Jessica Helfand|Thesis Book Project

January 3, 2016

Brienne Jones

[[Intro from JH and images TK]]

++++

Think of the last time you took a walk in a city park, let’s say Washington Square Park. Have you ever noticed those footpaths that diverge from the pavement, cutting across the lawn? While working on my thesis, I discovered that these things are known as “desire paths,” and in retrospect, desire paths feel like an apt metaphor for process behind my thesis. —BJ

JH: Could you talk a little about how you saw that translating to the printed page? Is the book itself a kind of journey for you?

BJ: I wouldn’t characterize the books per se as a journey. The word journey suggests that there is a beginning and an end, or a sequential progression, and it wasn’t my goal to make the books a linear reading experience. If the making of the projects themselves is an act of “surveying,” of exploring topics and methods, then the act of making the books was an act of mapping.

BJ: During my time at RISD, I did several projects about places. In general, I find “place” interesting—I thought about becoming an architect—and I valued being able to go to a location as a part of the research process. I did site-specific projects (e.g. signage experiments, interactive installations) and projects about places I’d visited in the past (e.g. a branding/mapping project about a site in Japan, a sound map of a park). However, as I got deeper into the thesis process, I began to do more projects on places in the news, based on my experience in Japan. Unlike previous projects, I couldn’t actually travel to these places, so I had to rely on the Internet to get information. I became more and more interested in how this reliance might be shaping the projects, and began to use the technology directly in projects (i.e. making a project using Google Street View directly rather than grabbing screenshots to put together in another format).

Given that there were competing interests—developers, planners, politicians, the people living there—I was curious about what impression I, a third party, could “get” from afar about this situation. The most fascinating discovery came through a comparison of imagery from Google Street View and Bing’s Streetside. The collected screenshots of the same main street in Willets Point are starkly different between the two services—Google had years-old, pixelated images taken on a cloudy day, whereas Bing had newer, clearer shots taken on a sunny day. In Google’s set, Willets Point looked dark, blighted, and possibly dangerous; whereas in Bing’s set, Willets Point managed to look vibrant and interesting, possibly worthy of repair.

JH: Were there originally more that you rejected? And how did you narrow to three? I’d also like to hear more about the formal choices you made—type, composition, size—and how the writing itself evolved. In other words, let’s unpack your roles as author and maker a little …

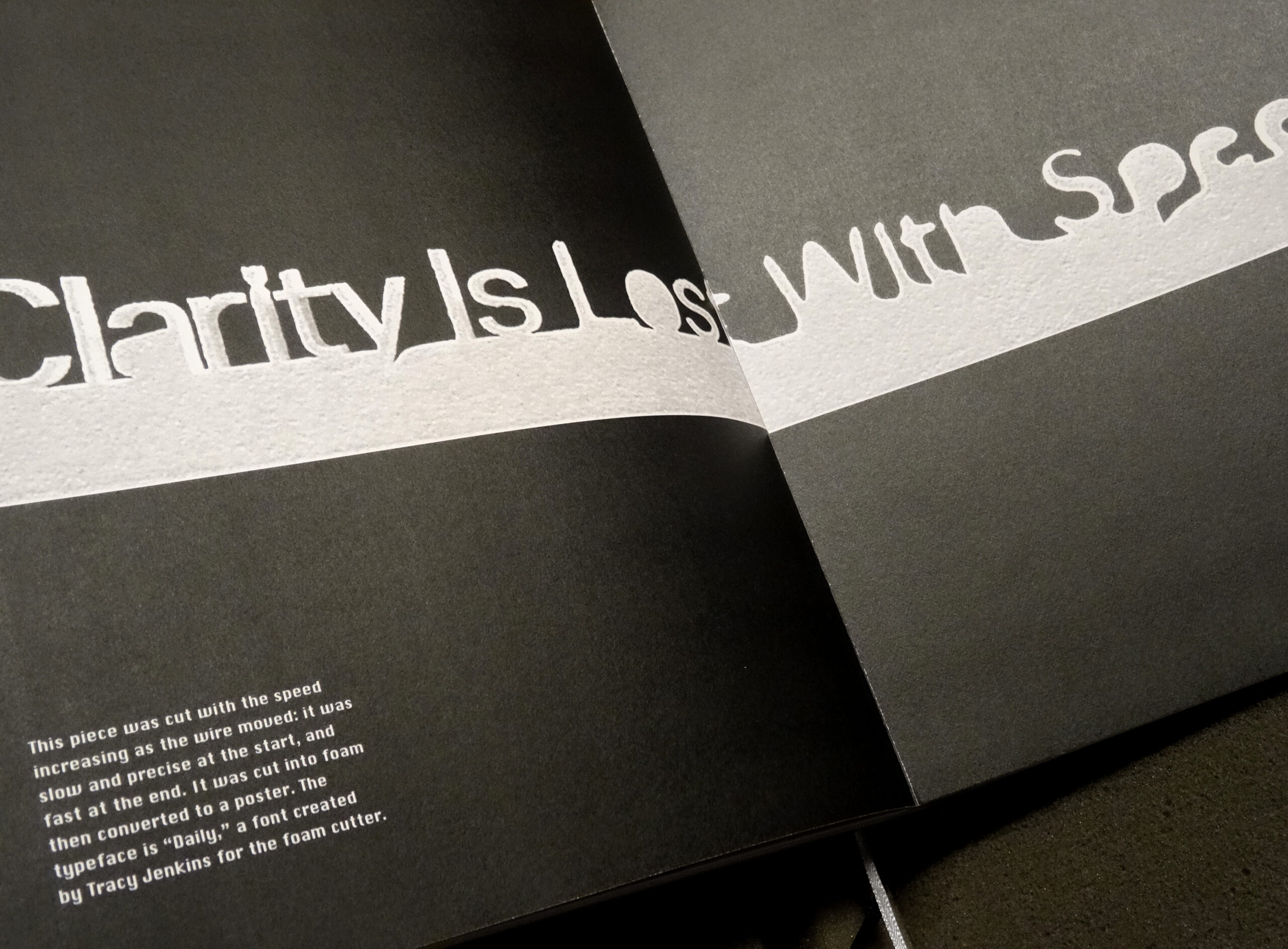

JB: Each of the projects explore the role of immersiveness, ambiguity, (counter-)intuitiveness, and language in an effort to create—and disrupt—interactions.

Part of the spark behind this work came from a difficult experience I had when I was in Japan in March 2011. The most succinct way I can put it is that, at the time, I felt as if I were inside a cocoon of misinformation; it was difficult to what I could glean from Japanese news, what I was being told from outside news sources, and my direct perception of a situation. The confusion created by these parallel yet disconnected narratives thus created a truly personal sense of urgency, a sense that designers, as creators of digital artifacts, should be critical of the digital context in which they are working.

Finally, as for the form of the book itself, it came about in response to having to put all of this moving, physical stuff—sometimes websites or app ideas, sometimes large-scale sculptures—into a book format.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Jessica Helfand

Related Posts

Recent Posts

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran A quieter place: Sound designer Eddie Gandelman on composing a future that allows us to hear ourselves think It’s Not Easy Bein’ Green: ‘Wicked’ spells for struggle and solidarity Making Space: Jon M. Chu on Designing Your Own PathRelated Posts

Jessica Helfand, a founding editor of Design Observer, is an award-winning graphic designer and writer and a former contributing editor and columnist for Print, Communications Arts and Eye magazines. A member of the Alliance Graphique Internationale and a recent laureate of the Art Director’s Hall of Fame, Helfand received her B.A. and her M.F.A. from Yale University where she has taught since 1994.

Jessica Helfand, a founding editor of Design Observer, is an award-winning graphic designer and writer and a former contributing editor and columnist for Print, Communications Arts and Eye magazines. A member of the Alliance Graphique Internationale and a recent laureate of the Art Director’s Hall of Fame, Helfand received her B.A. and her M.F.A. from Yale University where she has taught since 1994.