October 1, 2015

Drawing It In

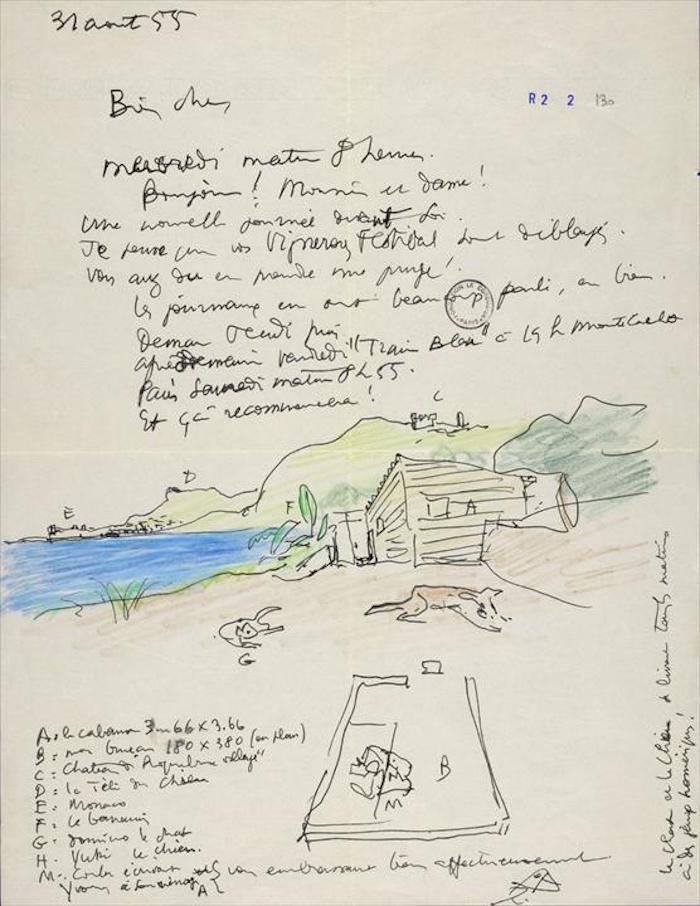

Drawing is the greatest means of communication for architects and designers with or without a brief. Getting ideas onto paper is another matter, but a foolproof strategy for designing does exist. When Le Corbusier “designed” hisCabanon in forty-five minutes, what exactly did he do? Did he scribble a complete building—plan, elevation, and section—onto the back of that proverbial envelope? Or was it just a doodle that was then deciphered and translated by assistants familiar with the master’s handwriting? We all know that a quick sketch can be either the beginning of a process or the end of it. It all depends on what you call designing. Does it happen only while actually working on paper or screen, or does a problem, brief, or project lodge itself inside of your head without your even knowing it’s there? And then come out, fully developed as a building, a painting, a chair, a lamp, or a book cover? For myself, I have identified five distinct strategies to start designing. (They apply to writing as well.)

1. AVOIDING

Need the car washed, emails answered, receipts filed? When the deadline already casts a long shadow on your conscience, you suddenly feel the urgent need to tidy up all those loose ends. You can sit down to work only when everything is tidy, in your mind and on your desk. I have to go through this phase every time. By now, I recognize it and use it to actually finish all those annoying little tasks that keep piling up.

2. THINKING

Our brain is an amazing tool—it works at the speed of light and is incredibly flexible. The problem is never lack of capacity but retrieval. We know it’s in there but cannot find it. Just sitting down (after having cleaned up the desk, of course) and putting your mind to a problem for a few minutes is an experience that we hardly ever allow ourselves to enjoy. If you avoidt emails, switch off the phone, keep your door, and the books on your desk closed, you’ll be surprised how quickly you start getting things sorted, in your head at least.

3. SKETCHING

After a few minutes of plain old pondering the issue at hand, it can be useful to start making marks on paper. Not necessarily proper mind maps or floor plans, but anything that will still be visible a day later. Picturing thoughts, even if you cannot draw at all, is truly effective, especially if you have to remember what you thought about a day later or communicate it to someone else. You can buy expensive drawing software, but I find that the time spent mastering a new application can be better applied to learning to sketch simple little drawings. Everybody—especially clients—loves a designer who can actually draw. As a type designer I am loath to admit that a picture does sometimes say more than a thousand words.

4. RESEARCHING

Knowledge is good, and looking around for signs of other intelligent solutions to a similar task may help. Gathering background facts also builds confidence and may help convince a client. Looking at too many annuals full of other people’s work can be dangerous, though: you either get totally discouraged because everybody else’s stuff looks so good, or you—inadvertently, of course—imitate something later, when you think you cannot recall anything you’ve seen.

5. COLLECTING

This is an ongoing activity. I do not know one designer, writer or architect who doesn’t keep things that are “interesting.” It doesn’t always have to amount to a complete collection of Braun hi-fi equipment from 1957 until today, as in my case, but anything that you could not throw away when you no longer needed it survived for a good reason: it spoke to you. If you can make your collection bring back that original inspiration, you can trigger parts of your brain that may have encountered the same problem before, even without knowing it at the time.

All these strategies work. One after the other, if not in the order mentioned above, but more often than not concurrently. We carry a design brief around with us all the time, not just during the hours we can charge a client. It just needs the right moment to manifest itself. That’s why Le Corbusier probably knew exactly what he wanted to do when he took out his pen. What these anecdotes fail to mention, however, is that after the first strike of genius, most of us have to spend much, much more time getting scribbles made into plans, ideas turned into prose, and proposals into commissions.

This article originally appeared in the April 2007 issue of Blueprint

Homepage image: A letter from Le Corbusier to his mother with a sketch of the Cabanon, 1955; ©FLC/ADAGP

Observed

View all

Observed

By Erik Spiekermann