April 6, 2018

Dancin’ to a New Tune: The Subversive, Entrepreneurial Flexi Disc

Soundgarden “She’s a Politician” flexi #21 from Reflex magazine issue 20, 1991

Aspen was a fearless, unbound multimedia magazine in a box. Founded by Phyllis Johnson, a former editor for Women’s Wear Daily and Advertising Age, the magazine was sporadically published from 1965 to 1971. Aspen had a new editor and designer for each of its ten avant-garde issues. As a result, it was continuously reinvented. In addition to many visual and written works, each box contained an audio recording on a seven-inch flexi disc vinyl record. These flexis were aurally provocative yet far from visually stunning. Printed with utilitarian white lettering, these flimsy yet unassuming sheets of black plastic contained bits of original music and readings by artists such as Yoko Ono, Marcel Duchamp, and Mario Davidovsky.

The story of the flexi is an intertwining of manufacturing, form, content, and publication. Once seen as gimmicky promotional pieces, flexis hold just a few minutes of audio. They are playable on standard turntables—and a coin may need to be placed on the disc itself to prevent slipping when played. The recording may sound slightly distorted. Central to a subculture of sound ephemera, the discs thrived through the exchange of free thought, entrepreneurship, and in some cases, subversive liberation. In short, the flexi is a vehicle for ideas.

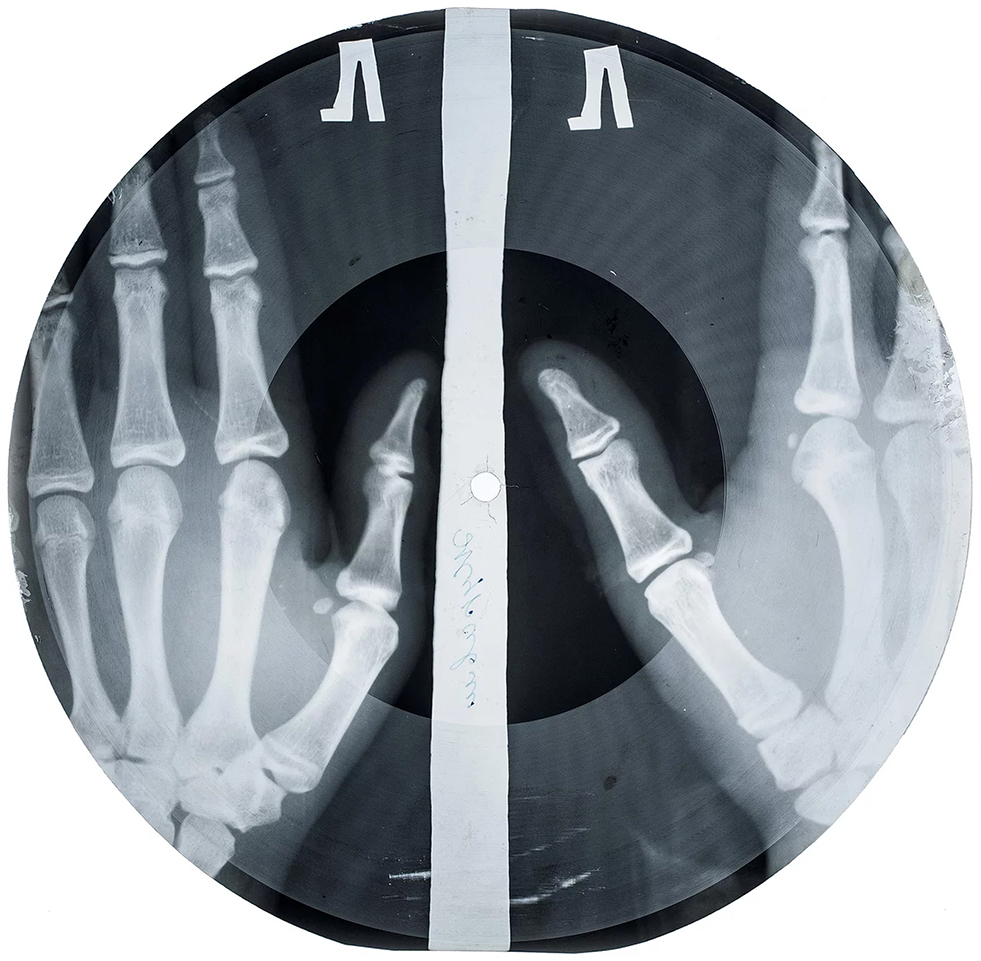

Bone record, courtesy of the X-Ray Audio Project

Handmade Bones

Early flexible records were made with discarded x-ray films and known as “bones” or “ribs.” These underground records appeared in Hungary as early as the 1930s, and through the late 1950s in the U.S.S.R. Confronted with a vinyl shortage, music fans and black market entrepreneurs transferred the forbidden music of the West to the x-ray films of anonymous bones. They were hand-cut into a circular shape, a cigarette butt may have been used to create the center hole, and then the product was secretly shared or sold. Bone records were heard in dissident kitchens alongside political discussions and samizdat (reproduction and circulation of censored literature). The radical juxtaposition of ghostly bones and vinyl grooves tells tales that are undeniably human and embodies a visceral wish for musical freedom. The sound quality of bone music was far from perfect and often the tunes were not even discernible. However, published collections of these discs, such as those in the X-Ray Audio Project, are visually breathtaking.

Brian Eno “Glint” flexi from Artforum magazine (1986)

Trademarked Manufacturing

Following an official state ban that led to the decline of bone music, makeshift technologies moved toward industry patents and mass production. Eva-Tone (U.S.) and Lyntone (U.K.) established themselves as the leading manufacturers of flexis from the 1960s through the 1980s. During this time, the discs could be found everywhere, often in connection with advertisements: inside magazines, on postcards and cereal boxes, in children’s books, and as giveaways. Eva-Tone pioneered the use of lead type to create rubber stamps, and in 1962, president and CEO Richard Evans decided to launch another innovation; he debuted the company’s first flexi, trademarked as a “soundsheet” with his own audio montage. As manufacturers and not record labels, Eva-Tone and Lyntone had revealing relationships with their products. Eva-Tone gained a reputation for having a family-friendly presence and sometimes vetted their clientele (the company turned down an offer from Playboy in 1970). On the other hand, Lyntone gained more traction in the late 1970s and 1980s with the DIY punk scene and was apparently willing to press anything and everything. For example, according to a December 1977 issue of Billboard magazine, the Sex Pistols’ management sued Lyntone for illegally pressing early song cuts. The article claimed: “the company was an innocent manufacturer and didn’t know what it was producing.”

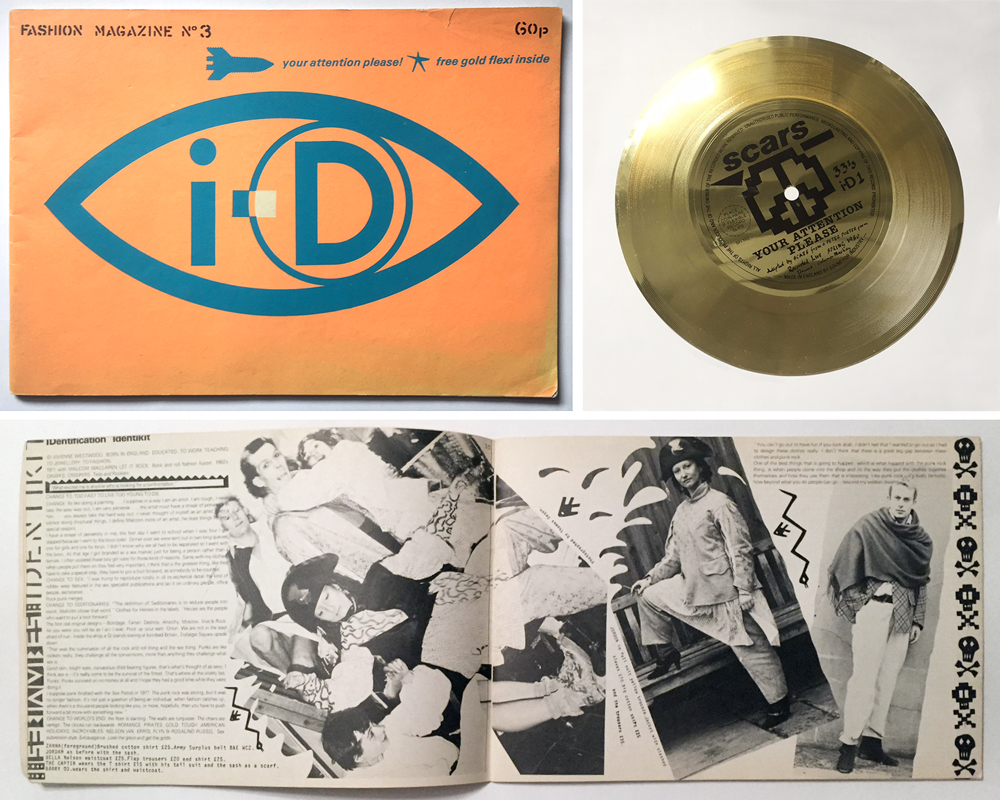

i-D magazine #3 with gold flexi (1980, courtesy of Stephen Singer)

Independent Voices

The lightweight, practical qualities of flexis were an ideal way for independent publications to entice consumers. Flexis provided a voice that reflected the unique character of their pages. Private Eye (U.K., 1961–present), a satirical magazine known for its articles and cartoons about public figures, released comedic audio recordings on covermounted flexis. Rock magazine Trouser Press (U.S., 1974–84), founded by Ira Robbins, Dave Schulps, and Karen Rose, included flexis alongside its candid, progressive criticism on music ignored by the mainstream media. Terry Jones’ i-D magazine (U.K., 1980–present) pioneered street-style fashion photography and early staple-bound issues were distributed from the back of an automobile. The sleek, gold flexi included in issue #3 contrasts with the gritty, photocopied black-and-white collage page layouts.

Flexipop! #2 (1981, courtesy of Flexi-pop! / Barry Cain) and #25 (1982, courtesy of Stephen Singer)

Considered perhaps the most quintessential (yet peculiar) of these magazines, Flexipop! (U.K., 1980 83) was founded and published by Barry Cain and Tim Lott, two former writers for the Record Mirror. The first twenty-seven issues prominently featured a Lyntone flexi mounted on the cover. Placing the translucent and sometimes brightly colored discs of original music over cover photos allowed just enough image and brazen type to show through from behind. The flexis displayed band names and song titles either boldly typeset or scrawled by hand. Flexipop! proclaimed itself an authority on pop culture extremes with its unabashedly risqué content and infantile-grotesque photo stories. Unfortunately, due to a customer complaint about the explicit content of an issue, a retailer eventually banned the magazine and production ceased a short while later.

![]()

The Sea and Cake “Flores” Joyful Noise series flexi (2013), J. Barness and V. Giles “hEar Pixels” flexi (2015)

Inspired Revival

Demand for flexis declined during the 1990s but digital media didn’t entirely kill the flexi disc star. When Eva-Tone closed in 2000, the company sold off its equipment as scrap. But in true entrepreneurial flexi spirit, Matt Jones revived the manufacturing technology nearly a decade later and thus began Pirates Press (U.S., 2010–present). Though magazines such as Decibel continue to include discs in their deluxe subscription issues, the flexi also sparked other types of experimental work. Independent record label Joyful Noise released a subscription-based series from 2012 to 2016 and each edition included an elegantly designed wooden case to house twelve flexis. Third Man Records, the independent recording label founded by artist Jack White, released a single as one thousand flexis attached to helium balloons. Thomas Dudley at Sightlab designed the single for Taushiro’s song “German Army” as two transparent, colored discs that must be carefully layered to decode the label artwork. And to personally attest to the draw of the medium, I produced a flexi with my collaborator Vince Giles to explore cut-and-paste sound collage and remix.

In the current cultural milieu of streaming audio, an emphasis is shifting toward the novelty of these discs as physical, designed objects. Flexis will wear out over time. Nonetheless, their impermanent materiality is a compelling means for expression through both form and content. Through subversive circulation or distinctive design, the flexi endures as an agent for free-thinkin’ cultural enterprise.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Jessica Barness

Recent Posts

The New Era of Design Leadership with Tony Bynum Head in the boughs: ‘Designed Forests’ author Dan Handel on the interspecies influences that shape our thickety relationship with nature A Mastercard for Pigs? How Digital Infrastructure is Transforming Farming and Fighting Poverty DB|BD Season 12 Premiere: Designing for the Unknown – The Future of Cities is Climate Adaptive with Michael Eliason