Thomas Rinaldi|Books

May 12, 2021

Origins of Design Patents

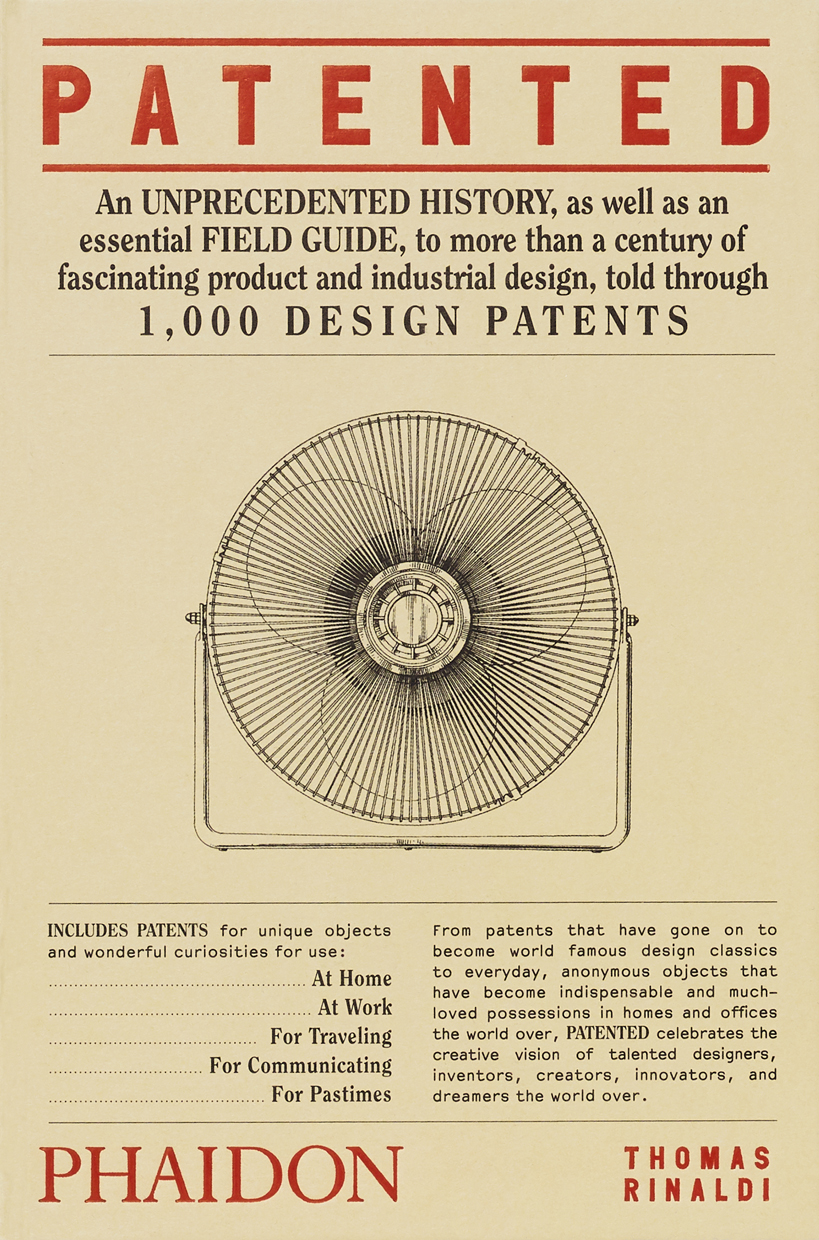

Editor’s Note: The following is an excerpt from Patented: 1,000 Design Patents by Thomas Rinaldi (Phaidon) and is reprinted here with permission from the publisher.

Although the story of design patents is closely intertwined with that of industrial design, in fact design patents predate the emergence of industrial design as an organized professional discipline by nearly a century. What’s more, design patents are issued for works whose provenance belongs to other disciplines, such as fashion or graphic design. Their legal mandate is to guarantee designers the proprietary use of their work for a set period of time. While the legislation governing their issuance and enforcement has been revised through the years, the basic function of design patents has remained basically the same since 1842.

As a modern legal concept, patents came out of the Industrial Revolution in England during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. One year after enacting its new Constitution, the U.S. government adopted patents into its own legal system with the Patent Act in 1790. Borrowing from English precedent, the idea was not simply to guarantee fair treatment for inventors: the system sought to stimulate technological development by rewarding competitive innovation while at the same time making new inventions a matter of public record so that inventors could build on each other’s work.

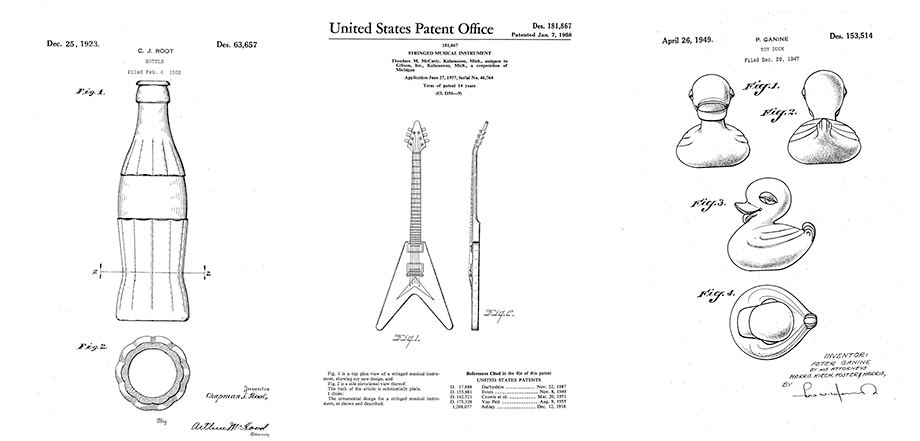

By the nineteenth century, advances in industrial processes such as casting, stamping, weaving, and cutting had given rise to mass production. This reality carried with it certain aesthetic implications. While manufacturers availed themselves of these innovations to produce more goods at lower cost, consumer expectations demanded that the manufactured origins of these goods not overly cheapen their appearance. At the same time, other technical developments enabled the application of decorative patterns that, used judiciously, could help manufacturers conceal the industrial processes employed in making their goods while adding decorative flair to lend their products consumer appeal in a competitive marketplace.

Thus by the 1830s American manufacturers saw real monetary value in design for mass-produced goods. But existing patent law in the United States, intended to protect how things worked rather than how they looked, proved ill suited to protect product design. So manufacturers (notably Jordan L. Mott, owner of a New York ironworks) began lobbying for a new type of legal protection to defend against “design piracy.” Their efforts culminated in what became known as the Design Patent Act of 1842, a federal law that, like its predecessor, took cues from England as a precedent.

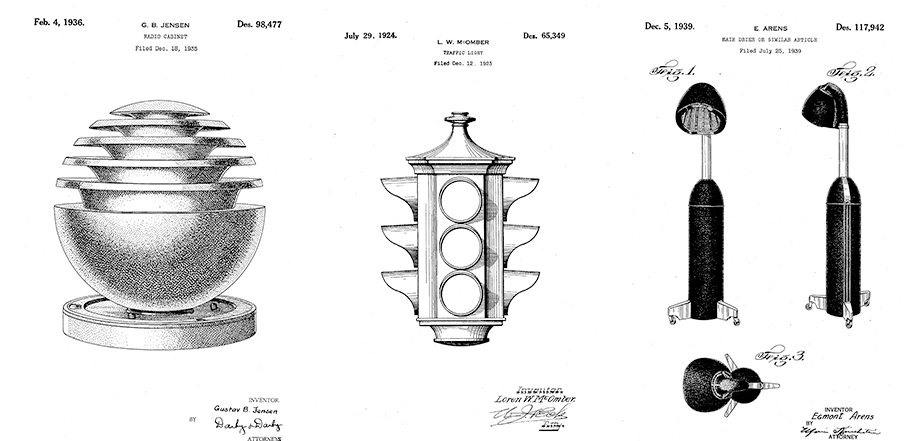

The Patent Office issued just fourteen design patents in the law’s first year. These included designs for a typeface, a candelabrum, cast iron stoves, and a bathtub, a “corpse preserver,” and a decorative pattern for an oilcloth floor covering. As initially crafted, design patents proved to be something of a blunt instrument. With the volume of mass-produced goods steadily rising, the shortcomings of the original statute forced a major re-writing of the legislation in what came to be known as the Patent Act of 1902. Rather than set forth specific lists of patentable objects as had been done previously, the Patent Office thenceforth operated on the basis of a one-size-fits-all statute to protect “any new, original, and ornamental design for an article of manufacture.”

Observed

View all

Observed

By Thomas Rinaldi

Related Posts

Sustainability

Delaney Rebernik|Books

Head in the boughs: ‘Designed Forests’ author Dan Handel on the interspecies influences that shape our thickety relationship with nature

Design Juice

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Books

Less is liberation: Christine Platt talks Afrominimalism and designing a spacious life

The Observatory

Ellen McGirt|Books

Parable of the Redesigner

Books

Jennifer White-Johnson|Books

Amplifying Accessibility and Abolishing Ableism: Designing to Embolden Black Disability Visual Culture

Recent Posts

A quieter place: Sound designer Eddie Gandelman on composing a future that allows us to hear ourselves think It’s Not Easy Bein’ Green: ‘Wicked’ spells for struggle and solidarity Making Space: Jon M. Chu on Designing Your Own Path Runway modeler: Airport architect Sameedha Mahajan on sending ever-more people skywardRelated Posts

Sustainability

Delaney Rebernik|Books

Head in the boughs: ‘Designed Forests’ author Dan Handel on the interspecies influences that shape our thickety relationship with nature

Design Juice

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Books

Less is liberation: Christine Platt talks Afrominimalism and designing a spacious life

The Observatory

Ellen McGirt|Books

Parable of the Redesigner

Books

Jennifer White-Johnson|Books