February 8, 2012

On My Shelf: A Classic by Berger and Mohr

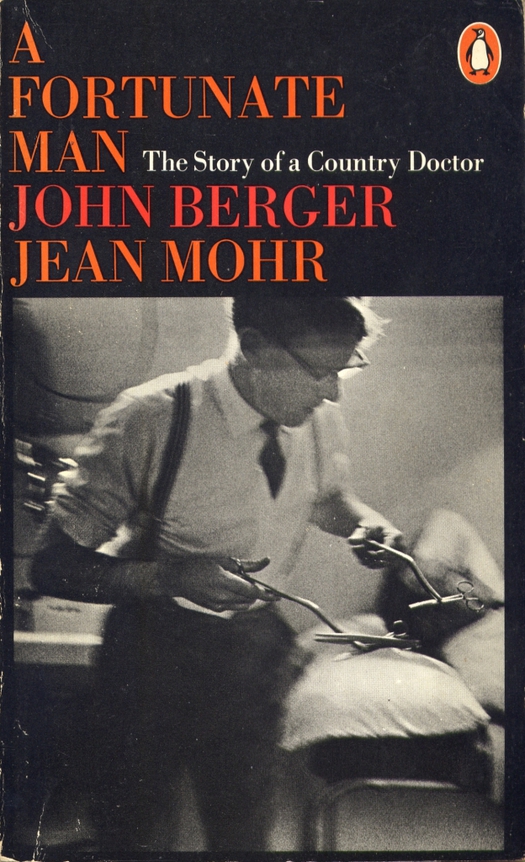

A Fortunate Man, Penguin Books, 1969. Photograph: Jean Mohr

For a book that can justly be called a masterpiece, John Berger and Jean Mohr’s A Fortunate Man: The Story of a Country Doctor, first published by Allen Lane in 1967, is not nearly as well known as it should be. A brilliant fusion of text and photographs, it had been out of print in the UK for many years when the Royal College of General Practitioners reprinted it in 2003 in a limited edition. That edition aimed at the medical profession was never widely distributed and is no longer available. (A Fortunate Man has fared better in the US, where Vintage’s 1997 edition is still in print.) But not even its unavailability can explain how Martin Parr and Gerry Badger came to leave it out of their monumental, two-volume The Photobook: A History — perhaps its hybrid nature disqualified it.

Among doctors who know A Fortunate Man, the book enjoys a lasting reputation. In 2005, the British Journal of General Practice dubbed it “still the most important book about general practice ever written.” Dr Gene Feder, who wrote the accompanying article, recalls reading it as a medical student and thinking, “this is why I want to be a doctor.” At a celebratory evening for the book held in London in 2005, Dr Iona Heath, one of the panel of speakers, declared, “If I could choose only one book on the planet, it would be this book.”

Readers Union & Allen Lane, book club edition, 1968. Jacket design: Terry James

Vintage Books, 1997. Art direction: Susan Mitchell. Design: Marc J. Cohen: Photographs: Jean Mohr

Royal College of General Practitioners, 2003. Design: Layne Milner & Patrick O’Brien. Photographs: Jean Mohr

The interest of A Fortunate Man goes much wider than these professional testimonials might suggest. The book is a study of a doctor’s life in a small rural community in 1960s Britain that addresses fundamental questions about the doctor-patient relationship and what it means to assume and bear such responsibilities as a healer. Berger met John Sassall when he went to see him with stomach pain, and they later became friends. When the writer, who had subsequently moved to Geneva, suggested that he would like to write about Sassall, the doctor gave his assent, allowing Berger and Mohr, a Swiss photographer, to accompany him on his rounds and observe his examinations and treatments for six weeks. In both the closely observed, meditative writing and the sensitive black-and-white pictures of Sassall and his patients, the book achieves a remarkable and often deeply affecting empathy and intimacy without seeming intrusive. Berger describes Sassall, the untiring witness or his patients’ lives, as being “like a foreigner who has become, by request, the clerk of their records.”

In 1965, in an article in Typographica no. 11, Berger argued the need for new relations between words and images: “No editor yet thinks of a photographic library as a possible vocabulary; nobody dares to place images as precisely in relation to a text as a quotation would be placed; few writers yet think of using pictures to make their argument.” His most famous book, Ways of Seeing (1972), designed by Richard Hollis, applies exactly this principle.

A Fortunate Man, the first in a trilogy of innovative collaborations with Mohr — see also A Seventh Man (1975) and Another Way of Telling (1982) — was Berger’s first book-length attempt to mix words and images together in a way that invited readers to treat them on their own terms as contiguous but distinct kinds of information. Berger and Mohr had certainly seen Walker Evans and James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941) about sharecropper families in the depression, though the photographic section and Agee’s documentary text are not permitted to intermingle in that book. And it’s possible that they were also aware of W. Eugene Smith’s ground-breaking “Country Doctor” photo-story in Life, October 11, 1948. “Both Jean and I have a considerable admiration for Eugene Smith,” Berger writes in their book At the Edge of the World (1999).

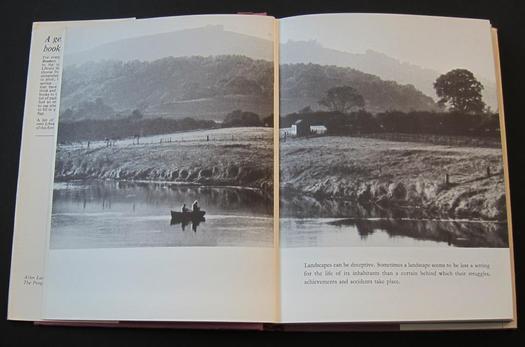

A Fortunate, Man, Readers Union edition, pages 10 & 11. Design: Gerald Cinamon. All photographs: Jean Mohr

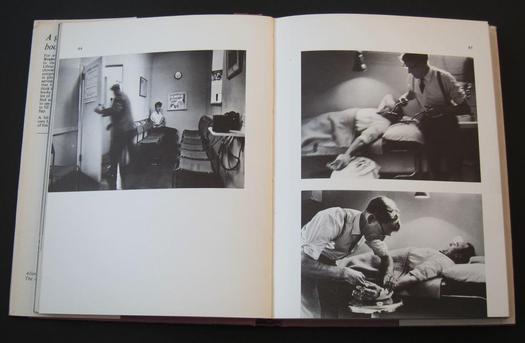

Readers Union edition, pages 44 & 45

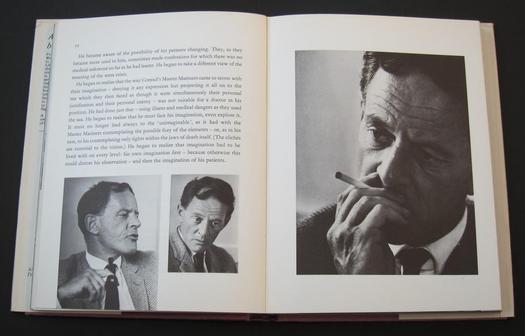

The transitions from text to image and back again in A Fortunate Man are perfectly judged, each medium given the space to speak in its own manner. In the spread shown below, Berger has just recounted, with no sensationalism, a story about how Sassall discovered during an examination that an elderly man’s wife was also a man. Then he moves on to discuss how the doctor came to understand that he must confront his own imagination. “He began to realize that imagination had to be lived with on every level: his own imagination first — because otherwise this could distort his observation — and then the imagination of his patients.” In the four character studies by Mohr that follow, Sassall is forthright, concerned (even anxious), and introspective. Over the page, next to the fourth portrait, in which Sassall’s eyes seem to bulge with watery sadness and surprise, Berger describes his attempt at Freudian self-analysis and his temporary impotence.

Readers Union edition, pages 52 & 53

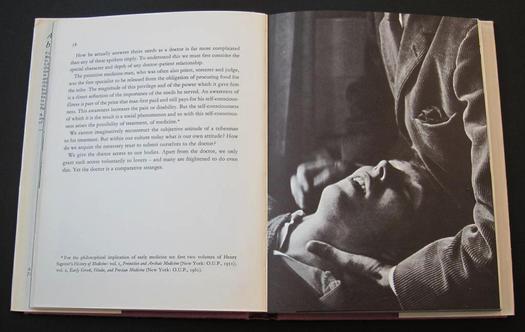

A few pages later, Berger considers the access we give doctors — comparative strangers — to our bodies. In place of description, we see Sassall touching a recumbent patient’s outstretched neck, the first in a sequence of similar images.

Readers Union edition, pages 58 & 59

In the passage that faces the picture below of Sassall at work with a nurse, Berger describes the look of relief he sees on the doctor’s face whenever he is engaged in a task that permits certainty because it can be done well or badly. The text resumes three pages later after two more pictures of the scene.

Readers Union edition, pages 78 & 79

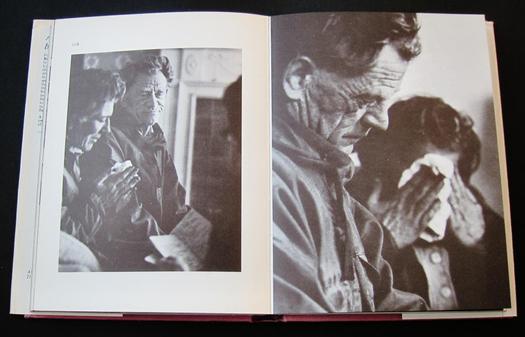

A sequence of five images of a grieving family follows a passage in which Berger talks about the time-scale of the anguish that a doctor must witness.

Readers Union edition, pages 108 & 109

Sassall struggles to reconcile his concern for his patients with his understanding of the restricted lives their circumstances will bring them. This is the final spread in a sequence of six pictures showing the social lives of young people in the village.

Readers Union edition, pages 130 & 131

Gerald Cinamon, who had previously designed Berger’s Success and Failure of Picasso (1965), also for Penguin, designed both the hardback and paperback versions of A Fortunate Man. In an essay about Sassall and A Fortunate Man published in The Lancet medical journal in 2001, J.S. Huntley notes that, “The authors, as a condition of publication, retained the right to the minutiae of the book’s layout: the position of the text on the page, the position of the pictures within the book, the combination of text, page turn, and picture.” The source of this information must have been Berger, interviewed by Huntley in 1999. For his part, Cinamon doesn’t recall any contact with Mohr about the book. “I can’t remember if the photos were presented to me ‘in order.’ They may have been (by the editor). But John Berger was happy with the first book I designed for him so may have just let me get on with it. I did go to Geneva to show him my paste-up for the Picasso but I certainly don’t remember repeating that for this book.”

The publication of the Penguin paperback in 1969 necessitated a redesign of the entire book because the standard page size is substantially narrower relative to the height. (All the spreads shown here are from the hardback.) Cinamon moved pictures to different pages and sometimes changed the order of pictures within a section. He was also obliged to crop images to fit the narrower width; there are fewer full-bleed images and less scope for changes in scale between pictures. The paperback layout still works — this is the version reprinted at a larger size in the Vintage paperback — but it’s not as satisfying as the hardback layout, and the printing of the halftones, which have darker blacks, was also better in the original (this was the version reprinted by the Royal College of GPs, though its cover let it down).

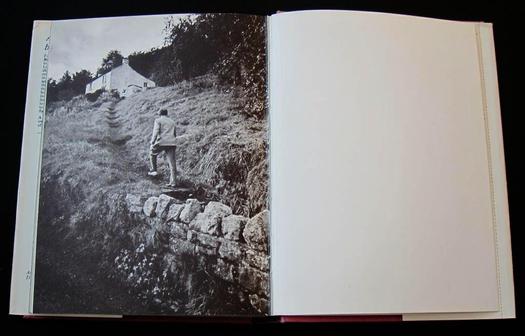

Readers Union edition, page 158

Perhaps the most striking change Cinamon made in the paperback was to the final image of Sassall climbing the path to his house. “I hesitate to admit that, to make more visual sense of the ending of the book, I reversed the photograph so that the doctor was trudging off the right-hand page — nothing less than a criminal act! I hope I had Berger’s approval,” he writes in an unpublished private note he made about his design. On the following spread, Cinamon also repeats the central detail of Sassall climbing: a kind of cinematic “iris-in.” For me, these devices don’t feel necessary, though most of the book’s readers will know it in this form. The original Sisyphean image, in which Sassall seems to double back and return with a determined stride to the pages of his own story, is perfectly appropriate to the intense, troubled nature of the man and the book’s inward-turning reflectiveness.

With hindsight, the original picture is fitting in another way. Fifteen years after A Fortunate Man appeared, Sassall shot himself. As Berger writes in the book, he had always been prone to deep depressions lasting months, precipitated by “the suffering of his patients and his own sense of inadequacy.” In an afterword added to the 2003 edition, Berger suggests that Sassall’s suicide has made the story of his life more mysterious but not darker. The knowledge certainly changes one’s reading of a book that was ahead of its time — W.G. Sebald is an obvious later reference point — in its interconnecting narratives of text and photography. Given Berger’s international stature as a writer, and Mohr’s equally sustained achievements as a photographer, A Fortunate Man is surely an urgent candidate for republication in a new fully restored and annotated edition of the original fluid design.

See also:

W.G. Sebald: Writing with Pictures

On the Threshold of Sebald’s Room

Observed

View all

Observed

By Rick Poynor

Related Posts

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

The Observatory

Ellen McGirt|Books

Parable of the Redesigner

Arts + Culture

Jessica Helfand|Essays

Véronique Vienne : A Remembrance

Recent Posts

Why scaling back on equity is more than risky — it’s economically irresponsible Beauty queenpin: ‘Deli Boys’ makeup head Nesrin Ismail on cosmetics as masks and mirrors Compassionate Design, Career Advice and Leaving 18F with Designer Ethan Marcotte Mine the $3.1T gap: Workplace gender equity is a growth imperative in an era of uncertaintyRelated Posts

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

The Observatory

Ellen McGirt|Books

Parable of the Redesigner

Arts + Culture

Jessica Helfand|Essays

Rick Poynor is a writer, critic, lecturer and curator, specialising in design, media, photography and visual culture. He founded Eye, co-founded Design Observer, and contributes columns to Eye and Print. His latest book is Uncanny: Surrealism and Graphic Design.

Rick Poynor is a writer, critic, lecturer and curator, specialising in design, media, photography and visual culture. He founded Eye, co-founded Design Observer, and contributes columns to Eye and Print. His latest book is Uncanny: Surrealism and Graphic Design.