Joseph Grigely is an American visual artist and scholar. His work is primarily conceptual and engages a variety of media forms including sculpture, video, and installations. Grigely was included in two Whitney Biennials, and is also a Guggenheim Fellow. His work is currently on display at the MassMoca.

Louis Rhead (1857-1926) is perhaps one of the most unorthodox fly tiers ever — he was to fly tying what the ‘mad’ potter George Ohr was to ceramics. Born in England among a family of artists, Rhead was educated in Paris and developed a reputation as an illustrator of posters and children’s books. In 1883 he emigrated to the US, and took up trout fishing shortly thereafter. He developed his own fly and lure patterns and sold them directly to the public. His best known books include American Trout Stream Insects: A Guide To Angling Flies and other Aquatic Insects Alluring to Trout (1916) and Fisherman’s Lures and Game-Fish Food (1920). Rhead died of a heart attack in 1926 when, after a long tussle with a 30-pound snapping turtle that had been pillaging his trout ponds, he collapsed on the shore and died.

So—this post is about...tails. Sort of. Only not about ‘tails’ in any conventional sense.

It’s about Fly tails and plum tails.

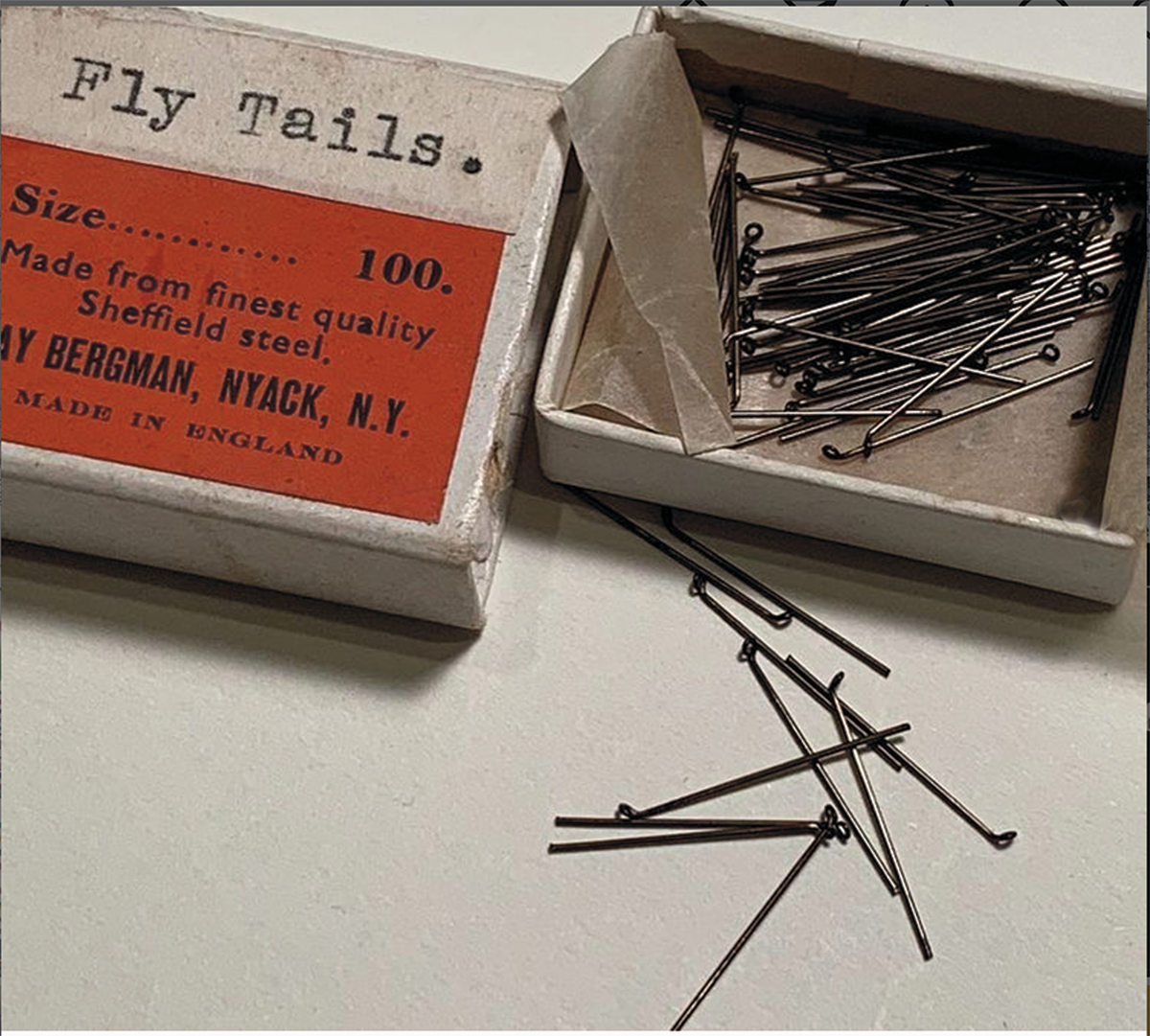

Fly tails. They consist of a hook eye and straight shank. No bend, no barb, no point. The eye is probably what you would find on a size 18 hook. These were sold by Ray Bergman, probably in the 1940s or early 1950s. Bergman was one of the premier angling authors in mid-century America. His books include Just Fishing (1932), Trout (1938), and Fresh Water Bass (1942). Bergman’s expansive knowledge was irreproachable. Capitalizing on his reputation, he established himself as a retailer of fishing goods. However, Bergman’s 1942 catalogue does not list ‘Fly Tails.’ The famous red-label box, which denoted his highest quality hooks, would suggest they were especially prized, though their purpose is not clear.

Charles Ritz, Arnold Gingrich, and John Alden Knight streamside, probably late 1950s or early 1960s. I’m not sure where but it was close to NYC as Gingrich is still dressed for the office. Here’s a favorite Labor Day quotation from Gingrich’s book The Joys of Trout in a chapter on the famous angling-author A.J. McClane: ‘For twenty-five years Al McClane had an office, but it was one where, if he showed up, he was likely to be asked, “Why the hell aren’t you out fishing?” For common mortals who have an office, when they don’t show up there, but have been out fishing instead, the questions is, of course, “Where the hell have you been?” Obviously any man who can arrange to get that question reversed is just as much smarter as all the rest of us.’ Happy Labour Day everyone.

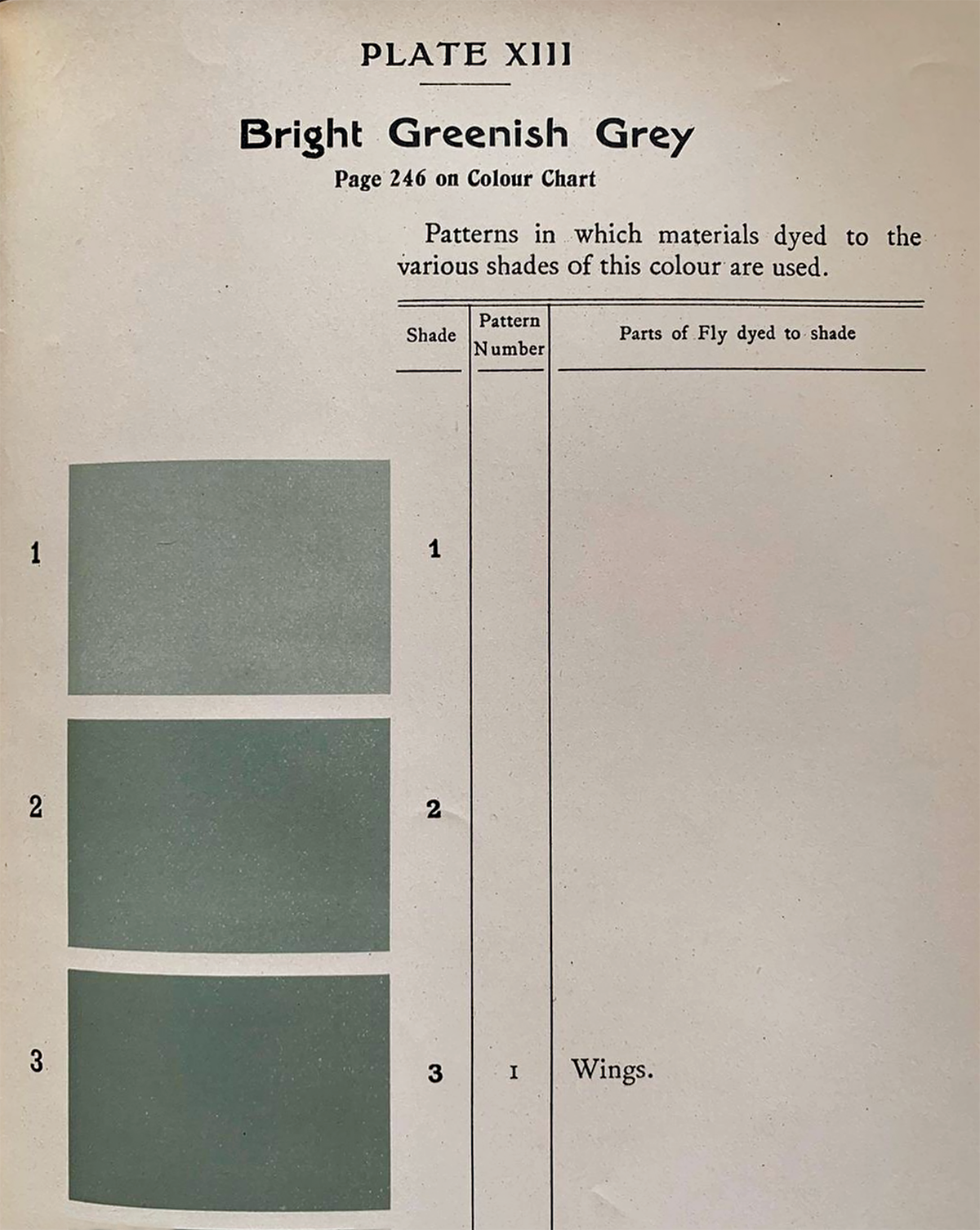

Fly design covers many parameters: similitude in relation to natural insects, size, colour, and hydrodynamic action — that is, how the fly is designed to move in the water. Frederic Halford’s Modern Development of the Dry Fly, published in London in 1910, is one of the more iconic texts related to fly design.

Six ducks, a coot, a swan, a loon, and a goose: decoys from Roger Brown’s collection, New Buffalo, Michigan. Decoys play an important role in the history of representing nature. In the process of being made (by an artisan) and then being used (by a hunter), they take nature from outside to inside, where it is reshaped and remade, and then taken outside again where decoys are employed with the task of deception—fooling birds into believing they are the real thing.

Not all decoys were made to be used; many were carved as an art form, and the auction prices reflect it: several have sold in the range of $500,000 – $800,000. Brown mostly paid between $50 – $100 for his decoys, which he found in antique shops in the 1980s. Most were made from pine and cedar. More than being quaint curiosities of a bygone time, Brown’s collection of decoys reflects an idiosyncratic way in which he collected different creative practices as a way of influencing his own. He liked stuff that was outside the norm of the artworld’s inside: wood sculptures from Africa, slipware pottery, Navajo blankets, Howard Finster’s texts and assemblages, Russel Wright dinnerware. Much of the work Brown collected was emphatically hand-made: it’s ‘slow’ art.

In a world like ours, where doing more, and doing it faster, is becoming the modus operandi, it is a relief to find meaning in doing things slow, and doing things in an understated way.

The last of the dead flowers, for now anyhow. The dead flowers idea in our house belongs to Amy Vogel, who for most of the 20-odd years I have known her has explored in her work the difficulty of beauty. The phrase actually comes from the wonderful plant magician, Paula Hayes, who, one day, was telling me a story about a blind baby who imitated, perfectly, the sound of the refrigerator and the sound of a car coming up a gravel driveway. ‘Beauty is difficult,’ Paula said to me. ‘Never forget that.’