As the new decade gets underway, sustainability continues to occupy more of our collective brainpans, hogging more spotlight on the world stage and settling into its role as the defining issue of our times, poised to engulf our culture and our society. As more designers incorporate its principles into their personal and professional lives, AIGA has incubated a new framework to focus the sustainable efforts of the design community at large — The Living Principles for Design."

Over the past few years, design support industries (i.e., paper and printing) and adjacent disciplines (i.e., architecture and industrial design) have been busy as well. What has emerged in many instances is a central pivot point, a common frame of reference around which these industries and professions can revolve. In the paper industry, Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification has become the principle means by which timber products are evaluated. Likewise — and perhaps most significantly — the world of architecture has its ubiquitous LEED standards. The Okala guidelines provide focus for the industrial design community, which, like architecture, is very much in the business of making stuff: fixed artifacts defined primarily by their physical form and function. Other initiatives such as The Designers Accord reach across disciplines, as do AIGA’s Living Principles for Design.

Download a PDF of the Living Principles for Design framework here.

The Ghost in the Shell

Sustainability plays a different role relevant to communication design. There is indeed some physicality to the things that designers create — paper (and printing), packaging, exhibitions, installations and the electronic devices that carry our messages all harbor a variety of ecological consequences. And while it is true that as specifiers, designers exert some degree of control over (and thus responsibility for) how these things exist in the world, the molecules of our profession are simply not as interesting as those found in other disciplines, nor are they as central to the way design inhabits our minds. Designers create messages and experiences that leave indelible impressions as they flow through people’s hearts and hands. In the grand scheme of things, these impressions are much more significant than whatever percentage of post-consumer waste might exist in the ephemeral substrate upon which they are delivered.

The design community — those of us who would call ourselves graphic, interactive or communication designers — has not had the benefit of a common lens through which we can relate to sustainability, particularly sustainability defined in its broadest measure, beyond issues of recycling and environmental concerns. Nor are there any commonly-accepted means to account for the real power of design: the ability to create meaningful messages that change minds, shift behavior, connect people to ideas, rewrite cultural norms or envision new ways of living our lives. This transformative power of design shapes our world and represents tremendous opportunity related to sustainability and an understanding of its broader applications. Using this power in a meaningful way requires integrating existing tools and demonstrating how they can be applied in business and social contexts. As designers continue to move into more strategic relationships with their clients and/or forge their way into previously unchartered territory, having an inclusive and malleable framework for sustainability is crucial.

The Knowledge Hairball

Ongoing AIGA outreach indicates that most designers consider sustainability to be very important to their business. But as designers attempt to fold sustainable principles into their everyday design practice, they are finding that it can be daunting. Sustainability is complex and entails a steep learning curve. Who has time to unravel the knowledge hairball represented by the myriad books, articles, Web sites, frameworks, reporting schemes, calculators, standards and manifestos?

The first step in converting all of this information into a body of knowledge useful to the design community was the creation of a “Genealogy” document. Rather than start from scratch, it was decided to build upon other commonly-accepted and recognized frameworks, acknowledging and expanding them. AIGA executive director Ric Grefé notes, “The framework that has emerged — The Living Principles for Design — is not intended to be different or more perceptive than others, but rather to make the work of others more accessible to those who have neither the exposure to what has come before nor the time to integrate those efforts into a single credo.”

The Secret Sauce

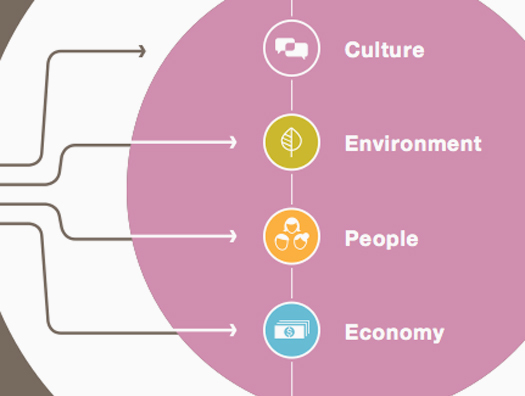

Sometimes referred to as “people, profit, planet” or the “triple bottom line,” many existing frameworks account for three distinct components: environmental protection, social equity and economic health. What makes the Living Principles unique is the inclusion of a fourth stream that recognizes the critical need for cultural assimilation of this knowledge. As designers, we make our living selling intangibles, it follows that we should have a framework that accounts for this fact. Our work has properties that are difficult to quantify, but are the key to design’s power. If we are to create meaningful change — to instill everyone with the ecological intelligence necessary to build a better world — then we need to help make good messages.

Each of these four streams presents opportunities and challenges for designers, but they must work together in concert. The Living Principles also asks designers to consider the relative impact of their efforts, examine the various ways we are connected to sustainability and endeavor to participate in areas of wider scope. In addition to helping apply sustainability in more integrated fashion, the Living Principles will also serve as a common touchstone: the portal through which everyone passes on their way to learn about sustainability, and the communal resource to which everyone returns to share what they have found. By remaining creatively agnostic, the Living Principles will become a body of knowledge to which numerous creative disciplines and their business partners can develop and refer.

There is no end to this journey, it has no fixed outcome and there are still more questions than answers. But not having those answers shouldn’t prevent us from having the conversation. Please consult the Web site and join the Facebook group to be part of it all.

Visit the Living Principles website. This article is reprinted here with kind permission of Communication Arts.

Comments [4]

This also leads into another problem: the capacity of triple bottom line thinking to deliver a more sustainable future is nil unless each of the categories deployed are subject to radical critique. These are not just tick-a-box criteria. They are concepts constructed within the context of the unsustainable and they bear its mark. If we are dealing with inherently destructive conceptions of environment, people, and economy, it is not enough just to 'take them into account'. They must be re-constructed (or abandoned) in the interests of the sustainable and against (yes, there must be a naming of an antagonism) the unsustainable.

In short, given the constraints of existing practice, I think designers need a way of learning how to sit with and interrogate a problem through wider and varied dimensions that are not always pragmatically orientated. Icons, circles, and arrows can be useful, and they certainly look neat, but shaking the link between design and the unsustainable will require more substantial thinking.

04.13.11

09:42

12.30.11

05:02

Micheal,

08.10.12

07:28

08.21.12

08:48