A melting pot. A quilt. These are convtentional metaphors for the modern city, but if you ask me, a better choice is the sandwich. What's more urban than a sandwich, ideally a pastrami on rye, from a good deli? Throw in a Dr. Brown's and a pickle and you've really got something: a combination of flavors that together make something complex but with a little bite to it, something that may not be entirely good for you but sure tastes great and how could you live without it? That's a city defined right there.

Maybe I'm not the most objective source on this score, however. I'm from a deli family. My great-grandfather was the co-founding proprietor of one of the city's best, Fine & Schapiro. He was the Schapiro, an immigrant from the Russian Pale who landed in New York in 1906 and worked a pushcart on the Lower East Side. That stand became a grocery up in Washington Heights, and then the delicatessen, which still stands on 72nd Street between Broadway and Amsterdam. That restaurant opened in 1927, the year the Yanks won 110 games and the World Series, and the Babe busted his own record with 60 homers. He lived a block a way, in the Ansonia, and it's hard to imagine, given his outsize appetite, that he was not an occassional customer. Was some of his legendary power drawn from our old family recipes and the store's generous portions? I'm going to presume yes.

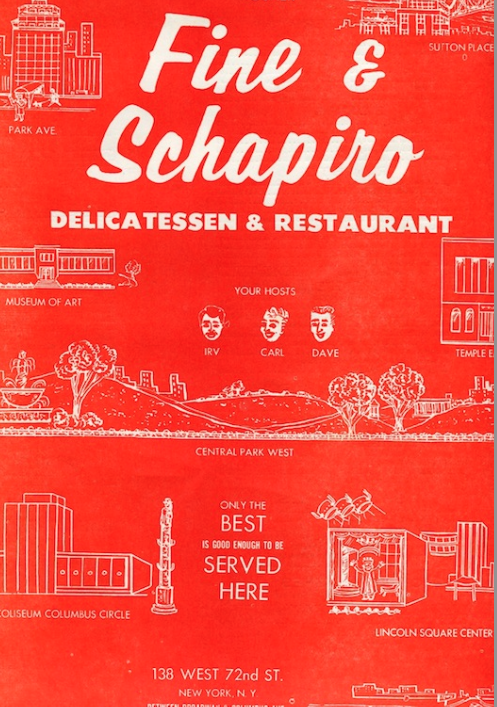

My mother worked at the store, and my grandmother before her, but I never had the chance. When I was young, it was run by my uncle Davey, a benevolent presence behind the counter in the deli man's trademark paper cap. You can see him smiling at right above, in the charming line drawing that appears on the cover of a 1964 menu, from the wonderful collection of menus at the NYPL. (A big thanks to Rebecca Federman for passing it along.) The bright orange sets a sprightly tone, as does the marker-style script, and the naive illustration—a telling selection of New York landmarks, rendered without much fidelity by someone who apparently had little familariity with the city. There's the Metropolitan, Temple Emanu-El, Lincoln "Square" Center (then brand new), Park Avenue, Sutton Place, Central Park West.

A hot pastrami on rye cost all of $1.15 back then. Today it's $12.95. Chicken mushroom chow mein went for $2.95—Chinese takeout, always an Upper West Side favorite, was an option from the start. And of course there were those defining Jewish delicacies with the unappetizing names: stuffed derma, kreplach, gefilte fish, and—to my childhood horror—ptcha, a dish of calves foot suspended in a mucous-like, garlic-infused jelly. Ptcha—you can't even say it without spitting. This was a defining shtetl dish, but it occurs to me now that, only slightly modified, it would be right at home on a tasting menu at some hotspot of modernist cuisine where every course is a dare.

The family sold the place in the early 1990s, and in truth it hasn't been the same since. In the intervening years, the new owners opened a satelite in the basement retail concourse of the World Trade Center, and it was burried there on 9/11. And so the family name, by some macabre coincidence, is associated with that catastrophic day.

In Dallas, my new home, a brisket becomes not pastrami but barbecue. The local technique is to smoke the meat for a long period, and if it's done properly no sauce is required. Unlike pastrami, which thoroughly transforms a cut of brisket into something entirely new, barbecued brisket still retains an essential briskety flavor. Which is to say, it is linked in my mind to that other great (or terrible, depending on your perspective) tradition of Jewish life: the holiday brisket, cooked into a brownish gray submission by Jewish mothers everywhere.

Whatever the preparation, these dishes are the stuff of community, and to get back around to the original point, fine metaphors for urban life. Something to mull over lunch.

—@marklamster