January 24, 2018

Chain Letters: Sarah Doody

This interview is part of an ongoing Design Observer series, Chain Letters, in which we ask leading design minds a few burning questions—and so do their peers, for a year-long conversation about the state of the industry.

In January, we examine the intersection of design and tech.

Sarah Doody is a New York City-based user experience designer and founder of The UX Notebook, a weekly newsletter that helps people learn to think like a designer. She also has a series of online UX courses to help UX designers and their teams.

She works with clients to help them create products and experiences that are guided by research and 14 years of professional experience. Sarah is passionate about creating products that solve true problems, and not technology for the sake of technology. She is also very active in the UX community, speaking and conducting UX workshops worldwide.

Live with purpose street art Sarah found in Melbourne, Australia

With every passing year, technology becomes more seamlessly intertwined with the human experience. In your role, how have you seen this affect human behavior?

We are tethered to technology. The average adult spends four hours on their phone per day. That equates to five years over a lifetime. What are we doing? Everything. But the supposed increased access to information is actually limited, because targeting and algorithms actually give us more of the content we respond to. This is called a “filter bubble.” (Watch the TED Talk.) One thing that perpetuates this, I believe, is that people say a lot of things online that they wouldn’t say in person. When we’re given more of what we want, we fail to see other perspectives. And this creates a lot of division.

Facebook’s first President, Sean Parker (who also co-founded Napster), recently did an interview where he spoke about how some technology is intentionally designed to create experiences that become addictive. In the early years of Facebook, Parker says internal discussions included figuring out how the platform could “consume as much of your time and conscious attention as possible.” The constant social feedback loops are what keep us coming back, spending time, and contributing content to these platforms.

Loren Britcher, the designer who created the slot machine-type “pull to refresh” feature says, “I spent many hours, weeks, months, and years thinking about whether anything I’ve done has made a net positive impact on society or humanity at all.” I’m curious to see if we, as users, will enter a phase of recognizing the negative effects of technology on our relationships and brains, and be more thoughtful about when, why, and how we engage with technology.

When we’re given more of what we want, we fail to see other perspectives. And this creates a lot of division.

What is a new challenge UX designers will have to address in 2018?

This article from 2016 proposed that in the field of UX, we’d see more specialized roles emerge in the near future. That certainly has been in the case. In 2017, more companies saw the value of UX and invested in it—whether through building their own UX teams or acquiring UX firms.

One skill that I think will set designers apart will be their ability to educate non-UX and product teams about its value, and more importantly, to facilitate and coach those teams. The best companies know that UX is not the job of a single team. The experience that someone has with your product is not just what happens on the screen. The UX extends beyond the screen—it’s the customer service, emails, and social media posts, and if the experience has a physical component, it’s the packaging and in-store experience too.

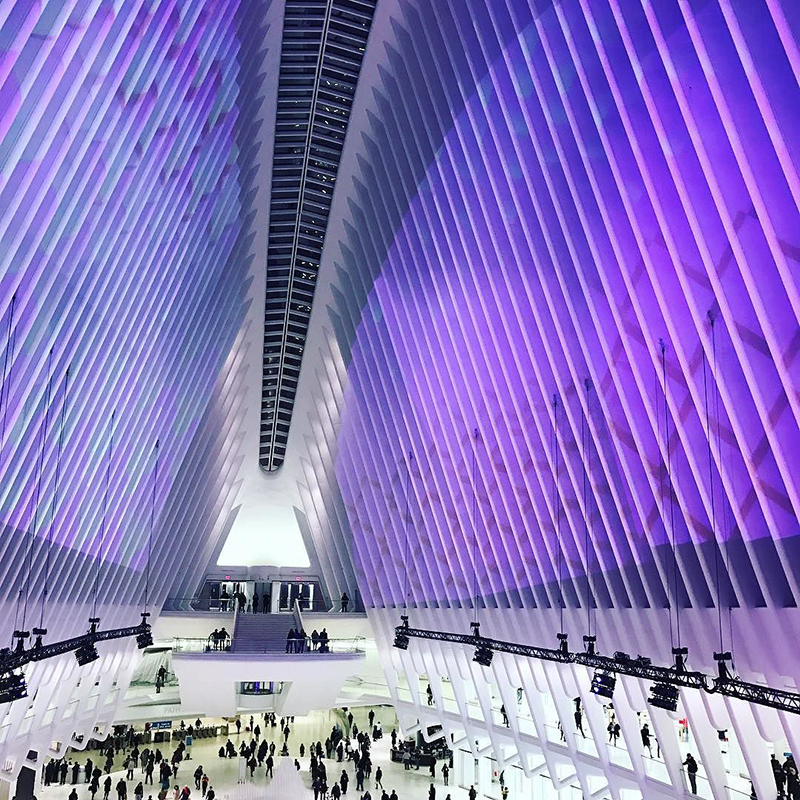

The Oculus at the World Trade Center when it was lit up for the holidays. The space is the perfect balance of chaos and peace. No matter how busy it may be during rush hour, there’s always a feeling of space if you remember to look up.

The tech industry is known to have a high barrier to entry, which can skew the demographics of the designers making interfaces we all use. If the people making the interfaces don’t necessarily represent those using them, how can designers ensure that the end product is inclusive and accessible?

I always say, “you are not the user.” In order to design an experience, you don’t need to be a user of the experience or product. I’m a runner, and if I designed a running app, of course I would be a user of the product. But, I also must recognize that I am not the user. Why? Because I’m too close to it. With anything we create, the first step in the design process must be to understand. This happens through research.

Unfortunately, many teams skip this step because they think it’s time-consuming or expensive. But research is not an expense. It’s an investment. Once you do research, you can design smarter and faster. Skipping research results in teams getting into a cycle of expensive guess-work and re-work.

With anything we create, the first step in the design process must be to understand. This happens through research.

Let’s pretend you had the funding to start any project you wanted. What would you develop?

I’ve always been interested in health and medicine. I don’t have a specific product in mind, but one problem that exists is patient compliance—meaning whether people take the medications, follow post-surgery and procedure instructions, or actually do the physical rehabilitation.

For example, it’s reported that 20 to 30 percent of medication prescriptions are never filled. What’s the impact of this? According to studies, lack of medication compliance leads to 125,000 deaths per year and at least 10 percent of hospitalizations, costing the American healthcare system between 100 and 289 billion dollars annually. From a design perspective, there’s obviously a problem to be solved. But to truly understand the problem, you have to look beyond the numbers to understand why people are not being compliant.

As everything becomes “smart,” is there anything you still enjoy doing the “old fashioned” way, and how does that affect your design work?

Due to the rapid growth of UX, we’re seeing a massive increase in methodologies and software. With all the new software, there’s a constant temptation to keep learning every new tool and method. One of the number one questions designers ask me is, “Should I learn [insert any new software name]?” My answer is always the same: “Use the tool that can get you to the desired outcome the fastest.” There’s an underlying thought that software will make you a better designer. Sometimes this is true. But first, you have to know how to think like a designer.

When I start any project, I never jump to software. I always spend time thinking through the product story through storytelling and creating storyboards. Then, guess what, I don’t use fancy software. I just sketch out storyboards in a notebook. If anyone ever looked at the storyboards, they’d be senseless. But the point of the storyboard is not that it’s an art project, it’s a conversation tool.

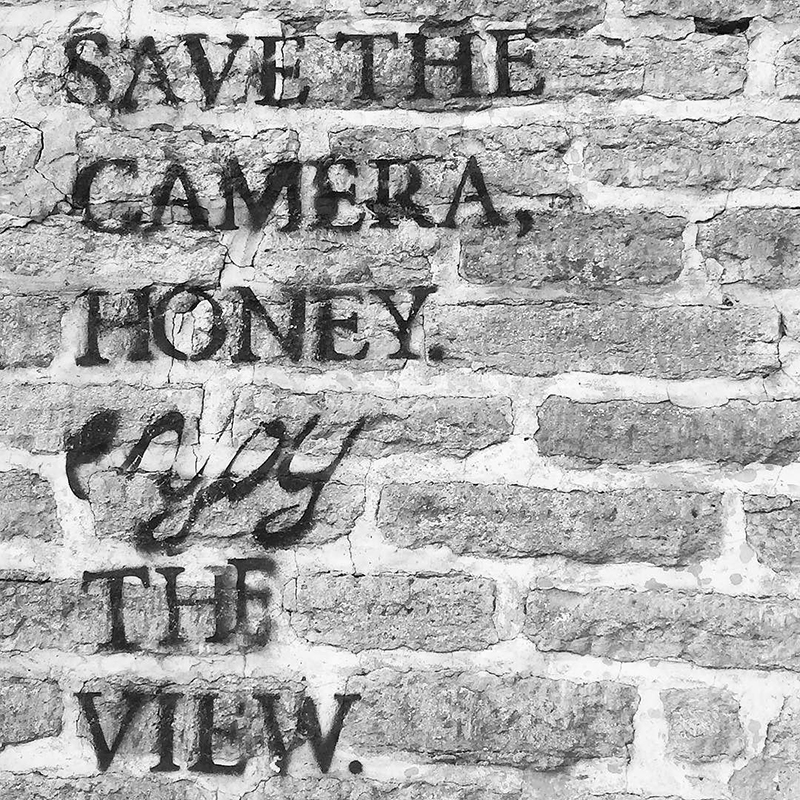

I was climbing some stairs to a cool lookout in Tallinn, Estonia and spotted this ironic reminder as droves of tourists were staring down into their phones and missing the moment in real life.

From Richard Ting: As a UX Designer / Product Designer, what criteria do you use to assess which product ideas should be designed and developed further versus being left on the cutting room floor?

Everything must be backed with research. Of course, sometimes I have a gut idea and will go with it, but I always force myself to research if that idea will actually work. It’s absolutely crucial because as designers, we’re too close to the idea. It’s easy to get stuck in the details of things and lose focus of the big picture. It’s not because we’re bad designers. But, research is what helps us maintain the balance between what we think will work and what people actually respond to. The research has surprised me many, many times.

One important point I’d like to make: research is not just looking at analytics. Numbers only tell you the what, but people tell you the why. If you truly want to understand why a design solution is working, why people are doing the things they’re doing, then you have to go beyond the numbers and focus on the narrative—and that comes from talking to users.

Next week Sarah Doody asks lead UX designer at 3M Design Health Care Business Group, Briana Como: How does a team like the 3M Health Care Group balance being a part of a huge company with the need to comply with so many details and regulations that must come with designing for health product and services?

Observed

View all

Observed

By Lilly Smith

Related Posts

Design Juice

Rachel Paese|Interviews

A quieter place: Sound designer Eddie Gandelman on composing a future that allows us to hear ourselves think

Design of Business | Business of Design

Ellen McGirt|Audio

Making Space: Jon M. Chu on Designing Your Own Path

Design Juice

Delaney Rebernik|Interviews

Runway modeler: Airport architect Sameedha Mahajan on sending ever-more people skyward

Sustainability

Delaney Rebernik|Books

Head in the boughs: ‘Designed Forests’ author Dan Handel on the interspecies influences that shape our thickety relationship with nature

Recent Posts

Mine the $3.1T gap: Workplace gender equity is a growth imperative in an era of uncertainty A new alphabet for a shared lived experience Love Letter to a Garden and 20 years of Design Matters with Debbie Millman ‘The conscience of this country’: How filmmakers are documenting resistance in the age of censorshipRelated Posts

Design Juice

Rachel Paese|Interviews

A quieter place: Sound designer Eddie Gandelman on composing a future that allows us to hear ourselves think

Design of Business | Business of Design

Ellen McGirt|Audio

Making Space: Jon M. Chu on Designing Your Own Path

Design Juice

Delaney Rebernik|Interviews

Runway modeler: Airport architect Sameedha Mahajan on sending ever-more people skyward

Sustainability

Delaney Rebernik|Books