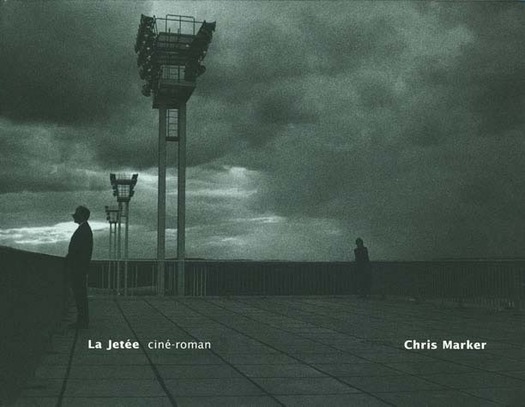

For years, I've owned a copy of La Jetée, a book about the film by Chris Marker, the experimental filmmaker. Designed by Bruce Mau and published by MIT Press/Zone Books in 1993, this is one of those design books that has ascended into the realm of rare bookdom (like Learning from Las Vegas); not a single copy is offered online today, and a seasoned dealer would catalogue a fine copy for over $500, even perhaps over $1000. While Zone was the project where Mau first established himself as an intellectual designer, these were generally text-laden monographs for an esoteric scholarly audience. La Jetee, the book, is different: a photo-novel ("ciné-roman") with no text except for captioned narration. I have always thought of it as the mother of the full-bled-photography thing that Mau is known for, and that has since become a frequent conceit in contemporary design publishing.

Then I saw the film. I love the book, but it becomes only a book in the face of its original media. I remember more of this movie than the previous hundred movies I've seen. La Jetée is constructed in still images; it is a movie of photographs. The implications of this, and the statement — "I remember more..." — are enormous.

La Jetée is a 28-minute experimental film made in 1962. Though I studied film in college, I managed to miss it. It shows up as a trendy icon of cultural studies, like Jean Baudrillard or Guy Debord, in student bibliographies (frequently in those I see from Yale); in new histories of the cinema; and even through Netflix, where I finally encountered it. La Jetée is its own special occasion. Scenes are inspired by Vertigo (Hitchcock, 1958). And it inspired the story of 12 Monkeys (Terry Gilliam, 1995). I have seen both films a couple of times and remember numerous segments. Yet, I have the most precise and vivid memory of almost every image in La Jetée.

La Jetée is a story of memory. As described by film critic Jaime Christley: "it's present-day Paris, where a young boy sees a beautiful woman at an airport, and then sees a man die of a gunshot wound from an unknown assailant. Years later, following an apocalyptic disaster that has driven a decimated mankind into underground bunkers, the boy — now grown — is afflicted by his memory of the beautiful woman so strongly that government scientists wish to use it as a means for time travel, with the hope of finding a key to restoring the world to its former condition. Naturally, he meets the woman and falls in love with her."

This description of the narrative downplays the impact of the imagery. His time travel occurs through the most makeshift of experiments; he becomes a monster resembling nothing less than the madness portrayed in the photographs of Joel Peter Witkin. As a man encountering his lover, one can only think of the films of Claude LeLouche, which would come years in the future. In our time, one is reminded especially of the Matrix. In 28 short minutes, and a few hundred still images, La Jetée competes in my mind with the most dramatic three-part, six-hour science fiction epic that Hollywood can serve up.

The photographer as editor as designer as movie-maker is all contained within the genius of La Jetée. As it stirs our emotions with memories, it also makes possible the construction of a never-to-be forgotten narrative sequence. It's so simple. It's the ultimate visual essay, the epic novel told in the most minimal and constrained number of images.

Comments [10]

Print some more, it is really easy. Or is scarcity "cool" like water.

As for the movie "It's the ultimate visual essay, the epic novel told in the most minimal and constained number of images."

That is not true. Zero images is the most constrained, but that involves no time. Nor does a single image. Two images, (or zero to one), is the true minimum for a time based essay.

And, I find most anything by Tufte's to be more ultimate. My downstairs neighbor might find Groening more ultimate than either.

La Jetée plays with time thoroughly, both in style and plot. However you must keep in mind that while the images are "still" the audio is not.

Image can exist within a frozen moment, but audio can not. Sound and music are one with time, but image and sight can break free.

Or so our senses like us to think. But really an image is a segment of time, captured at the shutter speed or frame rate of the camera.

It is just audio does not have the resolution of image to tell a story in a 1/60th of second.

To focus on the image of La Jetée would be to miss the story. Through narration and subtitles the story unfolds. Without either it would be beautiful, but difficult, perhaps impossible, to understand.

After you see La Jetée, see Sans soleil.

Contradiction, like the notion of randomness, is necessary to understand something more complex than oneself.

02.06.05

04:29

Simliarly, Twelve Monkeys is amazingly effective for a fairly overblown Hollywoodization of a simple, lovely original, more testimony to the power of the basic idea. Designers may be interested in another precedent for Gilliam's film: the fantastical architectural renderings of Lebbeus Woods. The movie's production designers more or less "built" some of Woods's renderings without crediting him, most notably the room with the elevated chair that Bruce Willis is interrogated in. Woods sued and actually got a temporary injuction issued to halt distribution of the film about a month into its release. The film's designers used the unlikely (and unsuccessful) defense that they had seen Woods's drawings somewhere and, in effect, made the memory real. Ironic.

02.06.05

09:25

02.06.05

10:57

I saw La Jetée first, and after seeing Night and Fog -- with its real images of Auschwitz -- La Jetée seemed less powerful to me. Of course Night and Fog uses images of a powerfully specific place and event to assemble memory, and the reality of its historical subject makes the film itself something of an artifact (or perhaps like the buildings and events depicted, a ruin) of memory. Formally La Jetée describes similar mechanisms of memory, and in doing so it might be seen as a peculiar simulation of the earlier film.

02.06.05

05:10

Bill, Perhaps it's because of my fortune to be raised in western New York — smack between Hollis Frampton's Center for Media Study in Buffalo and the Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester — that when I read your post I realized the irony of how you (and many of our colleagues in the visual arts) may be overlooking Language's superiority over Image in La Jetée:.

A quote from Lucy Fischer's essay "Sound Waves":

Avant-garde artist Stan Brakhage, for example, made a conscious choice at some point in his career to treat cinema as primarily a pictorial medium. As he wrote in a letter to Ronna Page in 1966: I now see/feel no more absolute necessity for a sound track than a painter feels the need to exhibit a painting with a recorded musical background.

Opposing this point of view over the course of cinema's history has been a group of artists who regard sound as a desirable, even requisite, element of the film. In the transitional years of 1926 and 1927 when acoustic technology took over the industry, Rouben Mamoulian was immediately impressed by "the magic of sound recording" that "enabled [him] to achieve effects that would be impossible and unnatural on the stage or in real life, yet meaningful and eloquent on the screen."' Likewise, Jacques Tati has called the sound track "of capital importance,"' and Orson Welles has claimed that language is, for him, the essence of cinema. "I know that in theory the word is secondary," he has remarked, "but the secret of my work is that everything is based on the word. I do not make silent films." More recently, avant-garde artist Paul Sharits has deemed the relation of sound to visuals "the most engaging problem of 'cinema."'

Because La Jetée is mainly composed of still images — with one moving-image sequence of the woman's fluttering eyelids — the narrative, the 'caption', tells the story. It's really not a visual work; but it did make rich material for budding structuralist filmmakers and post-structuralist theorists.

You may be interested that much of Frampton's critical writings center on the problem (?) of language in film and photography. And I can also highly recommend his films nostalgia and Poetic Justice (not the Janet Jackson version). Both play with the frission between language and image in an accessible manner akin to La Jetée. In fact, Poetic Justice was reproduced in book form years before La Jetée.

To misquote Pauline Kael: We murmur 'Language' and they are sunk.

02.07.05

04:37

It still gets me, even after having watched it somewhere around 25 times. But, unless my copy is old and worn (and that's a great possibility), one of the frames is a motion picture--take a look at the part when the woman's face is on screen for some time, she clearly blinks. If it is real, and not the product of an ancient VHS relic, it's certainly beautiful that Marker chose that simple action to lend movement to.

02.07.05

11:03

Marker's CD-ROM, 'Immemory,' is also fascinating. The blurb on the package compares Marker to Proust, which may be a stretch, but as an artist who uses his own memories to make you think about the whole state of memory, he's in a fairly exalted class.

02.07.05

11:20

02.07.05

12:29

It's interesting how the way people come to La Jetee influences their perception of it. I first saw it as evidence that while cinema was image+sound, it didn't have to be moving image. OR moving camera. The mise en scene of photographs, so to speak, was plenty. Of course, this perception was, in part, because I saw it only after soaking in more traditionally made films that treated action and camera movement as the stars of the show.

Also: now I gots to find me that book.

02.08.05

09:41

02.08.05

10:13