October 4, 2018

Chain Letters: Sean Adams

This interview is part of an ongoing Design Observer series, Chain Letters, in which we ask leading design minds a few burning questions—and so do their peers, for a year-long conversation about the state of the industry.

October is archives month, and to celebrate we’re looking at design history through a few key questions. A tall order, we know. Luckily we’ve tapped the best design practitioners and historians from across the globe to tackle it—and to ask each other questions of their own.

Sean Adams is the Acting Chair of the Graphic Design Program at ArtCenter. He also serves as Executive Director of the Graphic Design Graduate Program. Adams continues his design practice with The Office of Sean Adams. He is the author of eight books about design and design histroy, and on-screen author for LinkedIn Learning. He is the only two-term AIGA national president in AIGA’s 100-year history. In 2014, Adams was awarded the AIGA Medal, the highest honor in the profession. He currently is on the editorial board and writes for Design Observer.

Adams is an AIGA and Aspen Design Fellow. He has been widely recognized by every major competition and publication, including a solo exhibition at SFMOMA. Adams has been cited as one of the forty most important people shaping design internationally, and one of the top ten influential designers in the United States. Previously, Adams was a founding partner of AdamsMorioka.

Images from Adam’s forthcoming book: The Designer’s Dictionary of Type

There’s a well-known phrase attributed to Winston Churchill that says, “history is written by the victors.” Is this applicable to our understanding of design history? What’s being done to rewrite it?

I’ve repeated that quote to young designers and students for years. The point here, regarding design history, is about documentation. It isn’t that there are victors and a losing side. In design, if the work is not documented and disseminated, it disappears.

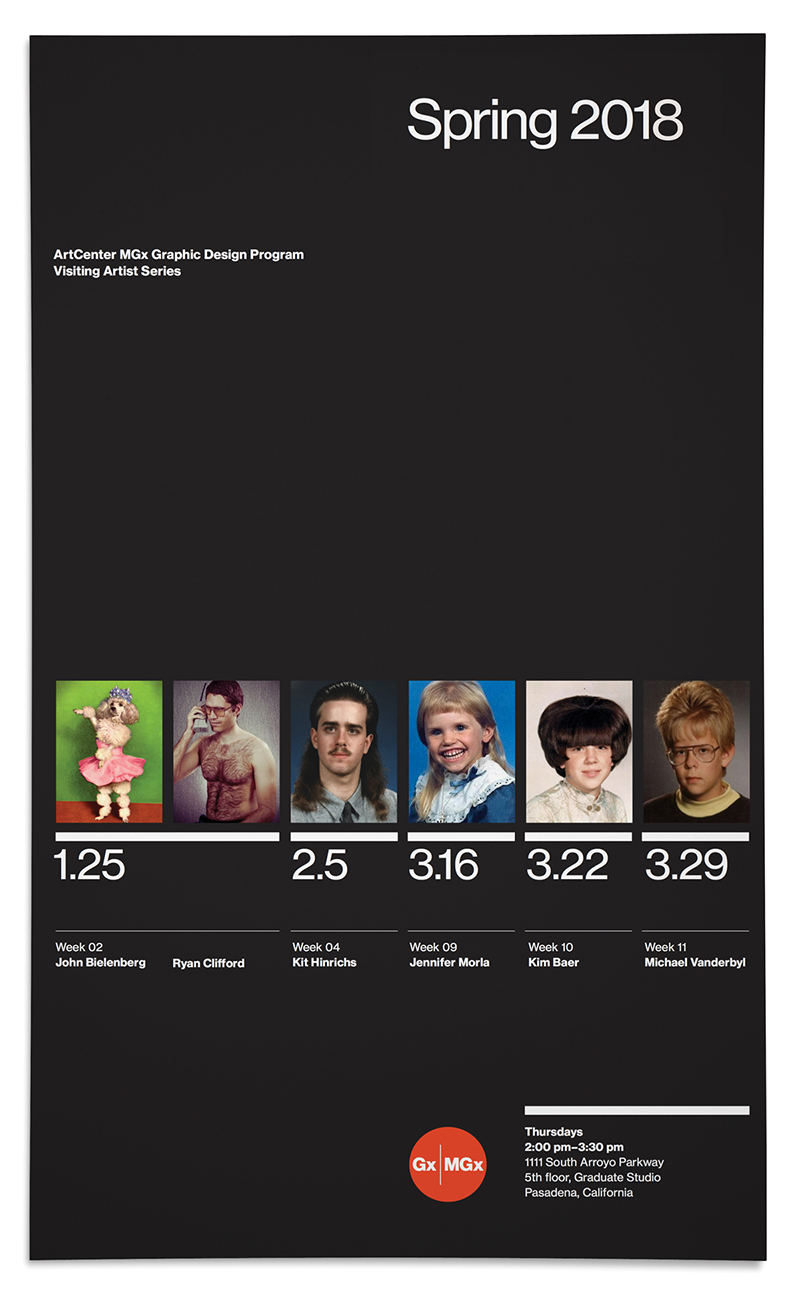

ArtCenter Lecture poster by Sean Adams

I have a friend who is a fantastic designer with a unique vision. I’ve repeatedly asked this person for work to publish in a book or article, but he sees maintaining a substantial archive of his work with well-photographed and good resolution images as beneath him. Each time I ask he claims, “I’m not interested in self-promotion. I shouldn’t need that to be recognized.” Unfortunately, I have deadlines, and I move on to another designer whom I know will have projects ready for publication. However, he is the same person who complains that the same designers are represented all the time. For years he insisted I was a media whore just because I had a 300 dpi image ready to go when asked. Wait, maybe this guy is not a friend.

The point regarding design history is about documentation. If the work is not documented and disseminated, it disappears. I had a friend who insisted I was a media whore just because I had a 300 dpi image ready to go when asked. Wait, maybe this guy is not a friend.

In looking back at historical works, can—or should—the quality of the design itself ever be separated from its context?

No, design is a product of its time, place, and designer. We live in a culture obsessed with a flawed concept of Darwinian evolution; that each year, a product will be improved, getting better. But evolution doesn’t work that way. It also is a response to time and place. The leg worked better than the fin when fish started marching about the riverbank. We can’t say a poster by Herbert Matter in 1936 is less successful than one designed today.

1936 poster by Herbert Matter

Understanding the culture, socio-economic conditions, and geopolitical issues of the time allow us to see the Matter poster as a remarkably original response to circumstances that led to World War I, technological advances in printing and photography, and pre-war Europe.

What is your strategy for weaving design history into your work?

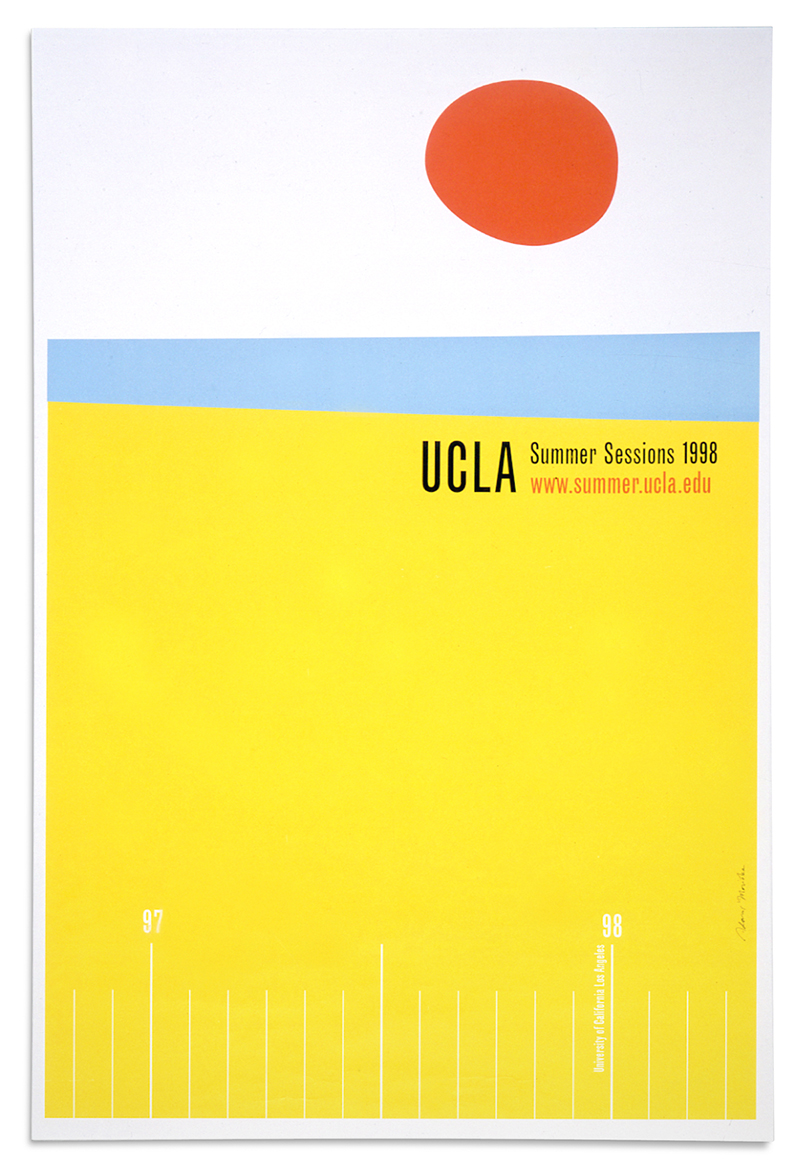

I don’t overtly weave design history into my work, but I am definitely aware of it. Years ago, I was asked why my work at the time had a mid-century look. It wasn’t because I was desperately appropriating everything fifties. The connection had more to do with a philosophy of optimism, clarity, design making the world a better place, and rejection of the world as convoluted, dystopian, and chaotic. My values matched the values of designers in post-war America. The formal and conceptual solutions were, then, similar. I also have a thing for seafoam and pink.

A 1998 UCLAExtension poster by Sean Adams

Name a designer from the past that people may not know about (but should look up right now).

Barbara Stauffacher Solomon: genius.

From Margaret Gould Stewart: Design can change the course of history. What are your picks for designs that altered events, in good and bad ways, and what can we learn from these examples?

Design, society, and technology are so tightly connected that it’s difficult to separate design as a discrete cause of change. The movable type press led to the Guttenberg Bible and launched the renaissance, but if Guttenberg typeset the book differently would we all be wearing silver jumpsuits today? There is the flawed design of the ballot for the 2000 election leading to an election crisis. But that was only one component in a multi-layered sequence of events.

In 1968, Memphis sanitation workers went on strike after two workers were killed by a garbage truck. Based on a graphic produced by the abolitionist movement in the 1850s with the text “Am I Not a Man and A Brother”, the striking workers produced posters stating “I Am a Man.” This poster powerfully and clearly articulated the rights of all people to be treated with dignity. The strength and simplicity of the graphic worked with low resolution newspaper and television coverage spreading the message nationally and adding influence for the civil rights movement.

Next week, Sean asks author and illustrator Nora Krug: The most dominant sense I have when I visit Berlin is the enormous weight of its history, specifically the Holocaust. It surrounds you but is unspoken; an issue filled with landmines often found easier not to discuss rather than address directly. Why was it important to tackle this part of history head-on, by putting your own skin in the game and sharing your family’s experience as visual memoir?

York Theater poster by Sean Adams

Observed

View all

Observed

By Lilly Smith

Related Posts

Design Juice

Rachel Paese|Interviews

A quieter place: Sound designer Eddie Gandelman on composing a future that allows us to hear ourselves think

Design of Business | Business of Design

Ellen McGirt|Audio

Making Space: Jon M. Chu on Designing Your Own Path

Design Juice

Delaney Rebernik|Interviews

Runway modeler: Airport architect Sameedha Mahajan on sending ever-more people skyward

Sustainability

Delaney Rebernik|Books

Head in the boughs: ‘Designed Forests’ author Dan Handel on the interspecies influences that shape our thickety relationship with nature

Recent Posts

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience Love Letter to a Garden and 20 years of Design Matters with Debbie Millman ‘The conscience of this country’: How filmmakers are documenting resistance in the age of censorship Redesigning the Spice Trade: Talking Turmeric and Tariffs with Diaspora Co.’s Sana Javeri KadriRelated Posts

Design Juice

Rachel Paese|Interviews

A quieter place: Sound designer Eddie Gandelman on composing a future that allows us to hear ourselves think

Design of Business | Business of Design

Ellen McGirt|Audio

Making Space: Jon M. Chu on Designing Your Own Path

Design Juice

Delaney Rebernik|Interviews

Runway modeler: Airport architect Sameedha Mahajan on sending ever-more people skyward

Sustainability

Delaney Rebernik|Books