short example of this kind of analysis can be given, say, for Jan Tschichold’s beautifully sparse “Konstruktivisten” poster (see above), which he designed for an exhibition in Basel, Switzerland, in 1937:

“a study in contrasting pairs: the pair of rectangles, large and small,

created by a thin bisecting horizontal line; the pair of circles, large

[orangey] grey and tiny black above; the pair of arrangements of small

light text, a single line above and a thin column below; and, lastly,

the pair of lines of bold text in contrasting sizes. None of them

derived their character from any over arching rationale, there is

no apparent formula guiding their placement, and yet the tension

generated between them and, also, between them and the edges

of the poster, creates a dynamic harmony that reverberates throughout.” [2]

On its own, clearly, this picture-related analysis is not going to set the world of graphic design turning on a new axis. But, the concept of a series of contrasting pairs does allow the reader to see Tschichold’s poster in a new and more concrete way. Moreover, the concept can be taken and applied elsewhere. Teachers could use it as a simple exercise for students (‘create a design out of a series of contrasting pairs’), and designers could use it as a starting point for a job they were working on.

The Paradox of Introspection

“Most designs are the result of a long and considered process of experimentation and refinement. Graphic designers often make adjustments involving the tiniest margins, matters of millimetres or fractions of inches. To get some idea of the concerns behind any final form, therefore, it is necessary to look at the design in some detail. By looking closely at a design it is possible to enter into the work, and from this more intimate vantage point one can gain a greater understanding both of the work itself and of the subject as a whole.” [3]

The process of looking inward to see more of what lies outside is one of the paradoxes of introspection. Like the physicist who studies the smallest parts of atoms in order to learn about the universe as a whole, so looking closely at the formal aspects of particular works can reveal many general, yet fundamental, aspects of graphic design. It has allowed me, for example, to touch on the origin and use of the word ‘style’ in art; to seek an explanation for the prominence of the colour red in all forms of graphic communication; to engage with aspects of perceptual psychology when considering the legibility of letters; to consider the nature of superstition when looking at the use of photographs by the news media; or to question the nature of identity in a consumerist society when confronted with relatively recent works of graphic design-related art. These are just some of the important issues (which, in Poynor’s essay, Jonathan Baldwin calls “history-less history”) that have rarely, if ever, found their way into previous graphic design histories.

The success of this kind of specific, object-centred approach has been reaffirmed relatively recently, in the UK at least, by a BBC radio series called A History of the World in 100 Objects, and by its subsequent best-selling book (both written by Neil MacGregor, the director of The British Museum). In bringing a general audience closer to the world of art and design, it follows in a long line of similarly object-specific programs and publications.

To champion this approach is not to promote it as the only way of writing graphic design history. Indeed, the discipline as a whole, benefits from having a wide range of approaches. Another one, mentioned by Poynor in his essay, which was advocated by Guy Julier and Viviana Narotzky, is for “design history to return to its roots and bed itself with practice” [4]. There certainly is value in bringing together history and practice, but, as Poynor commented, if that is all that is done the subject will not thrive.

A plurality of readers needs to be fed by a plurality of historians. Again, with reference to Poynor’s essay, I do not believe that graphic designers are unable to be objective enough to write good histories, as the early “historian-cum-practitioner”, Louis Danziger, has written [5]; his implication being that the task should be the preserve of historians. The British typographer, Harry Carter (1901-1982), for example, wrote several sufficiently objective histories [6]. And a telling comparison can be made between him and his near contemporary, friend and co-author, Stanley Morison (1889-1967), a bona fide historian (and only an occasional, rather poor, practitioner). Unlike Carter though, Morison’s many prejudices shine through in his writing [7], which should come as no surprise since, like most other historians of art or design, Morison had looked long enough at works of art or design to develop some strong preferences.

A Narrative for Everyman

All readers of history, be they academics, practitioners or general readers, benefit from having a text that is clearly written and coherently structured. Previous comprehensive graphic design histories have adopted a loose structure in which the focus of the writing shifts variously between individuals, countries, technologies and styles of design. This is not necessarily a bad thing, but it does make it hard for readers to hold on to the meaning of the text. The sense of any text is more easily grasped when it is hung on a conceptual framework, and not just guided by a basic chronology. (With this in mind, the organizing principle behind The Story of Graphic Design was the evolution of graphic styles in the West, with each chapter describing one of the main styles of graphic design.)

As well as a clear structure, it is important that the text is written clearly, both linguistically and conceptually, especially when the text is likely or, indeed, intended to be read by people who are new to the subject (a group not much in the mind of some writers of graphic design history). Accordingly, a simple narrative was used in The Story of Graphic Design to describe each style of design and the links that exist between them. The importance placed on a clear and engaging narrative was alluded to by the book’s title; ‘The Story of …’ having become a well-established device for narrative histories of art.

(One reviewer questioned whether an attempt was being made to “fool” the reader by using the word ‘story’ in the title rather than ‘history’. But like other similarly titled histories, the inspiration for the title came from Ernst Gombrich’s The Story of Art, perhaps the world’s best-selling history-of-art book. It has been in print for over half a century and sold over seven million copies.)

The special emphasis placed on the narrative flow of the text made it important not to break up the text with sub-headings (the close proximity of images to their accompanying texts allowed each image to serve as a kind of visual sub-heading). And by keeping the captions short, there was no doubt about where the reader’s focus should lie. Throughout, the onus was on encouraging readers to dive into the main text. They might wish to do so either to find out about a particular image, or to digest the text chapter by chapter, each of which were written as relatively self-contained stories.

The Benefit of Hindsight

A requirement of all history books, not just those on graphic design, is that they fill in the gaps or correct any factual errors contained in previous histories. (No one has done more to point out the errors and omissions in recent graphic design histories than the US historian and graphic designer, Paul Shaw, in his suggestively named blog Blue Pencil, which is now part of his more general blog.)

Among the most surprising omissions from previous comprehensive histories of graphic design is the lack of any definition of the subject. Admittedly, it is difficult to provide a precise definition for something that is so inherently varied and complex. Graphic design is fuzzy at its edges. Exactly what is illustration or fine art, say, rather than graphic design, is sometimes hard to decide. But rather like pornography, you tend to know what it is when you see it. So it is odd, then, that the only real attempt at a definition is to be found in a concise history, Richard Hollis’s Graphic Design: A Concise History (London: Thames & Hudson, 1994), though here the definition is of the most general kind: “Graphic design is the business of making or choosing marks and arranging them on a surface to convey an idea” [8]. The same could be said for oil painting. (The definition provided in The Story of Graphic Design, by contrast, revolves around a “holy trinity of essential characteristics: words and pictures, two dimensions, and reproduction”. [9])

And there are other surprising omissions too. For example, the Coca-Cola logo, which, as one of the best-known pieces of graphic design, has a special status in the West. Its extraordinary familiarity can tells us a lot about graphic design (e.g. the union of script and sound, how we read illegible logos, the importance of the colour red, etc.). And yet, no mention of the logo is made in any of the comprehensive graphic design histories — though again, Hollis’s concise history does include a picture of it. (A short analysis of the logo is included in The Story of Graphic Design [10], and a longer one can be found in the recent Italian text, ‘Sussidiario: Grafica e caratteri moderni’ by Sergio Polano and Paolo Tassinari (Milano: Electaarchitettura, 2010).)

There are also occasions when significant works have appeared in histories, yet much of what makes them important has been left out. The famous portrait of Che Guevara is another work that has a special status. It is one of the few works that has a currency outside the world of graphic design (logos excepted). More than this though, it has a good claim to be the world’s most well-known portrait (as well as being popular in the West, it still has a resonance in Latin America and many previous communist countries). Even the world’s most popular religion, Christianity, which has a history of portraiture that stretches back to the first centuries AD, has not produced anything that could claim to be so well known. This is an extraordinary achievement for graphic design, and one that should be recognized, or celebrated even, in its history. However, no comprehensive history has done so. (A full analysis of the image is included in The Story of Graphic Design [11], though a more complete study can be found in Che Guevara: Revolutionary & Icon, ed. Trisha Ziff (London: V&A Publications, 2006) and then also in Che Guevara: Icon, Myth and Message by David Kunzle (Los Angeles: Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 2002).)

An example of a factual error that needed to be corrected by a new history can be found in the writings on the origins of one of graphic design’s most popular symbols, the peace logo. Again, few histories have mentioned this significant symbol. Those that have invariably describe it as having been made for the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND). Other kinds of graphic design writing also do this, and some have even described its design as having been influenced by the British philosopher and political activist Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) [12]. However, Russell’s own letters and the archive material from the logo’s British designer, Gerald Holtom (1914-1985), seem not to support either description [13]. Both sources point to the logo’s creation as being for a protest march organized in 1958 by a pioneering but shortlived British pacifist group, the Direct Action Committee Against Nuclear War (or DAC), who in some ways were rivals of CND. This origin has been confirmed with me by Dr. Michael Randle, one of the organizers of the march and a former chairman of DAC. Interestingly, Holtom describes in one of his own letters how he had offered to design a symbol for CND free of charge but they turned him down.

Any book that aims to describe the broad sweep of a subject has to confront the difficulty of deciding how much detail to include. Things will be left out that some readers consider to be essential and, conversely, other things will be included that are thought to be superfluous. No doubt, I have sinned on both fronts. But those histories that avoid the same mistakes I have made will render these sins less grievous. And if some of these histories can also excite a greater interest in the subject, among all kinds of readers, then it will be more likely that graphic design history can find a secure and nurturing home for itself.

Notes

1. p.13, ‘The Story of Graphic Design’ by Patrick Cramsie (New York: Abrams, and London: The British Library, 2010).

2. p.203, ibid.

3. p.14, ibid.

4. ‘The Redundancy of Design History’ by Guy Julier and Viviana Narotzky (Leeds Metropolitan University, 1998).

5. p.333, ‘A Danziger Syllabus’, Graphic Design History, ed. Steven Heller and Georgette Ballance (New York: Allworth Press, 2001).

6. Among Harry Carter’s most notable publications are: ‘Fournier on Typefounding’ (London: Soncino Press, 1930); ‘John Fell’ with Stanley Morison (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1967); ‘A View of Early Typography Up to About 1600’ (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969); ‘A History of the Oxford University Press’ (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975).

7. Morison’s most self-effacing prejudice was against the font whose creation he had masterminded, Times New Roman. Soon after its completion he described it as “hardly a book type – for it is strictly appointed for use in short lines …”, p. 134, ‘Letters of Credit’, Walter Tracy (London: Gordon Fraser, 1986). Times has been one of the most popular book faces of the last 70 years.

8. p.7, ‘Graphic Design: A Concise History’ by Richard Hollis (London: Thames & Hudson, 1994).

9. p.11, id.

10. pp.13-14, & pp. 154-155, ibid.

11. pp.272-277, ibid.

12. ‘The Magic of the Peace Symbol’ by Steven Heller (Observatory, www.designobserver.com, 03.24.08), and pp. 18-20, ‘The Peace Symbol’, Design Literacy (Continued) by Steven Heller (New York: Allworth Press, 1999).

13. On 15 April 1962 Bertrand Russell responded to a letter he had received from Mr. H. Pickles, the editor of a German publisher, Lichthort Verlag, who had argued that because the arms of the peace symbol pointed downwards it was actually a death symbol. Russell replied: “I am afraid that I cannot follow your argument that the ND badge is a death-symbol. It was invented by a member of our movement as the badge of the Direct Action Committee against Nuclear War, for the first Aldermaston March. It was designed from the naval code of semaphore, and the symbol represents the code letters for ND. To the best of my knowledge, the Navy does not employ signalers who work upside down.” Gerald Holtom’s archive is held in the Commonwealth Collection at the University of Bradford, UK. For online information about the design of the peace logo see the short paper ‘The Origin of the Nuclear Disarmament/Peace Symbol’ by Andrew Rigby, Coventry University, UK, 2008.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Patrick Cramsie

Related Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

Recent Posts

Minefields and maternity leave: why I fight a system that shuts out women and caregivers Candace Parker & Michael C. Bush on Purpose, Leadership and Meeting the MomentCourtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packagingRelated Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

Patrick Cramsie is a Partner at dbox, the international design and creative agency, and a writer on graphic design. He is the author of a comprehensive history of graphic design,

Patrick Cramsie is a Partner at dbox, the international design and creative agency, and a writer on graphic design. He is the author of a comprehensive history of graphic design,