In a

posting in February, I provided reasons Books Matter. In that necessarily short-handed list was a positing of Evidence as a crucial characteristic of the physical codex. More specifically, for historians, librarians, and bibliophiles, the evidence we focus on is marginalia — the annotations, ownership marks, commentary and corrections made in graphite and ink on printed pages. The principal value of these voluntarily additions is that they can provide unique context for a book’s history—from a student’s notes in a

sixteenth-century book on logic to a

toting up by H. L. Mencken of the liquor he consumed during a three-year period.

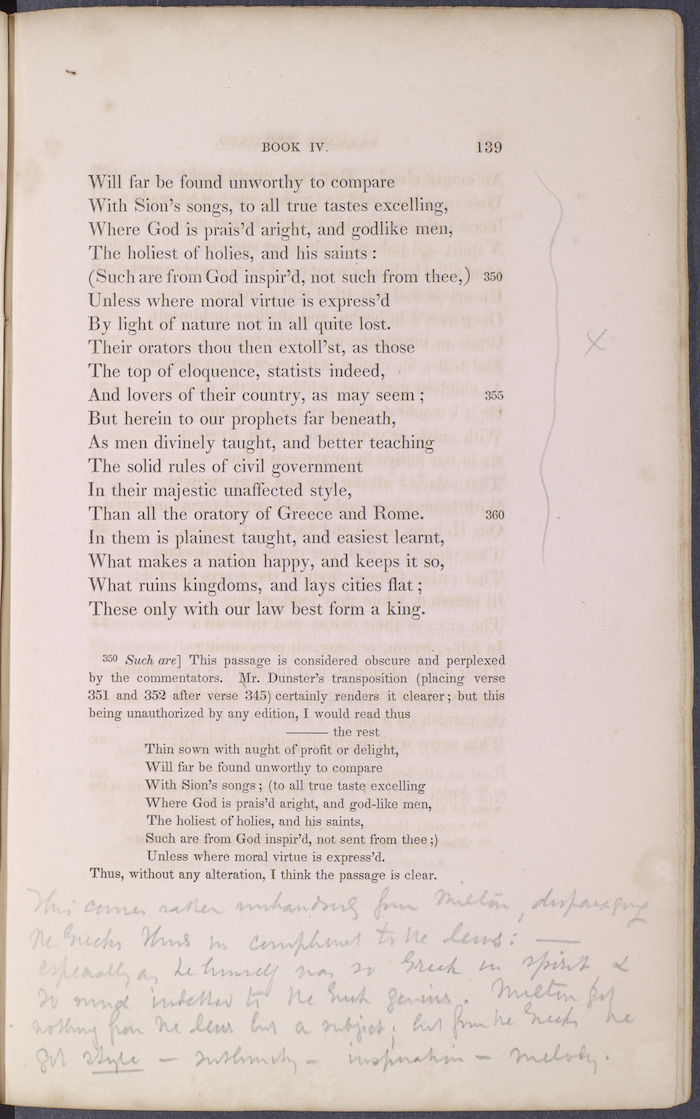

Evidence of use and reading remains the primary appeal of marginalia and annotations. But for poets and essayists, this added material can be seen as a dialogue, giving the (most often unidentified) reader a voice; an annotated book turns a lecture into a conversation. For Susan Howe, the dialogue between Herman Melville and his library led her to a long meditation on reading, influence and intellectual inheritance. She

observes, in “Melville’s Marginalia” that “margins speak of fringes of consciousness.” (This essay/poem can be found in Howe’s book

The Nonconformist’s Memorial, and the original catalog of Melville’s Marginalia has been put

online as well.)

Librarians may, as a group, be averse to borrowers of books writing in the appealing white spaces on their pages. Yet, a pair of projects run by scholars and libraries is intended to capture, record and give value to the presence of marginalia. The Provenance Online Project, as its name indicates, is aimed at recording the history of books through their ownership and transfer (between readers, collections and libraries) via the extra-bibliographic bits that are often added to printed volumes: bookplates. inscriptions, bindings, labels.

The focus of the project, originated by the special collections department of the University of Pennsylvania, is on early modern-era books, the kind that might normally receive specialized cataloging in rare book collections. The POP site will soon be adding more libraries as contributors, creating a core of digital images that will help librarians and book collectors better identify the marks and plates in their books. The most popular part of the site may well be “Mystery Monday” posts, where uncertain or undecipherable notations are presented for puzzle-solvers.

In comparison to the

Provenance Online Project, the Book Traces

website, linked in my February post, is a cooperative work launched in 2014 by Andrew Stauffer, Associate Professor of English at the University of Virginia, with the intention to capture annotations in books in circulating collections. Recording notes in books that are not housed in special collections is an elusive goal since such volumes would not normally be given the level of scrutiny that rare volumes get from catalogers. The Book Traces website encourages submissions of discoveries in books published from the nineteenth century up to 1923 (in order to allow clear out-of-copyright use online). So far, the website has added examples of ownership inscriptions, long commentaries on texts, drawings, and even musical passages written on fly leaves.

A possible bookend to Susan Howe’s working through Melville’s annotations would be Ander Monson’s

Letter to a Future Lover: Marginalia, Errata, Secrets, Inscriptions, and Other Ephemera Found in Libraries. Monson, in an act of meta-commentary, adds his responses to the responses he finds in books in various libraries he visits. While his brief essays can meander into encyclopedic asides on popular culture and technology, he does hit the target when he addresses anonymous markers of books. In “How to Read A Book”, he admonishes: “Dear undergraduate, let me tell you about rage: the defacing of the pages in the university library makes me want to get my box cutter and rain terrorism on your wee, thonged heart. I am all for marginalia, and Adler argues for this, but save it for a book you own or wrote or at least hope to fill with interesting argument …”

An argument for engaged annotating, to be sure: meaningful marginalia.