May 8, 2017

Why One of the First Waiting Rooms Designed for Children Involved Live Birds

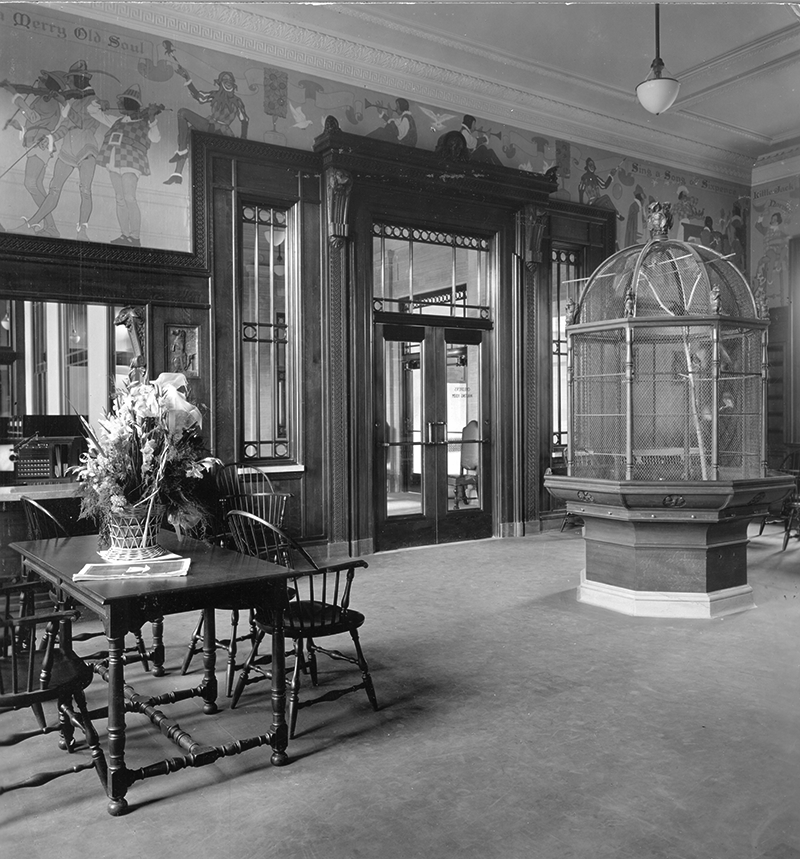

Rochester waiting room with aviary. Courtesy of the Eastman Dental Archives, Bibby Library, Eastman Institute for Oral Health

This past summer, on a drive through the Finger Lakes region of Upstate New York, I accidentally stumbled on the most beautiful waiting room in the world.

The room was the former gateway to the Rochester Dental Dispensary, which opened its doors in 1917 to cater to children from low-income families. This room was entirely unlike the spaces usually found upon entering early twentieth century clinics for low-income patients. Photographers Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine revealed those to be crowded, dim rooms, often not separated by walls from the operating theaters, and filled with wailing children who had to wait in lines so long that they sometimes died before seeing a doctor.

Waiting room from Jacob Riis’ The Children of the Poor.

In contrast to that purgatory, the waiting room at the Rochester children’s clinic was filled with light. It was spacious and high ceilinged. Moreover, in an era when children were only just starting to be thought of as something other than small adults, it was inarguably a space dedicated to young people. The room was filled with small rocking chairs for toddler-length legs to reach the floor. The oak trim and paneling on the walls were charmingly carved with animals. A springer spaniel’s muzzle peeked out from the door lintel. A sheep slept over the reception desk. A frieze of murals scrolled out Mother Goose stories—Old King Cole, Little Jack Horner lifting an exuberant thumb, and a painted jester perched on the door lintel and shaking a belled marotte. The colorful illustrations were like a musical story time, the music almost as tangible as the scent of the flowers that were brought in to freshen the air.

The flowers also served a practical function, because the most remarkable element of the Dispensary waiting room was an enormous aviary filled with live birds. Ringed by gargoyle-like squirrels guarding the cage, the birds fluttered behind the crosshatched walls—holes too small for even tiny fingers to poke through. No doubt, the aviary was the idea of William Bausch, the Dispensary advisor and the commissioner at the local zoo, which was most famous for its foreign and native birds collection. Short on design precedents for children-centered spaces, the clinic founders searched for places they knew children loved and ultimately created a combination of a nursery and a zoo. Rapt children would surround the songbirds as they called and twittered and their wings whirred in short flights. The goal was to make waiting to have your teeth cleaned at the Rochester Dispensary as entertaining as an hour at the zoo.

Eastman designed waiting room. Image courtesy of the Eastman Dental Archives, Bibby Library, Eastman Institute for Oral Health.

Why was the whimsical design of this waiting room so important? The clinic’s patron, philanthropist and Kodak founder George Eastman, endowed the institute with the aim to raise an entire generation of Rochester working class children with healthy teeth and gums. At a time when preventative healthcare such as teeth cleaning was virtually unknown as a medical practice, Eastman’s philanthropy targeted the lifetime health of the entire body. “Get hold of these children early,” Eastman told the Dispensary director. “If you keep their mouths in good condition, you will help their digestion and general health for the rest of their lives.”

There was more than altruism behind Eastman’s endowment of the clinic. His vision to ensure the good health of those who would otherwise be unable to access medical care had as much to do with the future of his company as it did with social good. At its peak, Kodak was the primary employer in Rochester; the generation Eastman treated at the Rochester Dental Clinic would grow up to be workers in his labs and factory. “Dollar for dollar,” Eastman said, “I got more from my investment in the Rochester Dental Dispensary than from anything else to which I contributed.”

In Jacob Riis’ book, The Other Half, which detailed his time photographing the working class, Riis bemoaned “the stubborn ignorance that dreads the hospital and the doctor above the discomfort.” The design of this waiting room—child-centered and cheerful, the birdcage as much an avatar for a zoo outing as the founders could supply—was the manifestation of design used to build partnerships with patients. For pervasive, generational success, it is not enough to remove barriers to access. The experience of the social program must be inviting and dignified in order to be successful and must be designed with the patient in mind to encourage use. The waiting room at the Rochester Dispensary was an early example of the importance of experience design in children’s public health programs, and elevated the clinic’s achievement beyond creating something merely accessible to something actually adopted by its intended audience—healthcare’s youngest users.

George Eastman planned for the Rochester Dental Dispensary to be a model used for replication in other cities, and ensured this by endowing children’s clinics in Brussels, Stockholm, London, Paris, and Rome. Not coincidentally, each location was home to a large branch of the Kodak company. And every waiting room had a bird cage.

Waiting rooms in Rome, London and Brussels, all designed by Eastman. Images courtesy of the Eastman Dental Archives, Bibby Library, Eastman Institute for Oral Health.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Emily Ludolph

Related Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

Recent Posts

Minefields and maternity leave: why I fight a system that shuts out women and caregivers Candace Parker & Michael C. Bush on Purpose, Leadership and Meeting the MomentCourtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packagingRelated Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays