Jessica Helfand|The Self-Reliance Project

May 6, 2020

Making

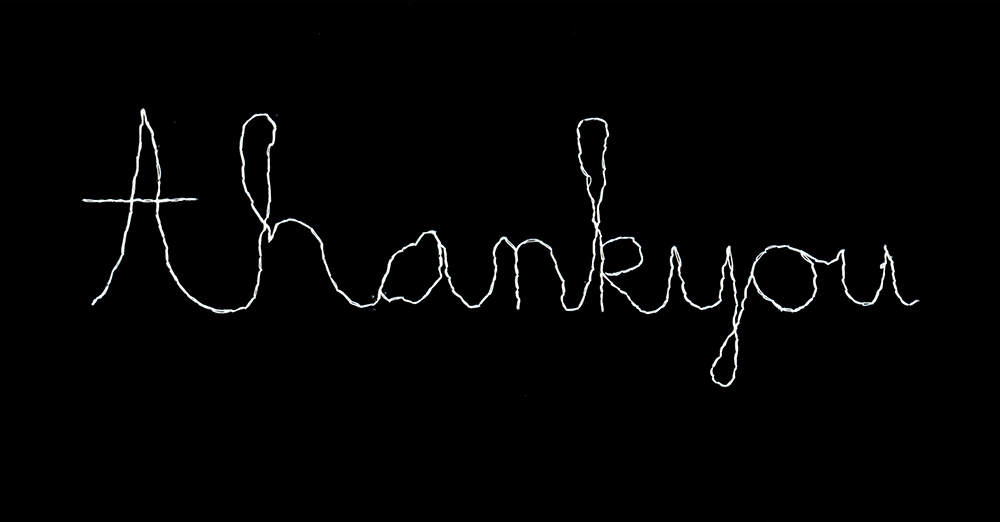

Fiona Drenttel, Thank You. Embroidery on napkin, 2010.

When I four years old and about to head to preschool, I was a basket of toddler nerves. Home, after all, was all I knew, and I was being forced to abandon ship. As it was later explained to me, all attempts at reason proved futile—my busy mind was, after all, on little kid overdrive—so my mother did the next best thing.

She changed the subject.

Her idea was to get me going on a project: in this case, planting a garden. There were seeds to select, beds to dig, and watering to do, all of which gave me, well, purpose.

Does a four-year-old need purpose? (We’ll come back to this.)

I persevered. I planted. My preschool terrors only mildly abated, I kept on keeping on.

And just like that, I became a maker.

Real makers produce against all odds. They shepherd and steward and question and push, turning things inside out and upside down, staying alert and keeping busy. There’s a magical, rabbit-out-of-a-hat quality about this: I once saw a book entirely constructed from plastic cutlery, napkins, and rubber bands, made by a student who was stuck on a transatlantic flight, simply because she couldn’t tolerate being away from her studio for so long.

And then, well, there’s my daughter.

In my earliest memory, it is winter. Eyeing a simple craft project at our local library one day, she stares intently at a pile of orange paper strips, pre-cut from recycled construction paper by our librarian. (The reverse side had a newsletter printed upon it.) The children have been asked to count them, eight apiece, and to line them up to simulate a menorah. Which they do. Except for Fiona, who turns hers over so that the typographic side is exposed. (She is two years old.)

Later, in our studio in the Berkshires, we tap our trees to make maple syrup, which we bottle and send to friends for the holidays. Shipping means boxing and boxing means protecting the bottles and protecting the bottles means blanketing them with something soft, and we decide that our something soft is shredded paper. So we acquire a shredder, and we shred, and shred, and shred some more. Soon there are huge bags of shred, and minuscule fragments of airborne, amputated words spilled out across the floor of the studio, until they are quietly rescued by Fiona, who uses packing tape to make them into collages that resemble a kind of accidental poetry. (She is eleven.)

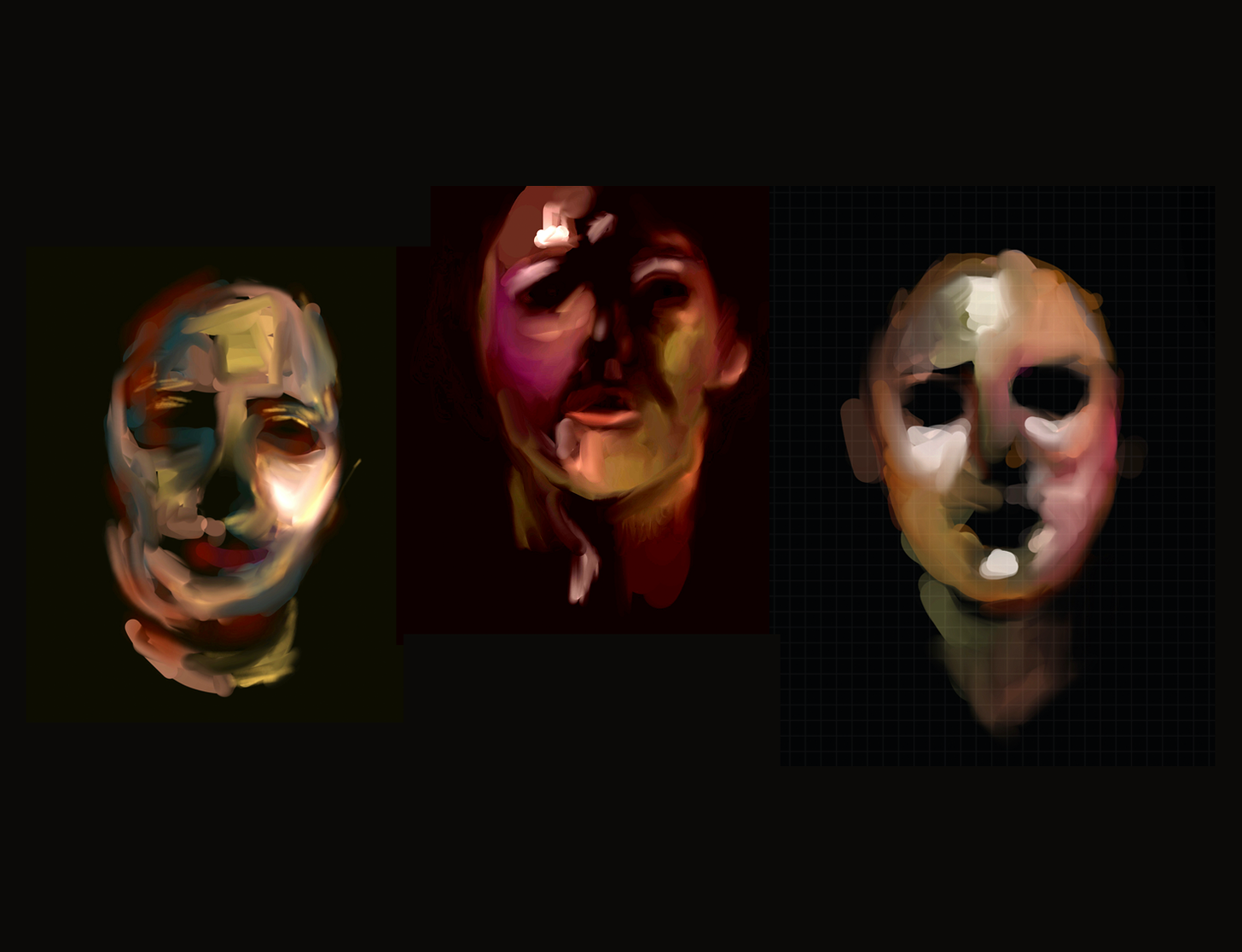

From there, she sews letterforms into napkins, weaves string onto railings, makes paper in the blender, and during a brief and rather excruciating period of vegetarianism, draws forlorn maps of the world in which all the continents are made of cheese omelettes. There are masks fashioned from envelopes, pebbles reconfigured as periodic tables, typefaces constructed from cotton swabs, and a hilarious series of airsickness bags made into hand puppets. Her mind is on maker drive, and she is unstoppable.

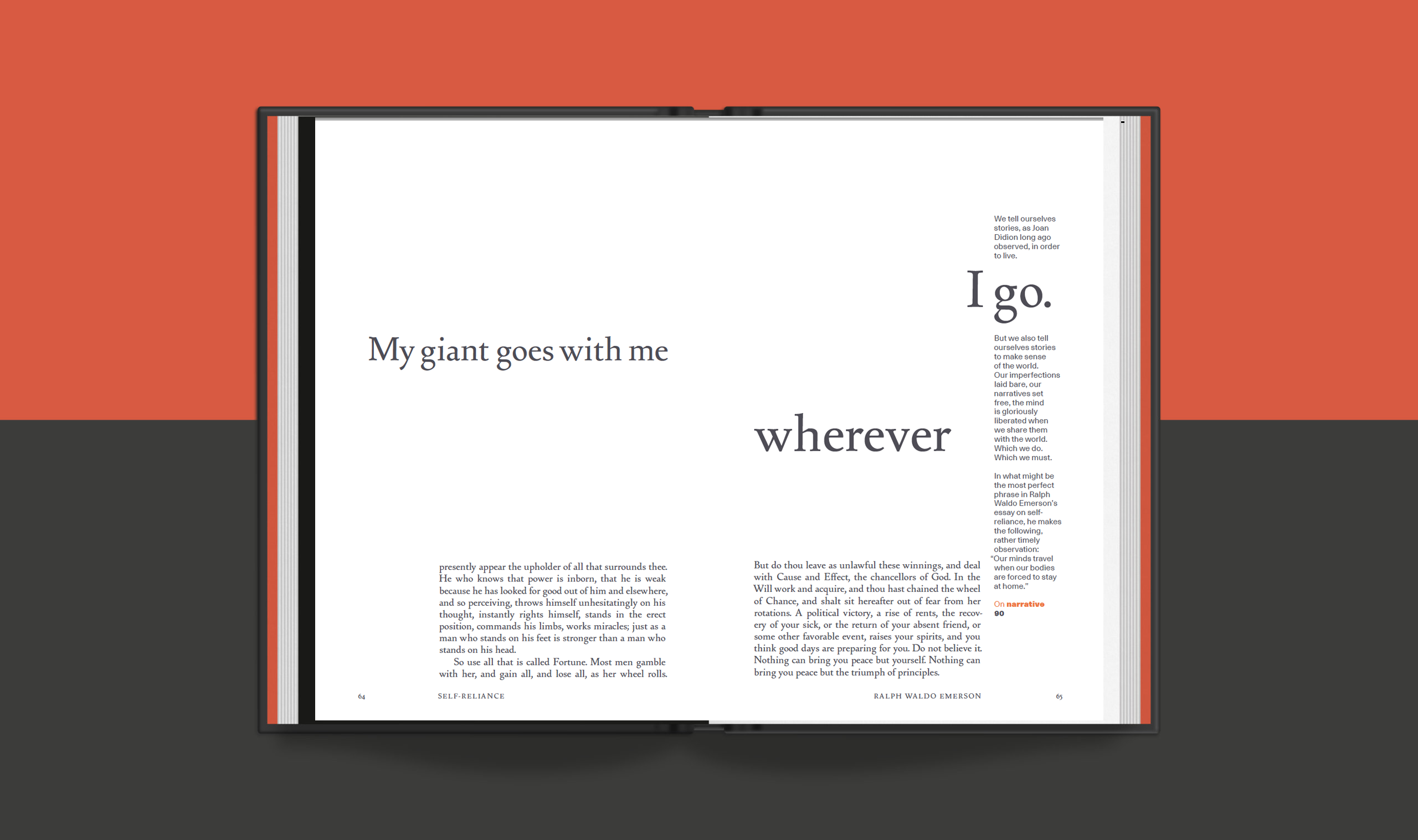

You become what you think about all day long, Emerson wrote.

Yet when it was her time to go to preschool, Fiona was was just as terrified to leave home. Did I tell her to get busy, like my mother did with me, burying her anxiety in the garden? I recall feeling helpless, remembering so vividly my own childhood fears, but also realizing that they were part of me, and that hers would be part of her. She would find a way to keep on keeping on, making things, yes, but more importantly, making her way in the world.

And she did. Next week, she’ll graduate from college: strong and beautiful, not without fear, but also, in her own inimitable way, fearless.

We don’t make things to change the subject. Those things are the subject, and the subject is us: imperfect, fragile, ever evolving, all of it work in progress. Even makers have fear. But we also have hope. And along the way, we make what we will, ever persevering, and tending our gardens as best we can.

The Self-Reliance Project is a daily essay about what it means to be a maker during a pandemic. Sign up to get it delivered to your inbox here.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Jessica Helfand

Jessica Helfand, a founding editor of Design Observer, is an award-winning graphic designer and writer and a former contributing editor and columnist for Print, Communications Arts and Eye magazines. A member of the Alliance Graphique Internationale and a recent laureate of the Art Director’s Hall of Fame, Helfand received her B.A. and her M.F.A. from Yale University where she has taught since 1994.

Jessica Helfand, a founding editor of Design Observer, is an award-winning graphic designer and writer and a former contributing editor and columnist for Print, Communications Arts and Eye magazines. A member of the Alliance Graphique Internationale and a recent laureate of the Art Director’s Hall of Fame, Helfand received her B.A. and her M.F.A. from Yale University where she has taught since 1994.