January 4, 2017

Why the Gettysburg Address Is a Call to Bring Design into Government

“Designers often think of themselves as problem solvers: so let’s start solving some problems.”

—Jessica Helfand and Michael Bierut, “Let’s Get to Work”

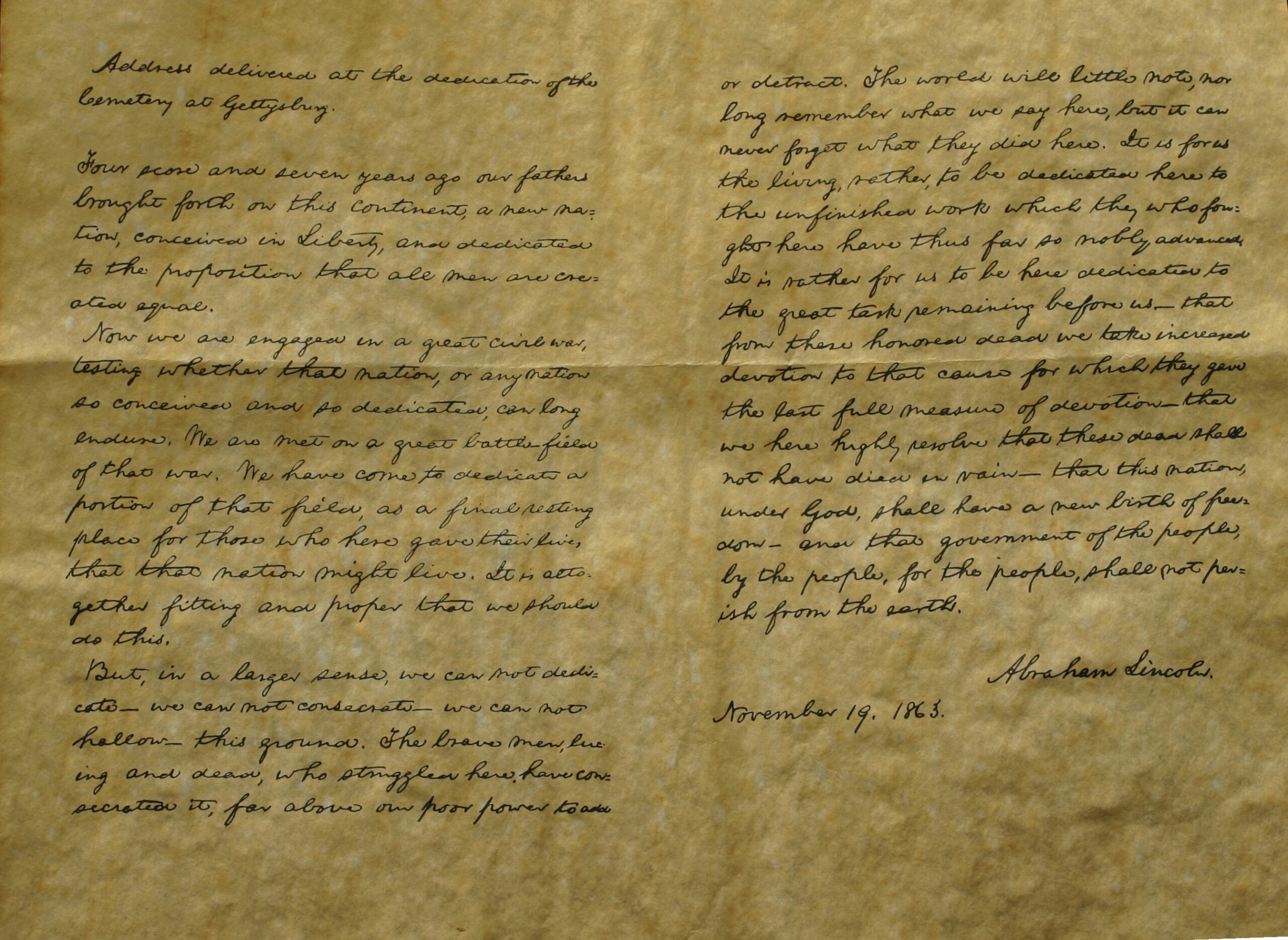

Consider the famous rhythms of the Gettysburg Address, in which Abraham Lincoln speaks of a government “of the people, by the people, for the people.” It’s still inspiring rhetoric, 153 years after it was delivered, and yet, when we think about our own American experience, few find it quite as people-focused as Lincoln promised. But what if we, citizens and politicians alike, took the Address seriously? Suppose that “people” was the force, above all other forces, that pressed on government and kept it democratic, vital, real. What might that look and feel like?

Our recent election vigorously demonstrated that America hungers for a truer dialogue, and a government in which people are a truly significant part of the process. As the New York Times suggests, the current means of understanding the citizenry—relying chiefly on data—may not be the best way. The question is: How might we improve the level of dialogue between the people and their representatives? How could we work together to improve civic projects such as collecting garbage or communicating Medicare benefits to the elderly? The answer is: with design. Lincoln’s language naturally maps onto the designer’s ethos and politicians, at every level, would do well to incorporate our process into theirs.

Of the People

Designers begin by engaging in what’s called ethnographic research. We get out into the world and meet people in the places the live: on the job, in their houses, in hospitals, wherever products and services are used. We’re all about fieldwork. Well-versed in the arts of listening to and observing people in their natural contexts, we invest time in building relationships. That is, we get out into the world and get to know people; we ask lots of questions and hang around until we get it. Until we get what’s wrong.

Governments should learn the fine points of fieldwork. Equip a politician with empathic interviewing skills, and you’ve created a whole new kind of politician. Creating relationships that produce valuable qualitative data—the sort you won’t get from a cold survey—will give them what’s needed to design policy successfully.

By the People

Once designers synthesize and analyze what we’ve learned, iterative prototyping begins. That is, we create an early, and not necessarily polished, version of the thing we’ve dreamed up to address the insights that surfaced during the ethnographic era. We then return to our people and ask them what they think of our makeshift service or design. The idea is to get their informed feedback, so that they evolve the prototype and make it better, more useful, more appealing to them. In doing so, they become co-designers.

Thinking of citizens as politicians’ design partners might be a healthy way to view governance. Such an approach would empower ordinary people and increase faith in government. In addition, testing early stage projects with informed engaged citizens, on a small scale, might save money and time and cut down considerably on everybody’s frustration. Think of how many Affordable Care Act headaches the Obama Administration might have avoided if they spent more time iterating the program with small groups of people, testing early versions and continuously tweaking, rather than rolling it out as one big, not-quite-finished, considerably imperfect, project.

For the People

What happens when we bring together all this ethnography and prototyping and iteration? Taken in concert, they aim to ensure that the product or service being developed works for the people who will be using it. Design must always return to the needs and wants of its users. Well-designed policy design will, similarly, always return to the needs and wants of its citizens.

When politicians view the world with a designer’s eye, their constituents truly become people. Design thus serves as a corrective to the standard instrumental view of voters and acts, perhaps, as system of checks and balances on politicians’ thoughts and actions.

Getting to Work

So how might we—how might you—start actually helping design of policy? First, start local. Get to know the relevant officials in your city. (Cities, we should note, will take an increasingly important role as Obama exits office.) Engage with these leaders on Twitter. Show up for civic meetings, and offer your three cents. Read the metro section of your local paper, note which public projects appeal to you, and then write to the leaders involved and demonstrate how design might help cause. While you’re learning about the local scene, you should also learn about larger trends in civic design: Read pubs such as CityLab and, if you’re so inclined, attend conferences like CityAge. The better you understand the language of civic work, the more effective you’ll be as an ambassador of design.

Now imagine designers in every city following your good example! The notion of consciously incorporating citizens at all steps of policy design, of thinking about government work as an iterative partnership with the people, seems just like what Lincoln prescribed for the nation after the self-inflicted wounds of the Civil War. Could design help restore a sense of unity and harmony to our fractured political life? It might—but designers will clearly have to make the first move. As Lincoln might say: “It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.”

Observed

View all

Observed

By Ken Gordon

Related Posts

The Observatory

Delaney Rebernik|Analysis

A story of bad experiential design

The Observatory

Ellen McGirt|Essays

Lessons in wandering

Architecture

Sameedha Mahajan|Design and Climate Change

The airport as borderland: gateways for some, barriers for others

The Observatory

Alexis Haut|Analysis

“Pay us what you owe us”

Related Posts

The Observatory

Delaney Rebernik|Analysis

A story of bad experiential design

The Observatory

Ellen McGirt|Essays

Lessons in wandering

Architecture

Sameedha Mahajan|Design and Climate Change

The airport as borderland: gateways for some, barriers for others

The Observatory

Alexis Haut|Analysis