July 1, 2010

Edward Koren in Retrospect

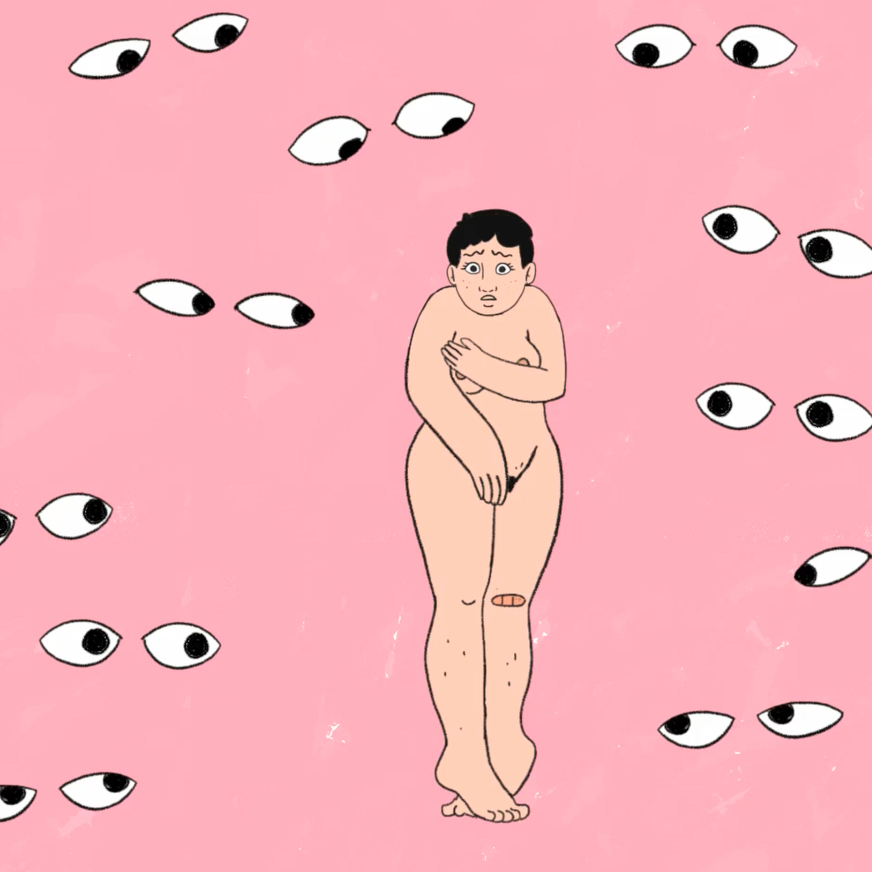

The expat life has its charms, but the downside is an endless longing for things not obtainable in the exotic land you inhabit. I’m talking here about M&Ms and peanut butter and the lengths to which one goes to find such American delicacies. In Budapest, where I lived in the late ’80s and early ’90s, that meant forking over $25 a week for an air-freighted copy of the Sunday New York Times more for the feel and the look of it than the content. And in London, where I lived after Hungary, it meant feasting on Edward Koren cartoons in my imported New Yorkers, which were as satisfying as corned beef sandwiches from Selfridge’s department store. Those whimsical, curly-haired folks with pointed noses and befuddled expressions — all rendered in Koren’s squiggly lines — spoke of home. Not exactly where I grew up on Long Island, but the world I knew about and aspired to, the Upper West Side, a neighborhood, as The New York Times put it recently in its review of a Koren retrospective, of “overeducated, comfortable but not superrich liberals and the psychotherapists who treat their garden-variety neuroses.”

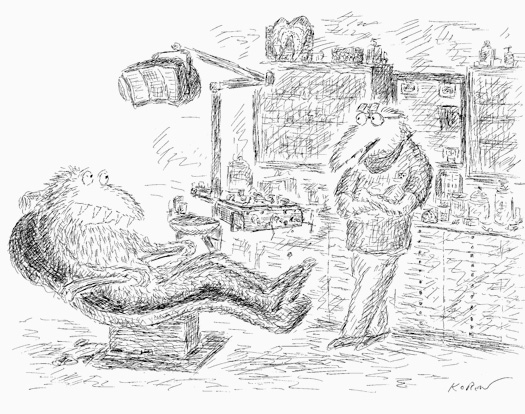

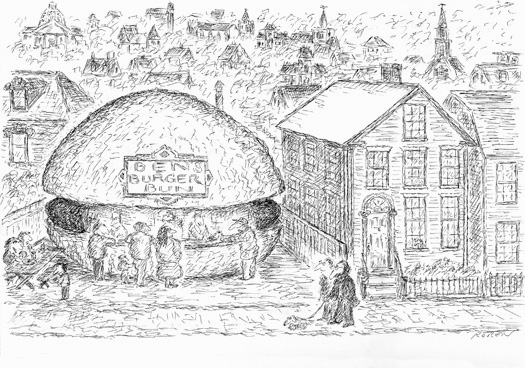

The exhibition, “Edward Koren: The Capricious Line,” took place at an appropriate venue: the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery at Columbia University, in the heart of the Upper West Side’s intellectual universe. (The show closed on June 12 but a lavishly illustrated catalog has just been published by the Wallach Art Gallery.) Koren, Columbia ’57, fits right in with his characters and their eternal quest to understand any number of perplexities: urban life, dentists, bicycles, machines, art and artists, and how city dwellers deal with the weirdness of the countryside at their weekend homes. It’s a world of fantasy “based firmly in reality,” notes David Rosand, in an exhibition essay, and one that is not only “psychologically acute” but also philosophically provocative, as the Times pointed out.

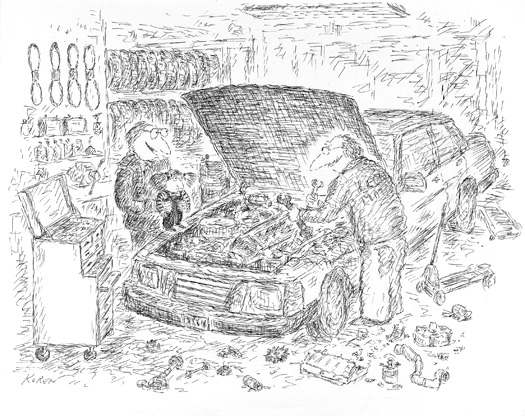

Koren’s work has appeared in The New Yorker consistently since 1962. As the Times review points out, the cartoons only vaguely allude to events happening outside of his narrow milieu — such as the AIDS crisis, several wars in the Middle East and racial strife. His “dopey creatures of indeterminate species,” and their human friends, aren’t concerned with much beyond their sphere, although they do address more existential issues, such as how things work: mysteries long plumbed by the strange, wondrous people who know how to build things. In Koren’s universe, a father with a baby watches a mechanic tinker with a car, and says, “I’d like my daughter to know something about engines.”

Talking with Feiffer, Koren said that much of his artwork and gag lines reflect his own well-developed “mistrust of authority,” a statement that makes sense when you see his characters being gently baffled by so many things, from an ATM machine in a tree to a restaurant in the shape of a hamburger in a country village. I find it less easy to make out the “fury and anger behind the images” that he also claims exists. What’s clear is that Koren’s audience probably starts at 59th Street and goes up to Morningside Heights. As the cartoonist acknowledged: “People in Vermont don’t have a clue about my work. There’s no resonance. It’s about class and a class-divided country. Humor is based on an unwritten understanding for effect.” That’s what I got about Koren, whether I was chuckling in London or Budapest or anywhere.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Ernest Beck

Recent Posts

Why scaling back on equity is more than risky — it’s economically irresponsible Beauty queenpin: ‘Deli Boys’ makeup head Nesrin Ismail on cosmetics as masks and mirrors Compassionate Design, Career Advice and Leaving 18F with Designer Ethan Marcotte Mine the $3.1T gap: Workplace gender equity is a growth imperative in an era of uncertainty

Ernest Beck is a New York-based freelance writer and editor.

Ernest Beck is a New York-based freelance writer and editor.