January 21, 2015

Henri Matisse: The Lost Interview

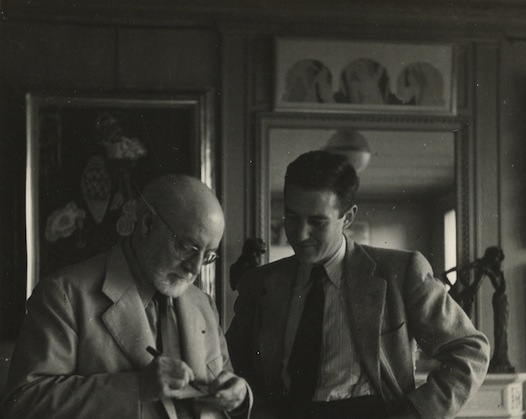

On August 5th 1946, two years after Paris was liberated from the Germans, a young American soldier named Jerome Seckler visited Henri Matisse. Seckler had a passion for modern art. He made it his mission to meet with, and interview, some of the leading French artists of the time: Matisse was on his list.

Until now this interview has never been published.

.jpg)

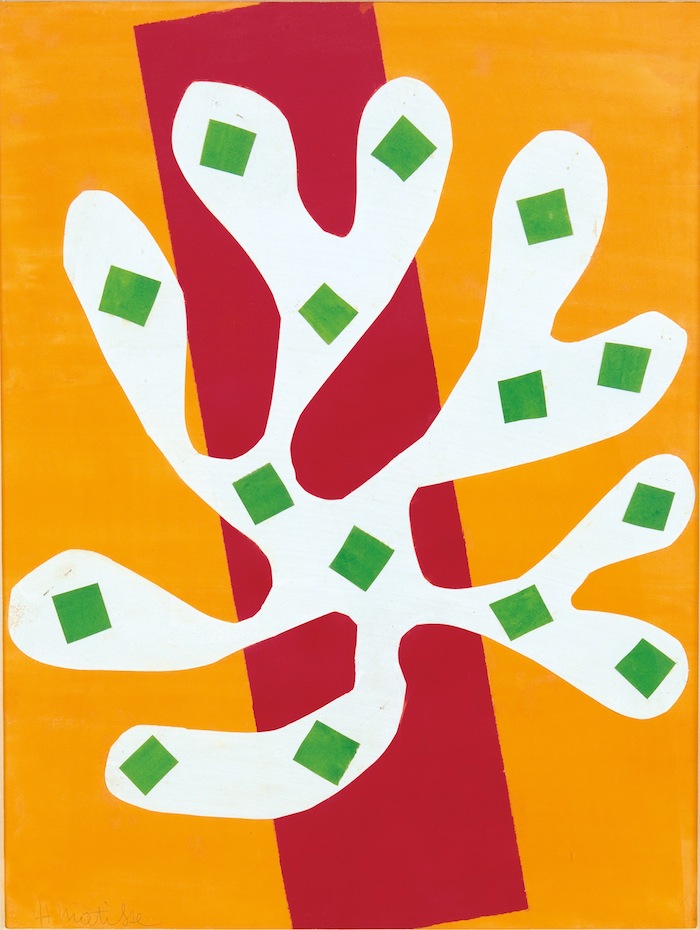

When Pablo Picasso and Francoise Gilot visited him in Vence, they found him sitting up in bed (his painting practice sharply curtailed), armed with a pair of giant scissors, holding a sheet of colored paper in one hand while a flurry of clippings—what would become known as the “cut-outs”—cascaded onto the bed covers around him. Picasso was stunned into silence. “We sat there like stones,” Gilot later recalled.

Over the next few weeks he would cover the wall, turning it into an imaginary lagoon with fish and waving seaweed, dolphins and seabirds. It would later become Oceania, The Sea and Oceania, The Sky.

++

Jerome Seckler: What is the importance of the subject in painting?

JS: I read a quote where you say you do the paintings sitting in a chair.

There is art, the project of making paintings, and what you feel. It is necessary to make a thing which is in a clear language. One day this painting will be admitted, but you can do nothing to advance that. I have always seen those who liked painting, they were the ones who didn’t have a [son?]. I once learned a man like that was following my exhibitions for twenty years and nobody knew it. People have never spoken as much of painting as now. I hope that the painter today is good, but I am not sure. In each epoque there are a certain number of artists who have counted. There is no need to have a regiment of painters. There are some artists only in each epoque. The painters believe that they exist because people speak of them. It is more simple and more difficult than that. There are several good painters in each epoque but these are very few for all those who are bad painters.

++

++

Read Part II here and Part III here.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Adam Harrison Levy

Related Posts

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Interviews

Beauty queenpin: ‘Deli Boys’ makeup head Nesrin Ismail on cosmetics as masks and mirrors

Design Juice

Rachel Paese|Interviews

A quieter place: Sound designer Eddie Gandelman on composing a future that allows us to hear ourselves think

Design of Business | Business of Design

Ellen McGirt|Audio

Making Space: Jon M. Chu on Designing Your Own Path

Design Juice

Delaney Rebernik|Interviews

Runway modeler: Airport architect Sameedha Mahajan on sending ever-more people skyward

Related Posts

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Interviews

Beauty queenpin: ‘Deli Boys’ makeup head Nesrin Ismail on cosmetics as masks and mirrors

Design Juice

Rachel Paese|Interviews

A quieter place: Sound designer Eddie Gandelman on composing a future that allows us to hear ourselves think

Design of Business | Business of Design

Ellen McGirt|Audio

Making Space: Jon M. Chu on Designing Your Own Path

Design Juice

Delaney Rebernik|Interviews