For the first eleven years of my career I worked under the same creative director in the same design department with largely the same group of designers, editors, and marketers, most of whom had worked together for ten years before I started, making me “the new guy” up until the very end. We had our own traditions, myths, and fables and it was sharing these stories that made us more than coworkers. Our collective friendship led me to forget that business was the why of our togetherness.

Then one day, over the course of three short hours, the professional threads that bound us were snipped. It was a comprehensive reorganization. The layoffs weren’t personal, or malicious, they were a financial correction—a paragraph in a multipage business strategy. At the end of that day, instead of being laid-off, I was offered a job in another division—a promotion. Grief, relief, and survivor’s guilt mixed and soured in my stomach.

Those three hours changed me, but a persistent fear of losing my job predates that experience. It’s not a reactive anxiety, I’ve never been asked to leave a job before, and in that way it’s similar to my childhood fear of death, I’ve never died before either—at least not that I can remember. My parents were raised Catholic, and raised me with an agnostic perspective, but there was a faint scent of atheism in the air. The cold, concrete sense that I would one day no longer exist gripped me. By the age of six I regularly cried myself to sleep. Looking back I would sum it up as the fear of losing my recently acquired identity.

The idea of losing my job also equates to a loss of self—the image of myself as a designer. I fear that I’d never find another seat at the table and would be forced to change professions altogether. That fear is not neurotic, or born from imposter syndrome, it is a reasonable response to the shape of graphic design’s history and culture. The tools of the design trade have shifted hard and often enough that meeting former designers is not uncommon. So it’s not outlandish to imagine that your career might end before you’re ready to retire. But the prospect of no longer identifying as a designer poses an existential threat that cuts even deeper than financial concerns.

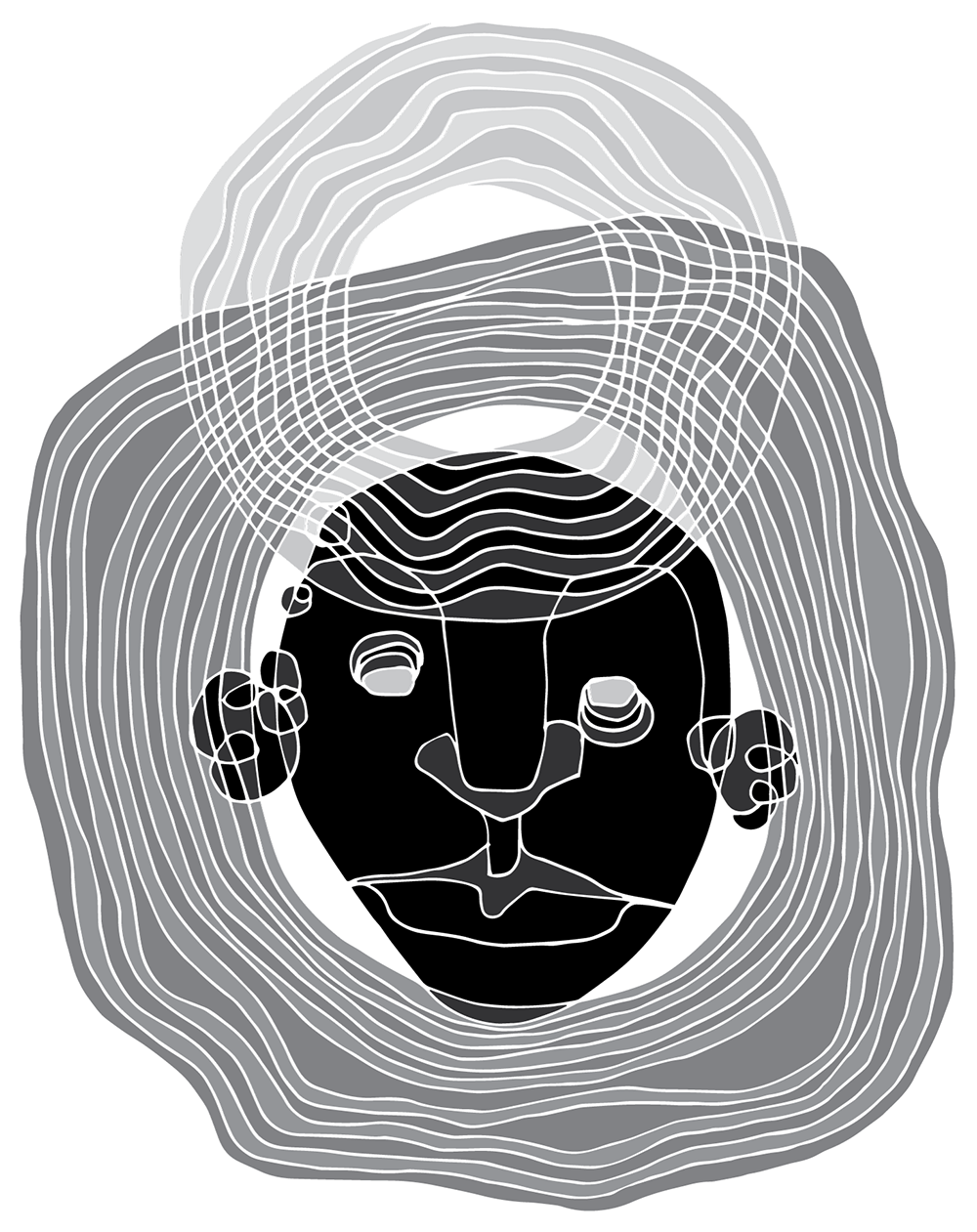

Art school begins with the realization that your talent is mundane. Magnet school magna-cum-laudes are mashed into dorms and knocked down from hometown heights by the blinding talent of their dorm mates. Becoming dislodged from the uniqueness of your creativity can be dizzying, but fear not, the faculty have a cure. Across departments professors demand that the monochromatically talented young hordes find their unique voice. We’re urged to pull ourselves into the brilliant, kaleidoscopic color of our true selves. The brand of self that we’re sold is inextricably bound to our chosen discipline. We’re told that we’re painters, illustrators, sculptors, and designers and that the thing that sets us apart from our peers is the way we practice our craft. Over the course of four years, practice calcifies into personification, and the line between ourselves and our work blurs. We become a snake eating its own tail. Our work is our identity—our identity is the reason we work. Striving for excellence in the things that we make becomes indistinguishable from striving for excellence within ourselves.

But practicing service disciplines, like graphic design, first requires permission from a client. Yes, you can make design work for yourself, but the vast majority of designers are not entrepreneurs, and at a certain point the line between self-initiated design work and conceptual art, or experimental poetry, dissolves completely. As designers, by and large, we serve clients, and as a result we are forced to ask for their permission to be ourselves. School molds us into the embodiment of our craft. If a client then denies our request to practice that craft it can feel akin to being denied breath.

When we dispatch our minds in service of our clients and their customers we’re left with holes. We empty ourselves into the work—into the ideas of the people we work for. The design field is brimming with large personalities but the work itself must be done without ego. It’s not surprising then that “empathy” has transcended buzzword status to become the cornerstone of our discipline. Empathy is undeniably important, but our obsession with our clients and their customers, born from our obsession with our craft, has caused us to forget ourselves. What design needs more of now isn’t empathy, it’s self-awareness.

“Research suggests that when we see ourselves clearly, we are more confident and more creative. We make sounder decisions, build stronger relationships, and communicate more effectively.” — Dr. Tasha Eurich

Organizational psychologist, Dr. Tasha Eurich, has done extensive research on the professional benefits of self-awareness. Her findings have shown, counterintuitively, that introspection often leads to less self-awareness and worse job satisfaction. She attributes this not to introspection being patently ineffective, but rather to it being performed incorrectly most of the time. The majority of people attempt to better understand their own emotions and behaviors through a “why” lens. Why do I feel this way? Why did I do that? Dr. Eurich notes, “research has shown that we simply do not have access to many of the unconscious thoughts, feelings, and motives we’re searching for. And because so much is trapped outside of our conscious awareness, we tend to invent answers that feel true but are often wrong.” Conversely, her studies have shown that people who exhibit a high-level of self-awareness tend to approach introspection through a “what” lens. What lead me to feel this way? What caused me to do that? Beginning with “what” primes the inquiry to be active and solution-focused.

This uncommon path to actionable introspection and heightened self-awareness should sound very familiar to designers—our daily work revolves around building the “whats” of our world. What should this book feel like? What will lead someone to understand this message? Dr. Eurich’s research suggests that these same design skills that we’ve obsessively honed to the point of dissolving into them are also the key to gaining a clearer picture of who we really are. And therein lies the rub, because becoming more aware of ourselves means understanding that we are much more than just designers.

“Not to know yourself is dangerous, to that self and to others. Elaborate are the means to hide from yourself, the disassociations, projections, deceptions, forgettings, justifications, and other tools to detour around the obstruction of unbearable reality, the labyrinths in which we hide the minotaurs who have our faces.” —Rebecca Solnit

Jean-Paul Sartre, the 20th century French philosopher, used the term “bad faith” (French: mauvaise foi) to write about the relationship between occupation and self in his 1943 book Being and Nothingness. He proposes that pressure from social forces leads us to embrace false values, to lose sight of our inborn freedom, and act inauthentically. He points to the example of the waiter in the café where he’s writing. “His movement is quick and forward, a little too precise, a little too rapid…He is playing, he is amusing himself. But what is he playing? We need not watch long before we can explain it: he is playing at being a waiter in a café.”

Sometimes I hold my head and try to fit my life into the space between my hands—it doesn’t seem like there’s enough room. When I do this it feels like I’m thumping at the skin of a truth that’s usually wrapped in storylines. It feels like a glimpse of what I feared as a child. A glimpse of my identity in its rawest, most fragile, form. In moments like this I am both more and less than a father, husband, son, friend, and designer. I would still have this head to hold even if I was stripped of all these titles. Earlier I described my childhood fear of death as the fear of “losing my recently acquired identity.” As an adult I’m still gripped by the persistent sense that I’m running out of time, but I’ve learned to flip that fear around, look through it from the other end, and understand it instead as a love for being alive. I’m beginning to look at the fear of losing my job that way too, as a symptom of the love that I feel for design.