Cover of After Photography by Fred Ritchin (W.W. Norton & Company), from which this essay is excerpted

Unmasking Photo Opportunities, Cubistically

The curious reader [of the future], however, might want to place the computer cursor on the image. Another photograph appears from beneath it; it is of the same scene but from another vantage point. U.S. soldiers are pointing their guns not at any potential enemy but at about a dozen photographers who, lined up in front of them, are photographing them. In fact, the photographers are the only ones doing any shooting.

The contradictory “double image” is cubist; reality has no single truth. Perhaps these soldiers are heroes, and perhaps the U.S. government is justified in its invasion. Maybe they have to lie prone on the tarmac, anxious about an unseen enemy. The additional photograph asks the question “Is this for real?” Or is this a simulation of an invasion created for the cameras? As Washington Post editor Benjamin Bradlee described a similar situation, invoking quantum physics: “Readers — and especially television viewers — must understand the Heisenberg principle before they can understand the news. What is actually happening that is being described by the media? Is Somalia being assaulted in the predawn dark by crack U.S. troops? Or are bewildered GIs being photographed by freelance photographers who have been waiting for them for hours? The difference is often critical.”

If politicians, actors and other people in power knew that the staged event would be ex- posed by a second photograph, or by a panoramic image that similarly revealed the staging, then the subterfuge would be less worthwhile. Who would want again to spend $500,000 to air-condition an outdoor press conference of U.S., Egyptian, Israeli and Palestinian politicians at Sharm Al-Sheikh, simply so that they would not appear to be sweating, if a smart photographer would expose the ruse? She could additionally explain that in fact little progress had been made, and perhaps the half-million dollars for the temporary cooling, done for the camera, could go toward building a few schools in the Middle East.

The U.S. invasion of Haiti in 1994 as it was reported and the same scene viewed from the side. Perhaps in the future, readers of web-based publications will be able to place the cursor on the initial photo so that the contextualizing one emerges, providing a second interpretation as to what might have been going on. Bottom photograph by Alex Webb/Magnum

People will better understand that a large percentage of photographs pretending to depict something significant are showing only its simulation, often created by the photograph’s subjects themselves. The more powerful a subject is, the more he will control the simulation, while weaker and poorer people are often photographed to conform to generic but frequently less flattering imagery. A photograph that attempts to get at the complexity of individuals is considerably more rare. (A group of young Swiss photojournalists once told me that the goal of a portrait is to make the subject look nice.)

A multiperspectival strategy would help devalue spin.... Photo opportunities could be continuously shown for what they are, until media managers grow tired of putting them on. Photographs made to consciously echo other photographs, borrowing from their impact, could be paired with the previous image, exposing the vacuity of the idea. The raising of the flag at the World Trade Center towers so soon after their destruction could be shown over the image that it tried to imitate, the flag being raised at Iwo Jima, allowing the reader to consciously compare the two events.

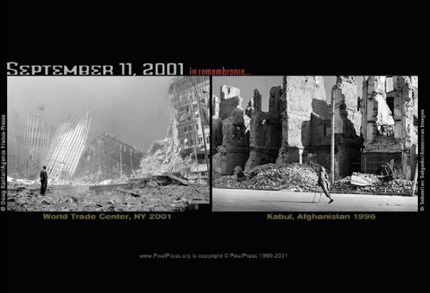

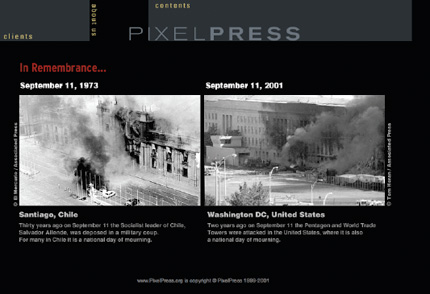

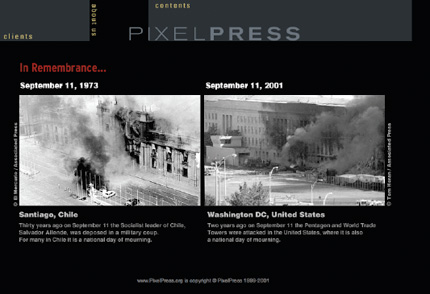

Or, as we did at PixelPress, the destruction of the Pentagon on September 11, 2001, could be presented next to a very similar photograph showing the destruction of the Chilean legislature on September 11, 1973, a result of the coup that brought down the Socialist government of Salvador Allende, another cataclysm and national tragedy. The website also showed a photograph of a devastated Kabul, an isolated figure in the foreground, next to one just like it of the destroyed World Trade Center towers before the United States began to bomb Afghanistan. Why bomb Afghanistan again when parts of it already had been devastated and looked like lower Manhattan?

PixelPress’s website showed the similarities of the September 11th attacks in both Chile and Washington, D.C. Photographs by El Mercurio/AP (left), Tom Horan/AP (right)

Photographing the Future so a Version of It Does Not Happen

The photograph in the digital environment can envision the future with enough realism to elicit responses before the depicted future occurs. Whereas analog documentary photo-graphy shows what has already happened when it is often too late to help, a proactive photography might show the future, according to expert predictions, as a way of trying to prevent it from happening. For example, creating a photograph of Glacier National Park in the year 2070 or so without glaciers, made according to reputable scientific predictions that incorporate the impact of global warming, might give the public an opportunity to seriously envision, without sensationalism, the future that may await us unless we change certain behaviors.

Photography, rather than reacting to apocalypse, can now try to help us avoid it. Robert Capa’s “If your pictures aren’t good enough, you aren’t close enough” becomes its opposite; the most distanced imagery, of events that have not yet happened, might be, in some cases, the best kind.

Of course, one would have to provide the reader with the contextualizing background, in-cluding the scientists who predicted the melting, links to their research and a label making it clear that it is not a conventional photograph but an altered one (in this case dated 2070). It is similar to the commonly used photorealistic visualization of an architect’s rendering of a future building. Certainly, this kind of “future photography” could become spurious, used for sensationalist purposes such as by unnecessarily scaring people as Hollywood has done. But it could also be quite valuable.

Another future rendering, to help the police track down missing children, has already been used for some 20 years. First devised by Nancy Burson, Richard Carling and David Kramlich, the morphed photograph, combining available photographs of other family members, is used in the creation of an image of what the growing child might look like years later. The increased realism has helped in the recovery of some of the children. There undoubtedly will be many other uses.

Enfranchising the Subject

Paradoxically, the subject of the photograph is often voiceless, unable to contest his or her depiction. Often the photographer barely knows the person, yet the image could be used to define the person or to represent a certain theme. For example, just before I came to work at the New York Times Magazine in 1978, one man had woken up on a Sunday morning to find himself on the cover for an article about the black middle class in which one of the major points was the neglect of the underclass by their better-off brethren. The photogra-pher had simply snapped his picture on the street in passing without talking to him. He then became, much to his eventual dismay, the symbol of such neglect.

PixelPress’s website showed the similarities of the September 11th attacks and the fact that Kabul, like the World Trade Center towers, had already been destroyed. Photographs by Doug Kanter/AFP (left), Sebastião Salgado/Amazonas Images (right)

If this “interactive revolution” privileges the consumer by affording more choices — like a bank ATM machine, where the “user” can choose what amount of money to withdraw, or a website with a multiplicity of consumer choices — why not also give the photographic subject a voice? Now that the photograph is immediately viewable on a camera or a computer, the subject can in many cases be asked to react to the image, or be asked to describe her own situation. Imagine a daily newspaper in which the reader can expect to hear the subject commenting on the photograph, including its merits, or articulating opinions on his situation. Walker Evans’s Alabama tenant farmers might have enjoyed the opportunity, as no doubt would a host of people depicted these past few years on the streets of Baghdad.

The subject could at times be engaged in a conversation — perhaps using a menu of questions as in Luc Courchesne’s Portrait One — so that the portraits can speak to the point. A press conference where the viewer could question an interactive photo-video of the presidential candidates to find out more about issues of greater personal interest might lead to a deeper understanding of their various stances on specific issues. It would also be a way to hold candidates accountable once in office. (According to a study by the Project for Excellence in Journalism and the Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy, during the first months of the 2008 presidential campaign, 63 percent of the campaign stories focused on political and tactical aspects of the campaign while only 15 percent dealt with the candidates’ ideas and policy proposals; a companion poll found that 77 percent of the public wanted more reporting on their positions on issues.)

The World Press Photo, based in Amsterdam, selected as its 2006 photo of the year an image by New York–based photographer Spencer Platt. The photograph shows young Lebanese driving through a partially destroyed area of Beirut after the conflict with Israel (a young woman in the car is making a cell phone video of her own).

Originally captioned, “Affluent Lebanese drive down the street to look at a destroyed neighborhood 15 August 2006 in southern Beirut, Lebanon,” the image’s contextualization was then challenged by the people in the photograph. Four of them, it turned out, lived nearby (Platt had not talked with them). While dressing stylishly, they were not affluent.

The subject could at times be engaged in a conversation — perhaps using a menu of questions as in Luc Courchesne’s Portrait One — so that the portraits can speak to the point. A press conference where the viewer could question an interactive photo-video of the presidential candidates to find out more about issues of greater personal interest might lead to a deeper understanding of their various stances on specific issues. It would also be a way to hold candidates accountable once in office. (According to a study by the Project for Excellence in Journalism and the Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy, during the first months of the 2008 presidential campaign, 63 percent of the campaign stories focused on political and tactical aspects of the campaign while only 15 percent dealt with the candidates’ ideas and policy proposals; a companion poll found that 77 percent of the public wanted more reporting on their positions on issues.)

The World Press Photo, based in Amsterdam, selected as its 2006 photo of the year an image by New York–based photographer Spencer Platt. The photograph shows young Lebanese driving through a partially destroyed area of Beirut after the conflict with Israel (a young woman in the car is making a cell phone video of her own).

Originally captioned, “Affluent Lebanese drive down the street to look at a destroyed neighborhood 15 August 2006 in southern Beirut, Lebanon,” the image’s contextualization was then challenged by the people in the photograph. Four of them, it turned out, lived nearby (Platt had not talked with them). While dressing stylishly, they were not affluent.

The BBC, among others, then interviewed and photographed the different people in the photograph and posted the results on their website — an early example of how the subjects of a photograph, in this case of a particularly emblematic one that is simultaneously mis-perceived, can talk back and will do so more in the future. Lana El Khalil, the owner of the Mini Cooper that is shown in the photograph, is uncomfortable with the picture’s selection. As she told freelance journalist Gert Van Langendonck, “It confirms what many people in the West think already, that war only happens to people who don’t look like them.”

The subjects of Spencer Platt’s 2006 photograph were individually interviewed after the image was widely distributed, selected as the World Press Photo of the Year. They challenged the initial caption,“Affluent Lebanese drive down the street to look at a des-troyed neighborhood.” Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images

The fact that photographs can be evaluated not only by the photographers, editors or readers but also by their subjects changes the power balance enormously. Now it is not only the professional outsiders depicting the insiders, but the insiders responding with their own points of view, which may amplify or contest images and captions that previously had considerable immunity from such criticism. In the case of this photograph from Beirut we might also have been able to see Bissan Maroun’s cell phone videotape as a counterpoint.

The subjects of Spencer Platt’s 2006 photograph were individually interviewed after the image was widely distributed, selected as the World Press Photo of the Year. They challenged the initial caption,“Affluent Lebanese drive down the street to look at a des-troyed neighborhood.” Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images

The fact that photographs can be evaluated not only by the photographers, editors or readers but also by their subjects changes the power balance enormously. Now it is not only the professional outsiders depicting the insiders, but the insiders responding with their own points of view, which may amplify or contest images and captions that previously had considerable immunity from such criticism. In the case of this photograph from Beirut we might also have been able to see Bissan Maroun’s cell phone videotape as a counterpoint.

Reporting as “Family Album”

Given the widening scope of the web, Berger’s ideal of “the photographer…thinking of her or himself not so much as a reporter to the rest of the world but, rather, as a recorder for those involved in the events photographed” can be concretized as a web-based family album, available to the subjects of the photographs as well as to other viewers. On the web, the photographic subjects could then recontextualize the imagery, working with or without the photographer, to provide other perspectives and to make the work their own, as was done with the website aka KURDISTAN. Photographs can then be made that are relevant to the context of those who appear in them.

Given the widening scope of the web, Berger’s ideal of “the photographer…thinking of her or himself not so much as a reporter to the rest of the world but, rather, as a recorder for those involved in the events photographed” can be concretized as a web-based family album, available to the subjects of the photographs as well as to other viewers. On the web, the photographic subjects could then recontextualize the imagery, working with or without the photographer, to provide other perspectives and to make the work their own, as was done with the website aka KURDISTAN. Photographs can then be made that are relevant to the context of those who appear in them.

Avoiding the typical approach, photographer Eric Gottesman depicted HIV-positive people in Ethiopia without showing their faces, since to do so would open them up to the scorn and rejection of their neighbors. The photographs were then transported by van to Ethiopian villages and informally exhibited to create a forum for residents to discuss their attitudes toward those with the disease and to recontextualize them. The photographer searching for the iconic image would almost certainly have concentrated on their faces and, in doing so, quite possibly revictimize them. Gottesman’s preference was for the useful image.

The outsider-insider collaboration can be a productive conversation among profoundly different points of view, each seeing some of what the other misses. Swiss-born photo-grapher Robert Frank’s now classic 1950s essay The Americans, initially detested by almost every domestic critic, brought out issues of race and class that had barely been exposed before. If done today, it might have been turned into a highly contested web-based “family album,” a referendum on what the United States has become. The subjects of the photo- graphs could have been asked to comment, adding layers of amplifications and con- tradictions to Frank’s somewhat acerbic vision. The problem would be to figure out a way to add substantive comments without so many of the meaningless comments — “nice picture,” “sexy smile” — that one finds today on many of the user-generated sites.

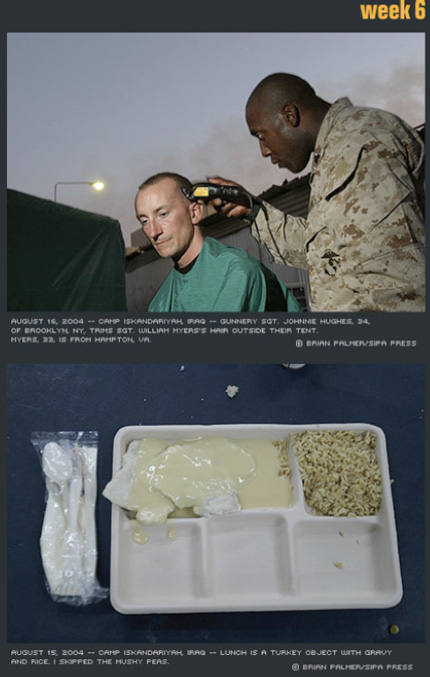

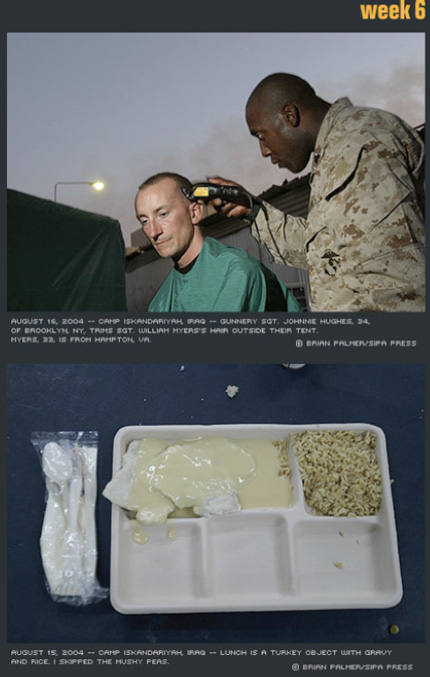

Photographer-writer Brian Palmer went to Iraq for six weeks in 2004 to follow the 24th Marine Expeditionary Unit. Published on the web at pixelpress.org as “Digital Diary: Witnessing the War,” he posted his observations weekly so that families in the United States could better understand the lives of their loved ones serving in Iraq. The chess game with a U.S. soldier and two translators, the “turkey object” that they were served so unlike the president’s ceremonial turkey that he held up at Thanksgiving, the transformation from civilian Goth to institutional Marine, all brought back the war in ways that were intimate and useful. Linked to by “www.marinemoms.com,” it was as if the photographer had become an extra set of eyes representing the families. This photography was not of strangers for strangers but of a community for those who did not make the trip.

When a young woman’s boyfriend was killed in Iraq, the photograph became essential as the last testament to his existence. “I saw the article, ‘Digital Diary Witnessing the War,’ last week and was hoping to see it again. Is there any way I can get a copy of it? My daughter’s boyfriend was with that unit and she did not get an opportunity to see the diary. Unfort-unately he was the young Marine who was mentioned in the 6th week because he was killed. We would be VERY interested in having a copy of the full six weeks if at all possible.”

The outsider-insider collaboration can be a productive conversation among profoundly different points of view, each seeing some of what the other misses. Swiss-born photo-grapher Robert Frank’s now classic 1950s essay The Americans, initially detested by almost every domestic critic, brought out issues of race and class that had barely been exposed before. If done today, it might have been turned into a highly contested web-based “family album,” a referendum on what the United States has become. The subjects of the photo- graphs could have been asked to comment, adding layers of amplifications and con- tradictions to Frank’s somewhat acerbic vision. The problem would be to figure out a way to add substantive comments without so many of the meaningless comments — “nice picture,” “sexy smile” — that one finds today on many of the user-generated sites.

Photographer-writer Brian Palmer went to Iraq for six weeks in 2004 to follow the 24th Marine Expeditionary Unit. Published on the web at pixelpress.org as “Digital Diary: Witnessing the War,” he posted his observations weekly so that families in the United States could better understand the lives of their loved ones serving in Iraq. The chess game with a U.S. soldier and two translators, the “turkey object” that they were served so unlike the president’s ceremonial turkey that he held up at Thanksgiving, the transformation from civilian Goth to institutional Marine, all brought back the war in ways that were intimate and useful. Linked to by “www.marinemoms.com,” it was as if the photographer had become an extra set of eyes representing the families. This photography was not of strangers for strangers but of a community for those who did not make the trip.

When a young woman’s boyfriend was killed in Iraq, the photograph became essential as the last testament to his existence. “I saw the article, ‘Digital Diary Witnessing the War,’ last week and was hoping to see it again. Is there any way I can get a copy of it? My daughter’s boyfriend was with that unit and she did not get an opportunity to see the diary. Unfort-unately he was the young Marine who was mentioned in the 6th week because he was killed. We would be VERY interested in having a copy of the full six weeks if at all possible.”

From week six of Brian Palmer’s 2004 “Digital Diary: Witnessing the War”

There were nearly simultaneous responses to Palmer’s postings: “I want to thank you for being with the 24th MEU. My husband is with the MEU and it is so comforting to be able to read what they are going through there. Sometimes it is hard to read about them getting hit by mortars but at least I am able to somewhat know what is going on there. I was so upset to hear that the MEU had lost a fellow Marine (Vince Sullivan). I pray for his family as well as the guys there who were close to him. Again, thank you for keeping us family members back home who are worried updated on what our loved ones are doing while away.”

Berger’s sense of recording for those photographed has found at least a partial solution. Now micropublishing is possible in an immediate, direct way. Photographing the tsunami in Banda Aceh, one can immediately transmit the photographs to websites available to those who have family and friends in the area, and to cell phones of people worldwide providing information on how they can help.

Or after the July 2005 bombing of London’s transportation system, the pedestrians who were caught in the violence created “History’s New First Draft,” as Newsweek online put it. “Through photo sharing Web sites like flickr.com and individual and group blogs, the citizen journalist played as vital a role in disseminating information this week as any brand-name media outlet,” the internet journal reported in a “Web exclusive.” (The words “photo sharing Web sites” were themselves linked to another Newsweek online article, “Photos for the Masses.”) The protagonists, while their imagery is seen world-wide, are also recording for those involved — themselves.

There were nearly simultaneous responses to Palmer’s postings: “I want to thank you for being with the 24th MEU. My husband is with the MEU and it is so comforting to be able to read what they are going through there. Sometimes it is hard to read about them getting hit by mortars but at least I am able to somewhat know what is going on there. I was so upset to hear that the MEU had lost a fellow Marine (Vince Sullivan). I pray for his family as well as the guys there who were close to him. Again, thank you for keeping us family members back home who are worried updated on what our loved ones are doing while away.”

Berger’s sense of recording for those photographed has found at least a partial solution. Now micropublishing is possible in an immediate, direct way. Photographing the tsunami in Banda Aceh, one can immediately transmit the photographs to websites available to those who have family and friends in the area, and to cell phones of people worldwide providing information on how they can help.

Or after the July 2005 bombing of London’s transportation system, the pedestrians who were caught in the violence created “History’s New First Draft,” as Newsweek online put it. “Through photo sharing Web sites like flickr.com and individual and group blogs, the citizen journalist played as vital a role in disseminating information this week as any brand-name media outlet,” the internet journal reported in a “Web exclusive.” (The words “photo sharing Web sites” were themselves linked to another Newsweek online article, “Photos for the Masses.”) The protagonists, while their imagery is seen world-wide, are also recording for those involved — themselves.

Commuter Alexander Chadwick’s cell phone photograph shows passengers in a tunnel near King’s Cross Station where a bomb exploded at 8:56 am London time. The widespread coverage by amateurs of this tragedy is credited with jump-starting the “citizen journalism” movement

For the professional photographer, providing photographs to the community being doc-umented changes the conceptual stance. One cannot depict people as exotically different and expect to be welcomed. By showing their photographs to the troops on whom their lives depend, the embedded photographers working in Iraq find that the change in audience can make it more difficult to be critically distanced, even unconsciously. Imagine if Walker Evans, for example, had shown the tenant farmers in Alabama the photo-graphs he was making of them while there, perhaps even within minutes of having taken them: would that experience have changed the succeeding images? Certainly such collaboration would allow the photographer to understand and perhaps correct certain of his own cultural stereotypes.

It might also make it exceedingly difficult for the photographer to be honest and open. Showing the work immediately constrains a certain intuition, a freedom for the photo- grapher to reflect in solitude on what is being seen and felt, and to privately discard the photographs that are less successful. One professional, Paolo Woods, explained the difference between analog and digital photography: “It’s a bit like wine: you make the wine; then you wait a while for it to become good before you drink it. But digital images, you consume immediately.”

For the professional photographer, providing photographs to the community being doc-umented changes the conceptual stance. One cannot depict people as exotically different and expect to be welcomed. By showing their photographs to the troops on whom their lives depend, the embedded photographers working in Iraq find that the change in audience can make it more difficult to be critically distanced, even unconsciously. Imagine if Walker Evans, for example, had shown the tenant farmers in Alabama the photo-graphs he was making of them while there, perhaps even within minutes of having taken them: would that experience have changed the succeeding images? Certainly such collaboration would allow the photographer to understand and perhaps correct certain of his own cultural stereotypes.

It might also make it exceedingly difficult for the photographer to be honest and open. Showing the work immediately constrains a certain intuition, a freedom for the photo- grapher to reflect in solitude on what is being seen and felt, and to privately discard the photographs that are less successful. One professional, Paolo Woods, explained the difference between analog and digital photography: “It’s a bit like wine: you make the wine; then you wait a while for it to become good before you drink it. But digital images, you consume immediately.”

Constructive Interventions

Rather than be rendered passive and guilty from the latest shocking photograph or suffering from a terminal case of compassion fatigue, the reader could be given the chance to intervene. Clicking on the image, or a piece of the image, or a predetermined corner of its frame might open up avenues where one could learn more about the situation, vol-unteer, contribute, vote, articulate an opinion or play some other kind of role. Certainly not all images lend themselves to quick, constructive responses by viewers, but providing the sense that the viewer’s concern is shared can be helpful in diminishing its role purely as spectacle. At the Georgia Institute of Technology, for example, an experiment called the Digital Family Portrait used icons on a frame containing a photograph of a family member living far away in order to update the relative’s daily condition. The idea was that the digital frame communicates the kinds of information that one would naturally be aware of on a daily basis if the relative was living next door — did a grandfather pick up his mail or take his morning walk, did he watch his favorite television program, what is the weather like over there, etc. The goal is to support peace of mind for members of the family worried about aging parents who are living on their own.

Rather than be rendered passive and guilty from the latest shocking photograph or suffering from a terminal case of compassion fatigue, the reader could be given the chance to intervene. Clicking on the image, or a piece of the image, or a predetermined corner of its frame might open up avenues where one could learn more about the situation, vol-unteer, contribute, vote, articulate an opinion or play some other kind of role. Certainly not all images lend themselves to quick, constructive responses by viewers, but providing the sense that the viewer’s concern is shared can be helpful in diminishing its role purely as spectacle. At the Georgia Institute of Technology, for example, an experiment called the Digital Family Portrait used icons on a frame containing a photograph of a family member living far away in order to update the relative’s daily condition. The idea was that the digital frame communicates the kinds of information that one would naturally be aware of on a daily basis if the relative was living next door — did a grandfather pick up his mail or take his morning walk, did he watch his favorite television program, what is the weather like over there, etc. The goal is to support peace of mind for members of the family worried about aging parents who are living on their own.

The lifeless body of an alleged collaborator is kicked and photographed in a public square in the Palestinian town of Jenin, August 13, 2006. Photo by Mohammed Ballas/AP

In other ways, the instantaneous photography allowed by camera phones is becoming a form of self-defense for civilians in all kinds of situations, even as a strategy against exhibitionism. A recent New York Daily News front page read, “Caught in a Flash: High School Girls use Cell Phone Camera to Capture Subway Perv.” If public opinion were still to have any moderating force, one way to resist an invasion by a superior military power might be to provide every civilian with a camera phone. These photographs of the in-evitable horror of war could conceivably serve as a partial brake, assuming that the public had not already been bombarded endlessly by competing and trivializing imagery.

On the other hand, “happy slapping,” an emerging phenomenon, employs the camera for its sadistic potentials, as does much of the “amateur” pornography that permeates the web. As happened at the Abu Ghraib prison, in happy slapping a victim is bullied or beaten, even raped, the cell phone capturing the incident as part of the humiliation.

In other ways, the instantaneous photography allowed by camera phones is becoming a form of self-defense for civilians in all kinds of situations, even as a strategy against exhibitionism. A recent New York Daily News front page read, “Caught in a Flash: High School Girls use Cell Phone Camera to Capture Subway Perv.” If public opinion were still to have any moderating force, one way to resist an invasion by a superior military power might be to provide every civilian with a camera phone. These photographs of the in-evitable horror of war could conceivably serve as a partial brake, assuming that the public had not already been bombarded endlessly by competing and trivializing imagery.

On the other hand, “happy slapping,” an emerging phenomenon, employs the camera for its sadistic potentials, as does much of the “amateur” pornography that permeates the web. As happened at the Abu Ghraib prison, in happy slapping a victim is bullied or beaten, even raped, the cell phone capturing the incident as part of the humiliation.

Reprinted from After Photography by Fred Ritchin. Copyright 2008 by Fred Ritchin. With permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Comments [2]

I found the thoughts on what might have happened if Walker Evans had shown the farmers the photos he had taken of them quite interesting, in light of my experiences as an amateur photographer and my travels in India. My digital camera's rear LCD screen enabled me to share the photos I took of people with them on the spot. In fact it made it a lot easier to request photos from people as there was an immediate means of sharing the result with them and thus giving them something in return for taking their image. The joy and curiosity it generated was priceless. In some instances it seemed as though some of the people had never seen a photo of themselves before and thus even though we didn't speak the same language we somehow managed to bridge the communication gap and share in something together.

So more than just a means of 'taking' photos this technology is in fact enabling us to share the photo and in a way move beyond the actual photography, to create a connection with someone even if for just a moment.

11.02.09

01:05

01.13.10

04:36