Fairy Tale Architecture

Fairy tales have transfixed readers for thousands of years, and for many reasons; one of the most compelling is the promise of a magical home. How many architects, young and old, have been inspired by a hero or heroine who must imagine new realms and new spaces — new ways of being in this strange world?

In this series on Places, participating firms have produced works exploring the intimate relationship between the domestic structures of fairy tales and the imaginative realm of architecture.

Houses in fairy tales are never just houses; they always contain secrets and dreams. This project presents a new path of inquiry, a new line of flight into architecture as a fantastic, literary realm of becoming. We welcome you to these fairy-tale places.

— Kate Bernheimer & Andrew Bernheimer

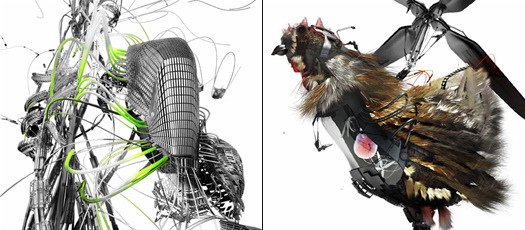

Baba Yaga is one of the most impressive figures in Russian folklore. An old woman with witch-like powers, she flies in a huge mortar, using the the pestle as a rudder, or sometimes on a broomstick. Sometimes she kidnaps children — or, lost in the woods or great field, they come upon her hut and never return home. One can hardly think of Baba Yaga without envisioning her spectacular hut. In folklore, it is often adorned with bones and little skulls. Standing on chicken legs, it spins when she is angry.

I smell the blood of an Englishman.

Be he ‘live, or be he dead,

I’ll grind his bones to make my bread.

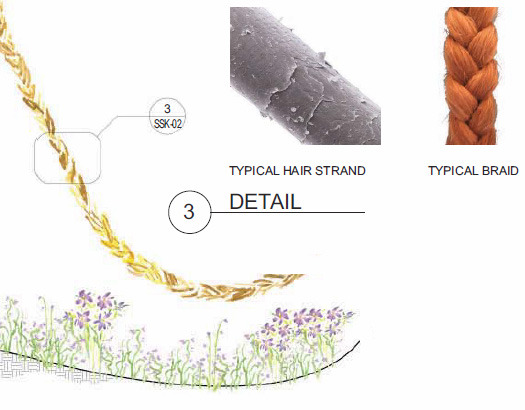

“Rapunzel, Rapunzel, let down your hair,”

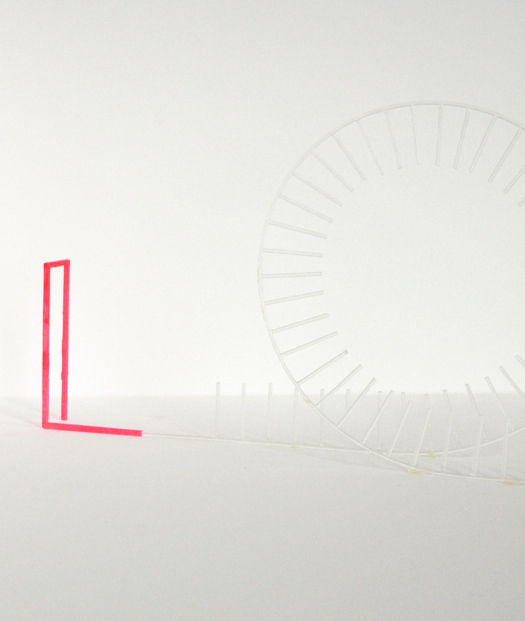

Rapunzel’s tower has come to symbolize both an enchanted, magical home and a dreadful prison from which to escape. Inside, one’s heart is full of desire and longing; and one must always also get out. The complicated emotional valence of this space is part of its longstanding appeal.

“Snowflake,” an iconic Russian fairy tale. Its cold end is sublime. One of my favorite renditions is in Andrew Lang’s Pink Fairy Book, and begins with a childless couple. They love children. They are lonely. They watch the neighborhood children play in the street during a snowstorm and decide to go out and play too. Why not? They are not in an amused mood but perhaps this will help, they think. They decide to build a snow child. “No use making a woman,” the wife (Marie) inscrutably says.

Spring arrives and Snowflake gets sad. Marie is quite worried. Worry blizzards this story from beginning to end. “What is the matter, dear child?” asks her mother. “Why are you so sad? Are you ill? Or have they treated you unkindly?” Snowflake tells her mother that she is well. Yet the child is sadder with each passing day — as the birds sing louder and louder and the flowers burst in the fields.

Many readers cannot bear the unrelenting sadness of this short fairy tale by Danish author Hans Christian Andersen. It has a spare and harrowing plot. A young girl is sent out by her impoverished parents to sell matches on the last evening of the year. She is barefoot, for she has lost her slippers; one has simply gone missing, and the other is stolen by a boy who says he will use it as a cradle for his own future children.

A Monkey King born from a stone can transform into 72 other things: bug, bird, beast of prey, tree and so forth. As such, he is his own Trojan Horse — he can sneak into anything, anywhere, right into the belly of an enemy and destroy him from the inside out. He travels 180,000 miles as a cloud in one crazy loop! He’s a bird, he’s a plane — even Superman can’t do all the things the Monkey King can do.

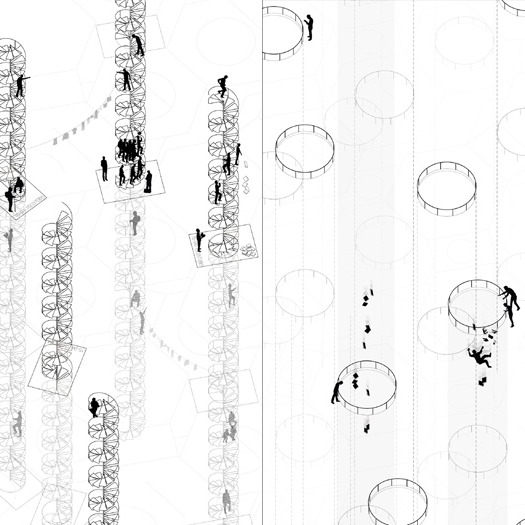

This dense, nine-page story concerns a library that houses all of the books ever written and yet to be written. The Library is arranged non-hierarchically; all of the volumes — from the most rudimentary to the most inscrutable — are equally important in this infinite space. Its rooms are hexagons. Its staircases are broken. The Library’s many visitors — elated, dogmatic and anguished types are all represented — strangle one another in the corridors. They fall down air shafts and perish. They weep, or go mad. Desperate characters hide in the bathrooms, “rattling metal disks inside dice cups,” hoping to mind-read the call number for a missing canonical text. Others, overcome with “hygienic, ascetic rage,” stand before entire walls of books, denouncing the volumes, raising their fists.

Why the Sun and Moon Live in the Sky

This children’s tale introduces the sun and his good friend, water. The sun visits the water often, but the water never visits the sun. The sun — who seems sad — asks him why; and the water says, “Well, if you want me to visit you, you’ll have to build me a very big house.” So the sun goes home to his wife, the moon, and tells her of the request. Apparently she approves, for the sun builds a very big house, and just as promised, the water visits, bringing along his friends, the water animals and fish and water people and so forth. Now water is knee-deep in the house, and he grows concerned, but the sun and moon assure him the house is still safe. Soon water fills the giant house to the brim, and the sun and moon climb up to the roof. Eventually the water covers pretty much everything up to the sky, where the sun and moon live today.

My mother, she slew me

My father, he ate me

My sister, Marlene,

Gathered my bones,

Tied them in silk,

For the juniper tree.

Tweet, tweet, what a fine bird am I!

Observed

View all

Observed

By Observed

Related Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

Recent Posts

Minefields and maternity leave: why I fight a system that shuts out women and caregivers Candace Parker & Michael C. Bush on Purpose, Leadership and Meeting the MomentCourtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packagingRelated Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays