We spoke fairly often in the years before he died on June 26, 2020 (the day Milton Glaser turned 91 years old). Whenever I’d ask “how do you feel?” Glaser responded with a minor moan punctuated by a faux Bronx intonation: “My mind is great, but my body is falling apart.” Then before I could complain about my own bodily aches and pains, he abruptly changed the subject from personal health to the state of politics, which seemed easier for him to stomach than his liver problems. However, he was even more interested in talking about the various projects he had going at the same time. His precarious health and frequent emergency hospital visits (as well as a longer than expected stay in rehab when Covid-19 hit in March, ultimately leading to his death in late June) delayed much of his work, but he was determined not to let degenerative organs and deteriorating muscles deprive him of making art, conceiving initiatives, and producing books.

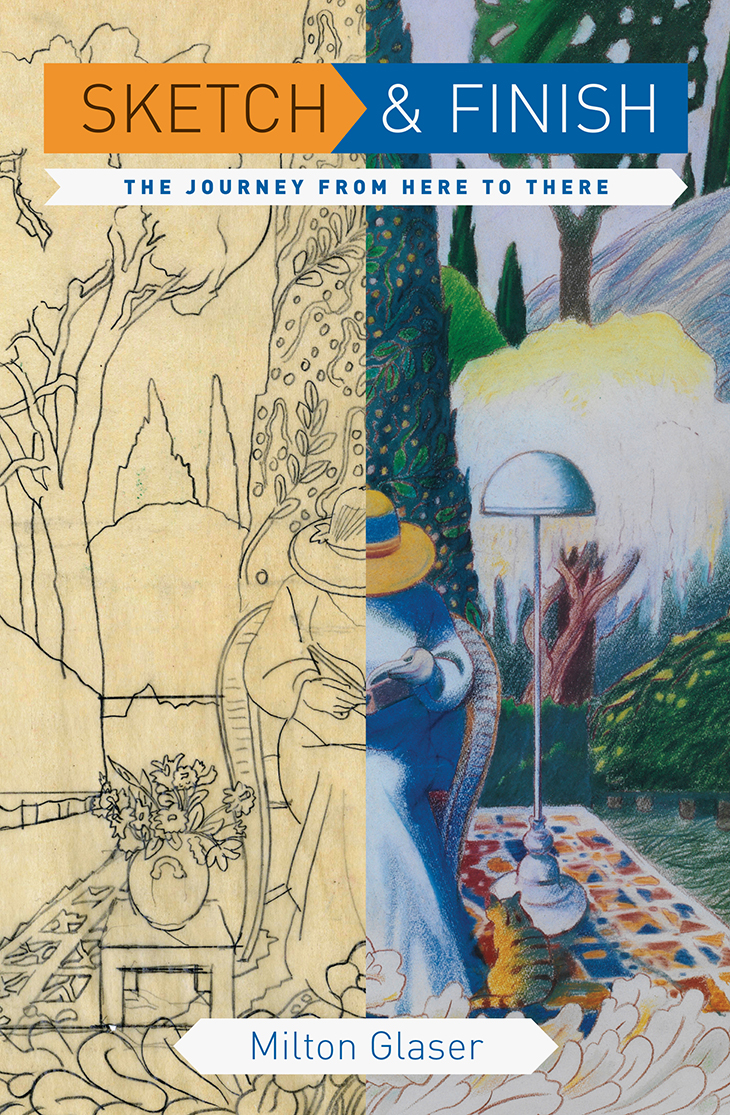

What I call Milton’s Miracle were the many times that he bounced back from the abyss to complete something unfinished. Less than a year before he sadly bounced no more, Glaser contracted for at least two books. Sketch & Finish: The Journey From Here to There (Princeton Architectural Press, 2020) is the first of Glaser’s posthumous volumes. Although I knew it was in the works, I was nonetheless surprised to receive a copy published so quickly during the current pandemic when so many publishing plans are still on hold. It boosted my spirits on many levels too. It’s a good book.

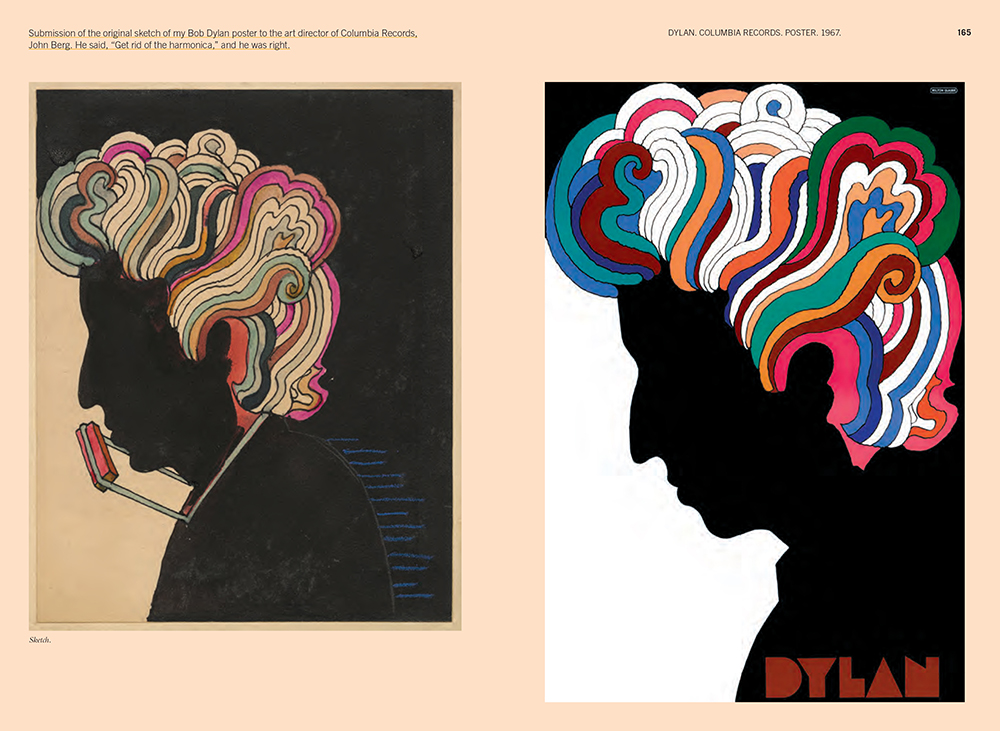

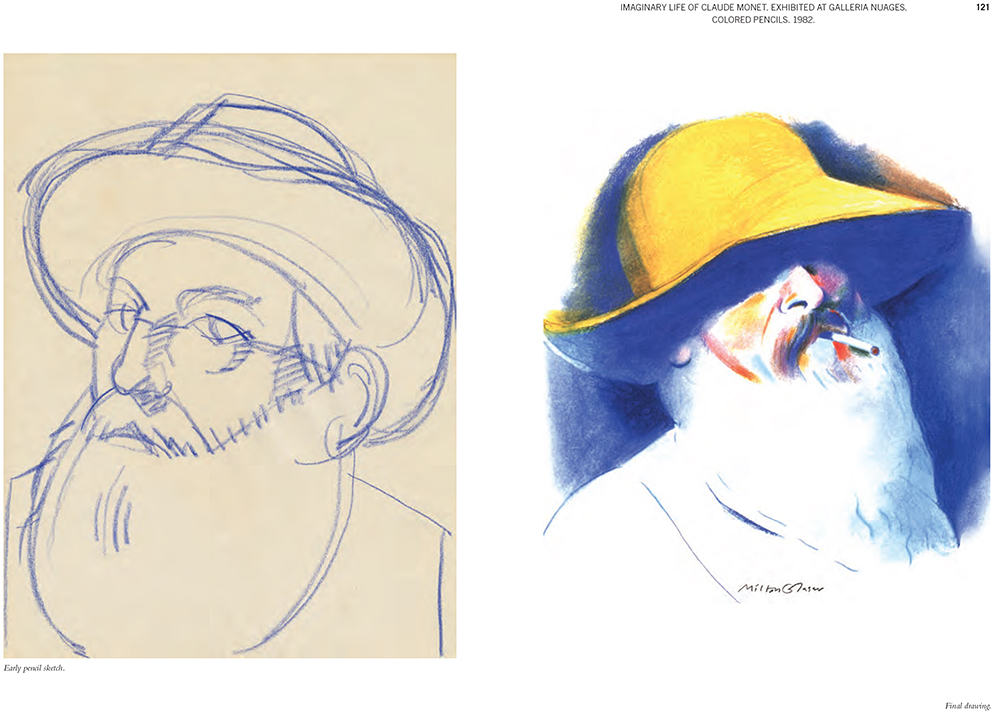

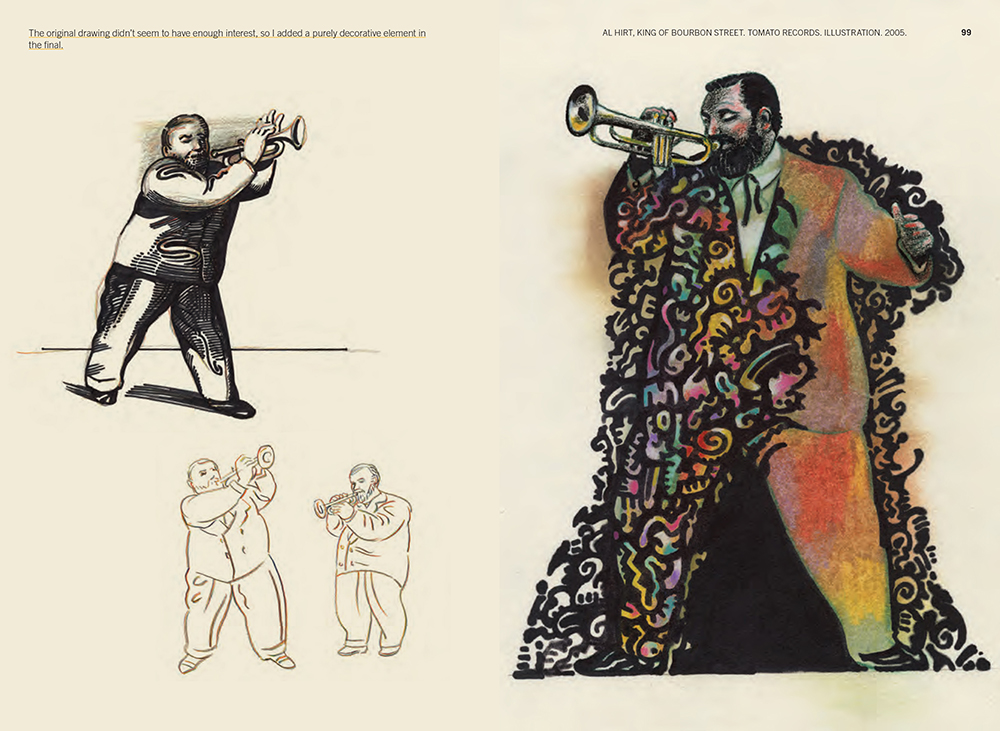

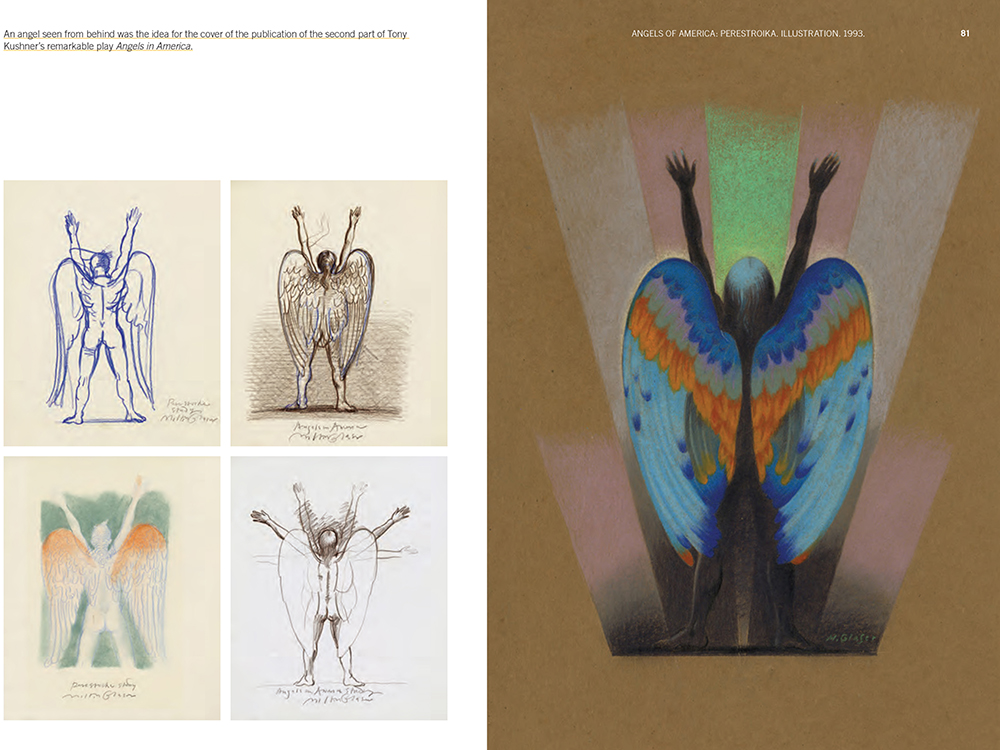

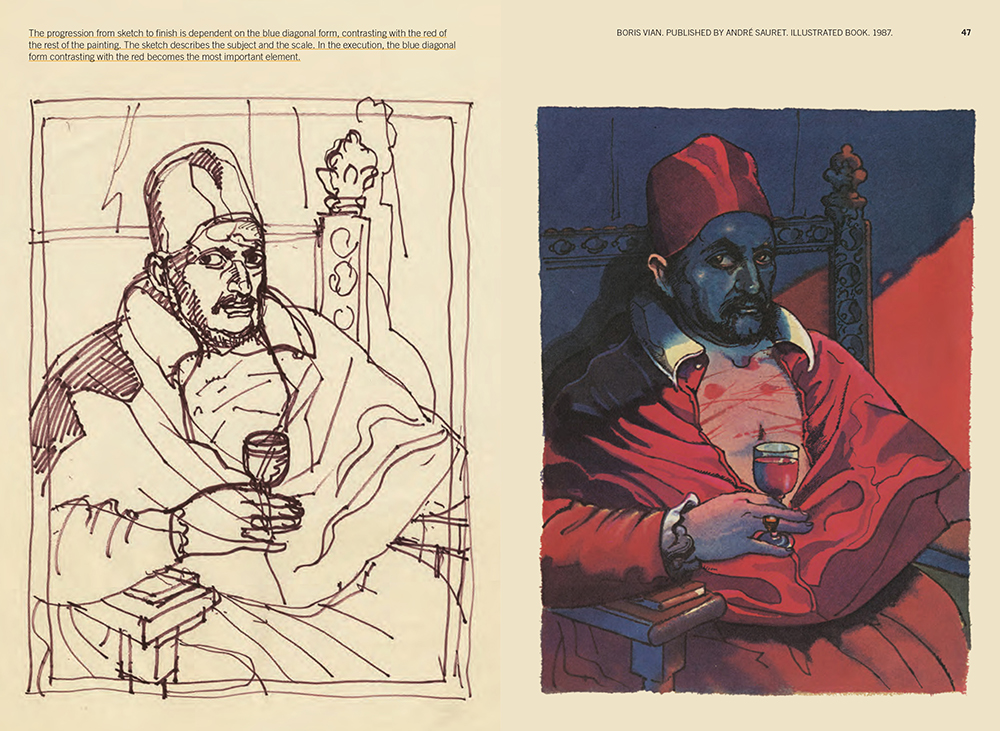

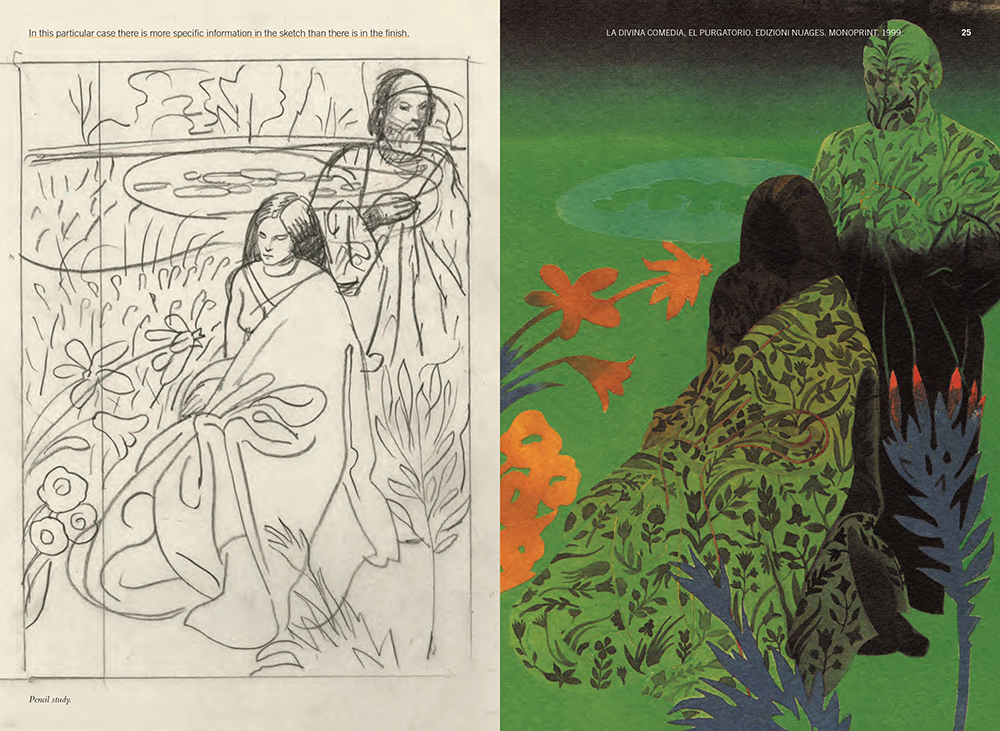

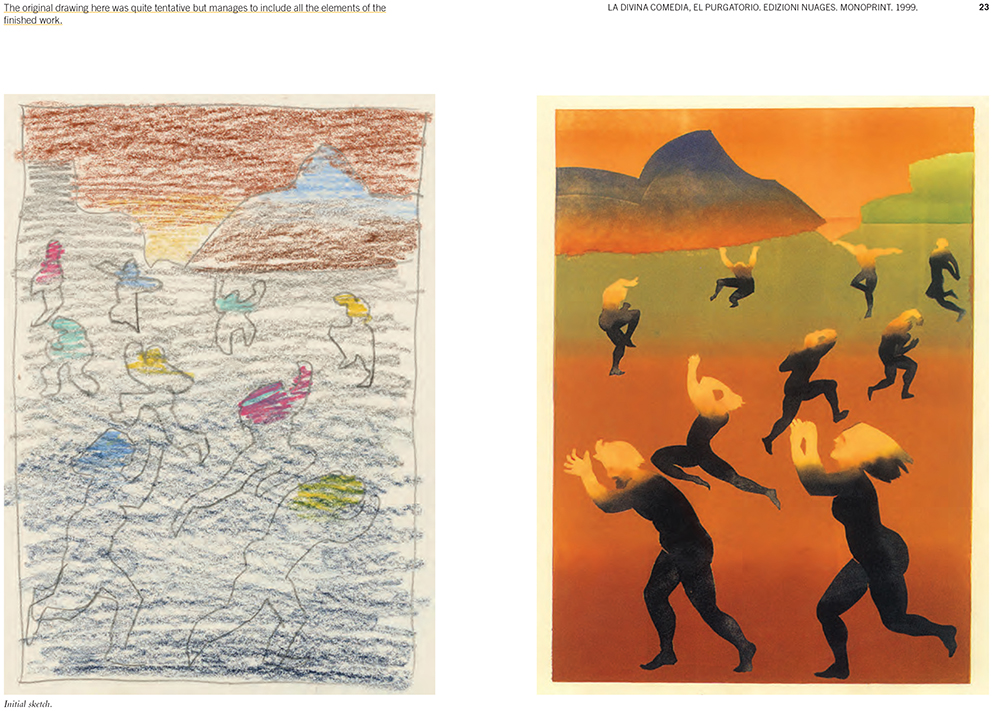

You might say, Sketch & Finish is an album of Glaser’s greatest hits but it is much more than the hits and a couple of misses (there are a couple where the sketch is better than the finish but I will refrain from pointing them out; you should find them for yourselves). The book illustrates Glaser’s teaching agenda, which is to say, one makes sketches to explore the unknown (the “tentative” nature of creativity) not to validate the existence of a predetermined outcome. As he states in his brief but spot-on introduction on the reason for sketching: “If you know the answer before you start, why bother?”

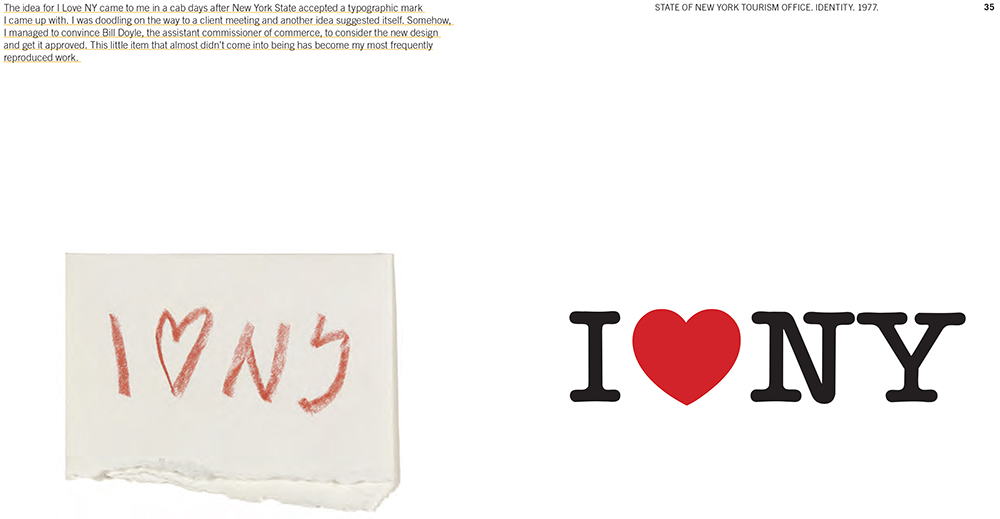

So, while the sketches selected here may indeed result in finished work, you can see the radical and nuanced shifts in attitude, aesthetics, and technique that occur throughout the process. Sometimes the transformation is significant, others imperceptible, and still others are doodles transformed. Glaser was such an incredible drawer — and with so many approaches to rendering — that nothing goes to waste. He explains (with the help of writer Anne Quito) exactly how an inspiration turned into an intent or how an intention became a window for a speculation.

The book’s design (in collaboration with Ignacio Serrano) is essential to the engaging visual narrative. Juxtapositions allow the reader to vividly experience what was taking place at the time of creation and the connections between mind, eye, and hand. In short, this is a delight for anyone who revels in the reveal of the creative process. And, just for the record, for those of you who are hoping to find some greatest hits, Glaser did not disappoint. You’ll find his two most famous works, and one of these (I won’t say which) may truly surprise you.