The nineteenth century was a fertile time in Western societies, a time of exploration, colonial expansion, science and art. Newspapers were often reporting on adventurous exploits by adventurers of the day. Dinosaur bones and skeletons were all the rage in museums. With new inventions and industrial expansion driving commerce and imports arriving from faraway lands, it was an exciting period in which to live. Birds were captured and home aviaries were in vogue at the same time that the passenger pigeon was hunted into extinction.

Angelucci states that “the same colonial enterprise that drove the Victorians to expand their rule to a quarter of the world's land and a fifth of its population, spurred a sense of callous entitlement over its creatures, hunted for sport and captured for the pleasure of entertainment.” The poor passenger pigeon, once numbering in the billions, was hunted to extinction. It was this indifference to animals as well as fascination to them that led to grand parlors in Victorian high society homes, replete with cabinets of curiosity, taxidermied animals and birds, photo albums, minerals, fossils, and the like. The more complete your collection, the more refined you were considered by your neighbors and peers. Simultaneously, this interest in the natural world was as keen as their interest in the spirit world. Seances were popular, and a belief that the dead were “close by” made the fakery of spirit photographs an easy sell to unsuspecting patrons of photographic studios. Mourning the dead in those days was elevated to “grand public spectacles”, so it came to bear that “mourning photographs” (even post-mortem images) were an important part of society as well.

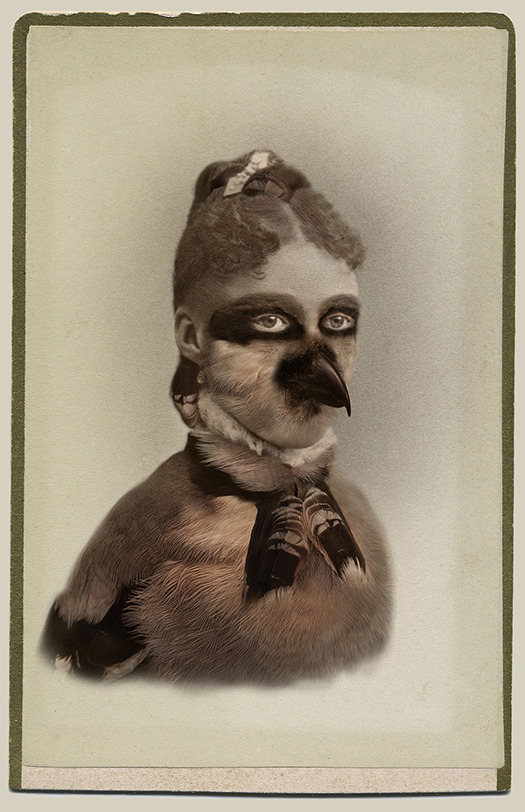

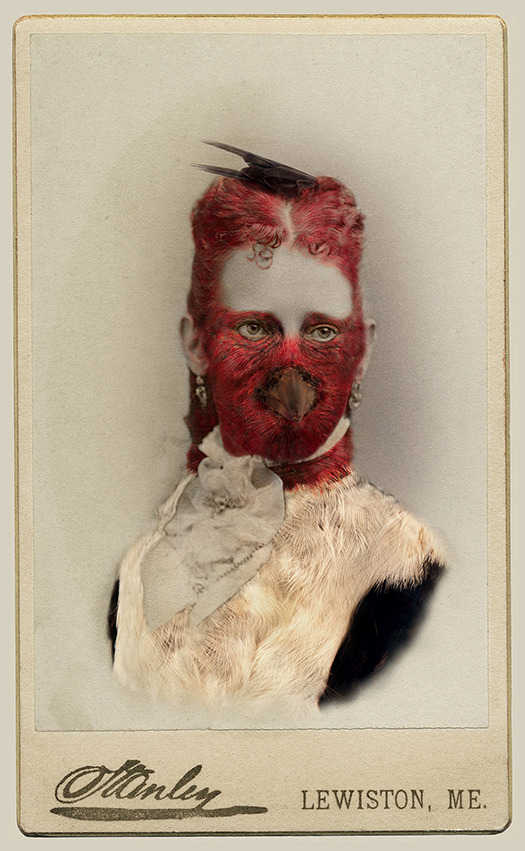

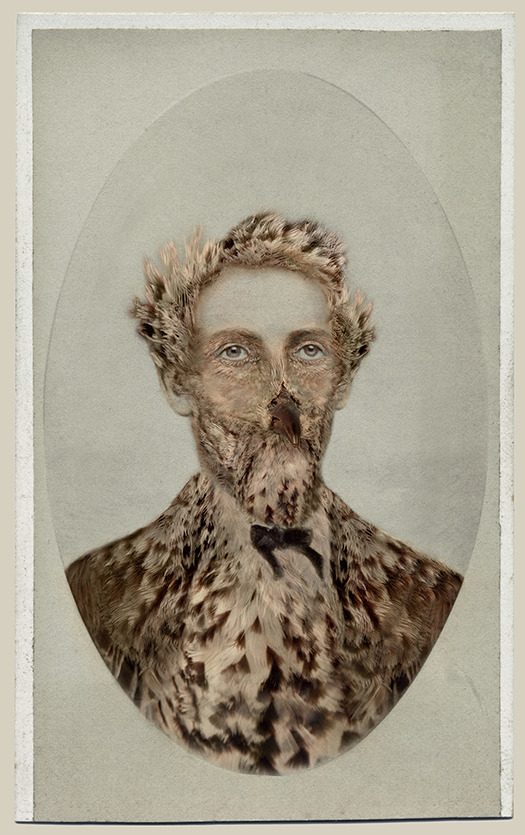

The large-scale photographs in Aviary combine many themes in nineteenth century society. Angelucci has breathed a curious new life in the Victorian cartes-de-viste, where she has melded heads of endangered or extinct birds to human bodies. Why birds? The photographer notes that her photographs are “hybrid crossovers of faith in science with a belief in otherworldly beings.” All of these birds were once plentiful during the late nineteenth century, and Angelucci’s humanizing of these delicate creatures is as much about respecting the earth and its creatures as it is about art.

All images are copyright © Sara Angelucci

Aviary (Barn Owl/endangered), 2013

C-print, 22 x 33.5 inches

Aviary (Northern Bobwhites/endangered), 2013

C-print, 34 x 49 inches

Aviary (Eskimo Curlew/extinct), 2013

C-print, 22 x 33.5 inches

Aviary (Female Passenger Pigeon/extinct), 2013

C-print, 26 x 38 inches

Aviary (Male Passenger Pigeon/extinct), 2013

C-print, 26 x 38 inches

Aviary (Heath Hen/extirpated), 2013

C-print, 22 x 33.5 inches

Aviary (Loggerhead Shrike/endangered), 2013

C-print, 22 x 33.5 inches

Aviary (Red-headed Woodpecker/endangered), 2013

C-print, 22 x 33.5 inches

Aviary (Sage Thrasher/endangered), 2013

C-print, 22 x 33.5 inches

Aviary (Short-eared Owl/endangered), 2013

C-print, 22 x 33.5 inches

Aviary (Spotted Owl/endangered), 2013

C-print, 22 x 33.5 inches

Aviary (Western Screech-Owl/endangered), 2013

C-print, 22 x 33.5 inches

Aviary (Winter Bobolink/endangered), 2013

C-print, 22 x 33.5 inches

Installation view of Aviary

Art Gallery of York University (Cheryl O'Brien, photographer)

Installation view of Aviary

Art Gallery of York University (Cheryl O'Brien, photographer)

Installation view of Aviary

Art Gallery of York University (Cheryl O'Brien, photographer)

Installation view of Aviary

Art Gallery of York University (Cheryl O'Brien, photographer)