Deborah Willis, photographed, Chandra McCormick, Keith Calhoun, reported by Keith Calhoun|Aperture

August 5, 2010

Heroes of the Storm: Five Years After Katrina

Keith Calhoun and Chandra McCormick’s photographic collaboration has taken many forms, all based on love and respect for family and community. Together they have photographed dockworkers, sugarcane workers and their families, men incarcerated in prisons such as the Louisiana Penitentiary at Angola, and the expressive beauty of the local culture — including Mardi Gras “second lines,” dance, music, and foodways. Most recently the couple has focused on the effects of Hurricane Katrina on their home city, New Orleans. Both photographers were born and raised in the city’s Ninth Ward, and they have been documenting life here and in the surrounding areas for some thirty years.

Tragically, Calhoun and McCormick lost nearly their entire photographic archive and equipment when their home and studio were destroyed by Katrina when it devastated most of the Gulf Coast — and of course New Orleans in particular — on August 29, 2005.

The media coverage of the storm had begun days earlier, and the photographers decided to pack up their two sons, a niece, a brother, and a friend, and head west toward Texas, believing they would return home in a few days. Before leaving, they placed their negatives, prints, photographic equipment, and notebooks in large Rubbermaid bins that they stacked on tabletops and high shelves — a precaution that turned out to be ineffectual.

They made the nineteen-hour journey to Houston, where hundreds of families displaced by the hurricane had ended up at the George R. Brown Convention Center. There, Calhoun and McCormick were stunned by the sight of rows and rows of cots set up for the hoardes of people, all trying to make sense of this unfathomable situation. The photographers stayed for several days in the city, and eventually set up a more permanent home in the town of Spring, a suburb of Houston. It was clear they would not be going back to New Orleans anytime soon.

Sharing the one camera they had brought with them, and using a borrowed tape recorder, Calhoun and McCormick began to make a visual chronicle with interviews of people who were being housed at the convention center, as well as other displaced families living in the Houston area. There was no easy way to tell this story — but they knew they wanted to tell the version that was being ignored by the media and by the Federal Emergency Management Agency and other governmental organizations. They saw the tragedy of the loss of the familiar and the devastation of family. They also saw the communal spirit of hope that ran through the groups of people forced to live in shelters.

Calhoun and McCormick found schools for their children and settled down in Spring, though their hearts were set on moving back to New Orleans eventually. In 2006, they received a grant from the Open Society Institute (OSI) designated for projects related to the effects of Katrina. With this they were able to continue their ongoing documentation on the life of the residents of the Lower Ninth Ward — who were now relocated in Texas, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Oklahoma. Together they produced forty portraits and twenty oral histories for this project. The OSI fellowship was “a light at the end of the tunnel for us, a blessing,” says McCormick. “We were able to make a record of our experiences, create more work, and capture the stories.”

In these pages are some of the results of their work: photographs of families, church members, a solitary home unmoored from its foundation. There are also portraits of three unofficial (and unrecognized) “first responders” during Katrina: locals who stayed in the Ninth Ward after the storm and rescued more than five hundred residents there. The names of these men — Andrew Sawyer (better known as Michael Knight), Freddy Hicks, and Ernest Edwards (who goes by the nickname “All-Night Shorty”) — had come up continuously in interviews with victims of the hurricane, and McCormick and Calhoun sought them out to make their photographs.

Chandra McCormick and Keith Calhoun moved back home to New Orleans in 2007. The process of recovery is neither quick nor easy. Their photographic work goes on.

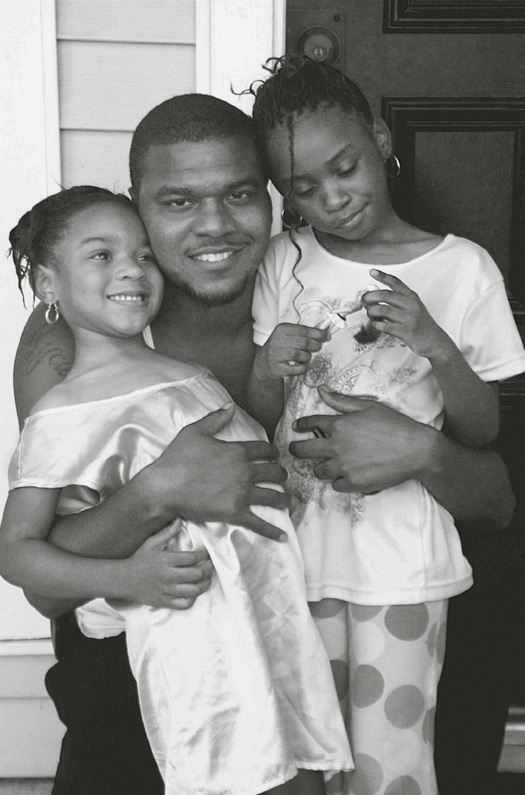

McCormick and Calhoun were deeply aware of the troubles people experienced in their new environments: families were at first accepted and later rejected in their new locations; there was no work; and there was a never-ending longing to return to their real homes. Calhoun photographed a young father and his two young daughters who were living in an apartment complex in Spring, thirty miles from downtown Houston. The family was relocated to this area; it was a very different setting from their New Orleans home, where public transportation was easily accessible. In Spring, families with no transportation had to walk nearly a mile from the apartment complex to the closest bus line. When Calhoun met them, the man was changing the oil filter on his car, in preparation for a trip back to New Orleans to assess the damages to his home. His two daughters were watching their father as he worked. Calhoun says: “I made the portrait in front of their home, with Dad holding the girls in his arms. I liked the love they displayed — despite their displacement and the hardships they were encountering.”

Before Katrina, Freddy Hicks and Michael Knight worked as salvagers and fishermen. They were watching the Weather Channel on the night of the storm, and they were planning to ride it out. But when the power went out, they decided they had to leave. Then they saw the water rolling up the street, and they knew they weren’t going anywhere.

In the days after Katrina hit, Hicks and Knight rescued between four and five hundred people. “I didn’t know they had that many people down here,” Hicks says.Â

McCormick wanted to capture the emotion Knight has about the experience in a close-up. But initially she was cautious, thinking that what happened during Katrina might be a touchy subject for him; some of the rescuers continue to be haunted by the cries of people they had to leave behind on rooftops and tree branches. “I couldn’t help but look into his eyes and wonder how he felt about the responsibilities he encountered during the storm,” she says. But Knight is extremely passionate about the welfare of the people in his community. McCormick says: “I wanted to show the strength of this five-foot-five man — who, to the people he rescued, looked as if he stood ten feet tall as he navigated his boat through waters that flooded the Lower Ninth Ward for some eight days.”

Knight is still living in the Lower Ninth Ward — his home is the only inhabited house on his block. Neither he nor Hicks left the city during or after the storm. They both tried to find work helping to rebuild and clean up their community, but no one would hire them. They were disappointed that they couldn’t make use of their skills as salvagers to help move the abandoned boats, rusting cars, and other debris that littered the area.

“All-Night Shorty” is sixty-one years old and has lived in New Orleans all his life. His home was at 2024 Deslonde Street, on the north side of the Lower Ninth Ward. He recalls Katrina hitting in the middle of the night: “At 4 A.M. the storm was in full bloom. You couldn’t see nothing.” He describes the night as “pitch white — just wind and rain, that’s all you could hear, wind and rain.”

Shorty dropped his boat into the water on North Claiborne Avenue and Tennessee Street at nine in the morning. By then, the rain had stopped and the sun had come out. On Tennessee Street the oak trees were filled with people, parents clinging to their children, screaming to be rescued. The water level was thirty-two feet.

Days before the storm, Shorty had visited his friends Michael Knight and Freddy Hicks and told them they should “gas up their boats and cars,” because “we may get a little water.” Knight and Hicks told him that they planned to stay and ride out the storm. Shorty said: “That’s fine, but you all better get ready.”

In the days after the hurricane, Shorty says, he was able to save everyone he knew who had stayed — but while rescuing those people, he saw others who were then gone when he returned with his boat. “It was a six-passenger boat, but I was taking twelve, and sometimes thirteen people at a time.” It was a harrowing time.

“I rescued a family of five — their house was floating down Jourdan Avenue. Just as we were pulling the daughter out of the house, the house went smashing into the bridge, disintegrating . . . the daughter cut her head on the side of the bridge.” Shorty is known to have carried at least two hundred people to the Claiborne Bridge, and later took boatloads from there to the St. Claude Avenue Bridge, where the Coast Guard was stationed. When Calhoun asks him why the Coast Guard wasn’t rescuing people in the area where it was most needed, he says he isn’t sure. “They should have been rescuing and transporting people. But they were parked at the St. Claude Bridge.”

A minister leading prayer on a Sunday morning. This hundred-year-old church was destroyed during Katrina and lost a number of members. It is one of the few congregations that has returned to the north side of the Lower Ninth Ward. The bridge is seen as a monument to the congregation. Calhoun wanted to capture an image of the faith that has been maintained over the past five difficult years.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Deborah Willis, photographed, Chandra McCormick, Keith Calhoun & reported by Keith Calhoun

Related Posts

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Cinema

‘The creativity just blooms’: “Sing Sing” production designer Ruta Kiskyte on making art with formerly incarcerated cast in a decommissioned prison

Politics

Ashleigh Axios|Analysis

‘The American public needs us now more than ever’: Government designers steel for regime change

Equity Observer

Ellen McGirt|Essays

Gratitude? HARD PASS

Design Juice

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Interviews

Cheryl Durst on design, diversity, and defining her own path

Recent Posts

‘The creativity just blooms’: “Sing Sing” production designer Ruta Kiskyte on making art with formerly incarcerated cast in a decommissioned prison ‘The American public needs us now more than ever’: Government designers steel for regime change Gratitude? HARD PASSL’Oreal Thompson Payton|Interviews

Cheryl Durst on design, diversity, and defining her own pathRelated Posts

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Cinema

‘The creativity just blooms’: “Sing Sing” production designer Ruta Kiskyte on making art with formerly incarcerated cast in a decommissioned prison

Politics

Ashleigh Axios|Analysis

‘The American public needs us now more than ever’: Government designers steel for regime change

Equity Observer

Ellen McGirt|Essays

Gratitude? HARD PASS

Design Juice

L’Oreal Thompson Payton|Interviews

Deborah Willis is the chair of the department of photography and imaging at the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University. A MacArthur fellow, Willis is the author, most recently, of Black Venus 2010: They Called Her Hottentot (Temple University Press, 2010).

Deborah Willis is the chair of the department of photography and imaging at the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University. A MacArthur fellow, Willis is the author, most recently, of Black Venus 2010: They Called Her Hottentot (Temple University Press, 2010).