Jessica Helfand|Essays, The Ezra Winter Project

May 1, 2012

Ezra Winter Project: Chapter Five

If men at forty will be painting lakes

The ephemeral blues must merge for them in one,

The basic slate, the universal hue.

There is a substance in us that prevails.

Wallace Stevens

Le Monocle de Mon Oncle, Canto VI

1918

Part 5 : Stuyvesant 9290

In 1918 — the year of the Rietveld chair and the Spanish Flu pandemic, a woman called Marion Reynolds Slone commissioned Ezra Winter to make a painting for her Upper East Side residence.

Soon afterward, she rejected it, regretting that it didn’t harmonize with her curtains. Her chauffeur drove down to Winter’s studio on MacDougall Alley and returned it.

Fortunately, for Winter, there would be other private commissions — dining room murals for Lloyd Griscom, an American diplomat who briefly served as US Ambassador to Brazil and Italy, and for Libanus Todd, a successful businessman and inventor — both of whom befriended the artist and are likely to have directed him to more promising commissions.

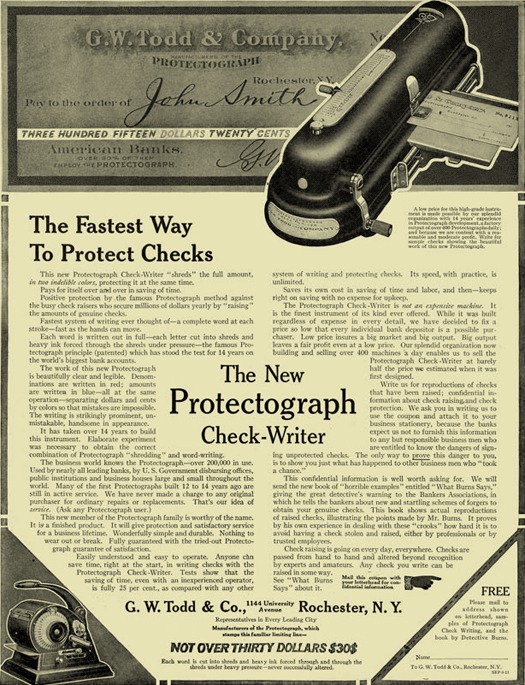

A bank executive and inventor, Libanus Todd was best known for inventing a check-writing machine. His son, an artist, kept a studio on the Todd estate in Rochester, and Winter often used it when he visited.

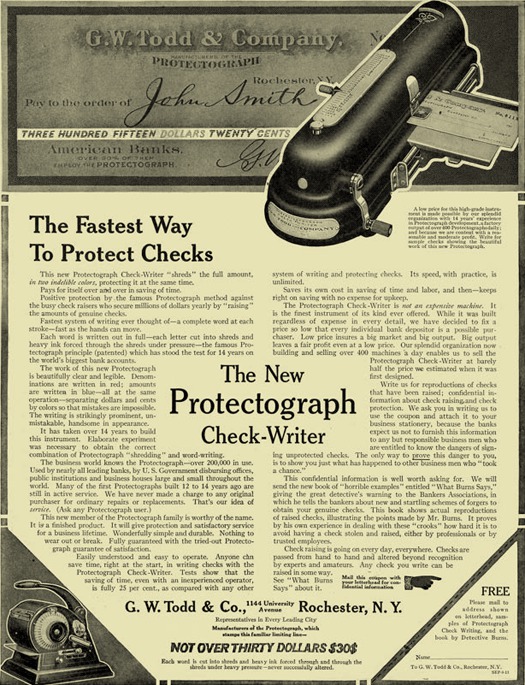

Lloyd Carpenter Griscom served as American Ambassador to Brazil and later, to Italy, where he probably met Ezra Winter. A practicing Quaker, Griscom played a central role in the relief effort following the 1908 Messina earthquake, and was a strong advocate for free trade.

A year after the earthquake, the Wright brothers traveled to Rome to provide flight training for two Italian lieutenants. Griscom (to the right of the derrick, in the long coat) was a passenger on at least one of the flights, and King Vittorio Emmanuel III (shown here, at left) was a spectator.

And then in 1920, Ezra embarks upon his first major public project: the dome of the main lobby of the Cunard Building in New York.

A hand-colored postcard of the Cunard Building at about the time Winter was hired

The most costly building ever built in the United States — 13 million dollars, 21 stories and over 700,000 square feet — the Cunard Building was erected on a historic plot that claimed to be the original homestead of the city’s first white inhabitants. In the early 19th century, the original Delmonico’s was also sited there.

Delmonico’s on Beaver and William Streets, about 1895. Photograph by Robert L. Bracklow (1849–1919). From the Collections of the Museum of the City of New York.

Cunard Building, New York, 1921. Photograph by Irving Underhill

Cunard Building, New York, 1921. Photograph by Irving Underhill

The grand foyer as it looked in the 1920s

Sharing the decorative tasks required by this extraordinary building were two other American Academy laureates: fellow muralist Barry Faulkner, who produced the maps of sea-routes for the walls and John Gregory, a sculptor, who did the bronze floor panels.

The Cunard murals — eight panels, four twenty-foot-high pendatives and four roundels, measuring nine feet in diameter — celebrated the romance of sea travel, with the great explorers (Columbus and Cabot, Drake and Ericson) all featured as the original seafaring pioneers. Featured, too, were their most notable marine achievements, including Sir Francis Drake’s Golden Hind (a fighting ship from the Spanish Armada, during the reign of Elizabeth I) as well as the escapades of Christopher Columbus, Sebastian Cabot, Leif Ericsson. (And no shortage of mermaids and mermen.) In the summer of 1921, the original sketches (Winter did them all in pastel) were exhibited at the Atlantic Yacht Club.

Detail of the Sebastian Cabot mural in the Cunard building

Ceiling detail, Cunard murals. Photograph by Johan van Lierop, 2011

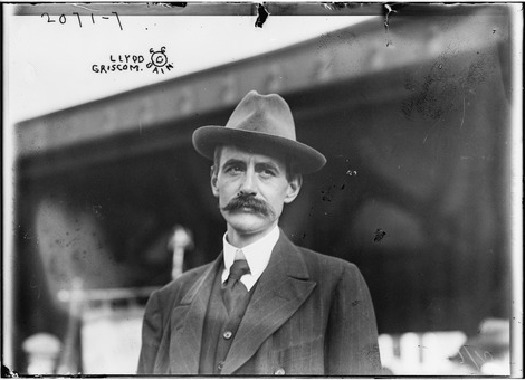

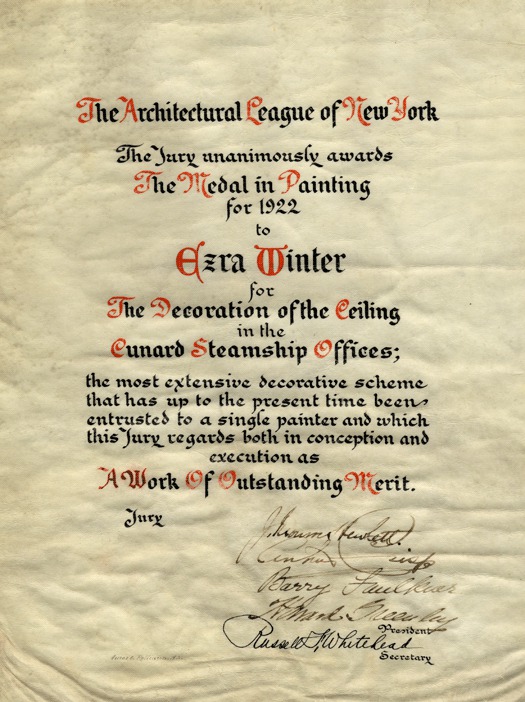

Winter was awarded the medal in painting for the Cunard murals from the New York Architectural League in 1922. He was 36 years old.

Ezra Winter’s medal citation

Two subsequent commissions for murals at the Rochester-based Eastman School of Music and Eastman Theater followed. The New York Times described the Eastman Theatre as “the most luxurious building as yet dedicated to screen drama” and went on to report that it held “the most modern system of hearting and lighting, the most notable chandelier, the handsomest mural paintings”. A series of four 12 x 21’ foot panels for the trading room ceiling at the New York Cotton Exchange were commissioned a year later, as were the ceiling and stained glass windows for the Strauss Building in Chicago.

Mural detail, Eastman School of Music, Rochester New York, 1922

Mural detail, Eastman School of Music, Rochester New York, 1922

By the mid-1920s, Winter was receiving significant attention for his unusually disciplined approach to painting in concert with the architecture. Reviewers everywhere praised his impeccable technique. “There is a unity established between the architecture, the sculptured ornament, and the paintings that is particularly worthy of notice, “ declared one reporter. Another noted the synthesis of architecture and surface decoration, noting that: “Too often in our modern buildings the decoration has been an afterthought, conceived and executed after the building was itself entirely completed.” Yet another critic referred to him, clearly gesturing to his immense talent for detail, as “an echo from the Renaissance”.

Though much of the work happened on site, Winter needed a proper space in which to work, and ended up in midtown Manhattan in unusually grand circumstances. There are two versions of this story: in his memoir Sketches from an Artist’s Life, Barry Faulkner recalled hearing about a “vast, empty attic” in Grand Central Station, while the other, more likely version claims that Faulkner and Winter each already knew the space, since it had been leased by the U.S. Shipping board for its camouflage artists after the war. Either way, they seized upon it — an empty loft space in the south end of the building — and divided it with a ten-foot wall of plywood to create two side-by-side studios.

By the time his divorce from Vera Beaudette was final in 1925, Ezra Winter was famous.

Ezra Winter, photographed in his Grand Central Station studio in 1922, at work on the murals for the Eastman Theatre

Private and spacious, the studio was ideally located in the center of everything. The two painters even had a telephone with a Manhattan exchange — Stuyvesant 9290 — a nod to the 17th-century land owner who played a prominent role in the early founding of New York. In the late 1930s, Peter Stuyvesant was satirized in the Broadway debut of Maxwell Anderson and Kurt Weill’s Knickerbocker Holiday, where, in a role originated by Walter Huston (grandfather of Angelica), he sang September Song.

Oh the days dwindle down to a precious few,

September …

November …

And these few precious days I’ll spend with you

These precious days I’ll spend with you

September Song: music by Kurt Weill, lyrics by Maxwell Anderson. Film footage courtesy Travel Film Archive

Time was indeed precious for Winter, who wasted no time getting his studio up and running, collaborating on a number of projects with Faulkner: to have a studio in Grand Central Station was nothing short of exotic, and it bears saying that the romantic location of the artists’ atelier would be widely reported in the national press for years to come. “After the armistice, when he took up mural painting, he found his studio in MacDougall Alley too small for his large canvasses. So now he lives and works atop one of the country’s largest train terminals,” noted Richard Massock in a 1929 issue of The Decatur Review. Deming Seymour, a gossip columnist for the Greeley, Colorado Tribune-Republican, later described the illuminated constellations that cover the terminal’s dome. “Up somewhere above this panorama of the heavens are the studios … to reach them, one goes as high as the elevators rise, them climbs a stair and follows a board walk through a maze of pipes and girders to the doors …”

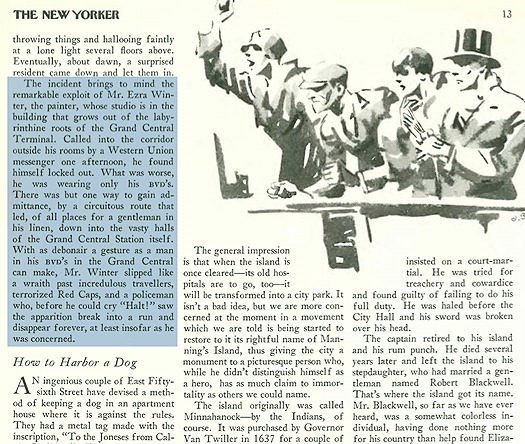

Most notably, in January of 1928, Winter was briefly locked out of his studio when summoned by a telegram. Dressed only in his underwear, the incident was duly reported in The New Yorker’s Talk of the Town column the following week, where he was referred to as “a gentleman in his linen”.

The New Yorker, January 21, 1928

Yet in spite the accolades pouring in, Winter becomes enraged when a 1922 article in The World reviews the Cunard murals but fails to, in the words of one of its editors, “say it with flowers”. In a subsequent edition, Winter’s letter is published in full. “Either your critic is so ignorant of what he is writing about that he should be put at the foot of his class,” seethes Winter, “or he is malicious enough to deserve the worst.”

Such a comparatively minor — yet pernicious — moment of vitriol offers a critical cue into the artist’s emerging psyche. Mural painting (an arguably Byzantine art form in what was, at the time, a newly-modern world) was by all accounts flourishing, and Winter was riding the wave: he was well-respected, well-paid, and well on his way to enormous success. Not yet 40, he had established himself as a working artist in one of the greatest cities in the world — yet the slightest tone of diminished praise enrages him deeply. Winter’s public rebuttal reveals a palpable sense of moral indignation, but his fury is transparent. It is not anger that he is fighting. It is terror.

Was he afraid of being outed as a self-taught farm boy, or did he suspect that he was working on borrowed time? Were hovering financial obligations to blame for his worries, or was fear of failure at the root of his malaise? Could the review in The World have served to momentarily reignite the same sense of worthlessness that had likely festered in the last years of his marriage to the hot-headed Vera? While all are indeed possible, it is also true that if there was a substance in Winter that endured, he found it in his work. It is painting that sustained him intellectually and creatively; painting that provided him with a kind of dazzling social currency; and painting that ultimately nourished him spiritually as well. As long as he was making the biggest, grandest pictures anyone could imagine, Ezra Winter would prevail.

The ensuing decade would find the artist engaged in drama-infused love affairs and sailing to the Antarctic, throwing wild parties in his atelier and teaching graduate students at Yale. He would continue to work, juggling commissions from New York to Birmingham, Chicago to Washington. He was handsome and famous and rich, but none of it would ever be enough, because no matter what he did or didn’t do, no matter where he went or who he was with, he was — and would always be — fundamentally alone. The ephemeral blues had begun.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Jessica Helfand

Related Posts

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

The Observatory

Ellen McGirt|Books

Parable of the Redesigner

Arts + Culture

Jessica Helfand|Essays

Véronique Vienne : A Remembrance

Recent Posts

Mine the $3.1T gap: Workplace gender equity is a growth imperative in an era of uncertainty A new alphabet for a shared lived experience Love Letter to a Garden and 20 years of Design Matters with Debbie Millman ‘The conscience of this country’: How filmmakers are documenting resistance in the age of censorshipRelated Posts

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

The Observatory

Ellen McGirt|Books

Parable of the Redesigner

Arts + Culture

Jessica Helfand|Essays

Jessica Helfand, a founding editor of Design Observer, is an award-winning graphic designer and writer and a former contributing editor and columnist for Print, Communications Arts and Eye magazines. A member of the Alliance Graphique Internationale and a recent laureate of the Art Director’s Hall of Fame, Helfand received her B.A. and her M.F.A. from Yale University where she has taught since 1994.

Jessica Helfand, a founding editor of Design Observer, is an award-winning graphic designer and writer and a former contributing editor and columnist for Print, Communications Arts and Eye magazines. A member of the Alliance Graphique Internationale and a recent laureate of the Art Director’s Hall of Fame, Helfand received her B.A. and her M.F.A. from Yale University where she has taught since 1994.