Laura Tarrish|Hunter | Gatherer

February 23, 2015

Hunter | Gatherer

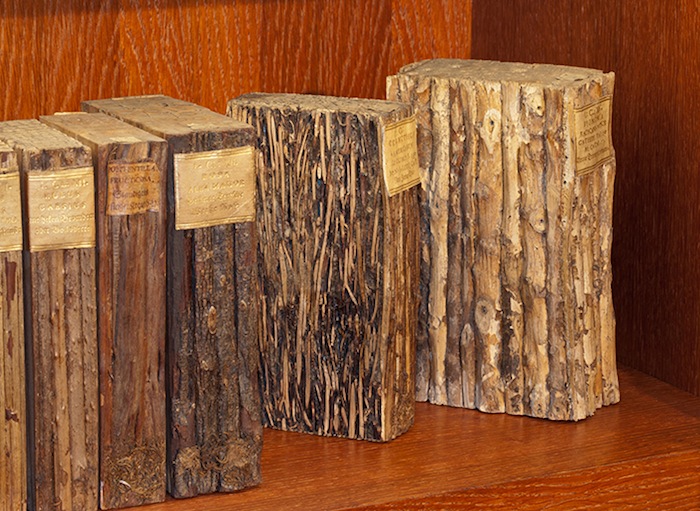

In Part II of my tree series, I turn to tree-related projects produced by scientists rather than artists. The term xylotheque is derived from xylon, the Greek word for wood, and theque, meaning repository. These book-like boxes were produced to document a range of woods and the characteristics of each source tree.

Working as a caretaker for a local menagerie and with no formal education, Carl Schildbach had an affinity for the natural sciences. Working outside the intellectual and scientific debates during the Age of Enlightenment, he created a unique fusion of book and its subject. The Schildbach Xylotheque is a 530-volume library created in the last decades of the eighteenth century. Each “book” contained the Linnaean classification number, Latin and common names, and a typical volume would include buds, branches, blossoms, a wax model of the tree’s fruit, and other related specimens. Schildbach annotated his volumes with additional layers of information, including samples of the wood in a polished state, samples of its lichen or moss, even a piece of its wood burnt alongside detailed information indicating the heat produced by its combustion and temperature readings.

Although Schildbach’s volumes were created with sliding tops, other collections were realized as hinged boxes that opened more like a book. Below, you will see examples from a 217-volume wooden library created in Nürnberg from 1805 to 1810, and currently in the collection of the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences in Alnarp.

Photos by Helena de Maré of Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences

Observed

View all

Observed

By Laura Tarrish

Related Posts

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Cinema

It’s Not Easy Bein’ Green: ‘Wicked’ spells for struggle and solidarity

Design of Business | Business of Design

Ellen McGirt|Audio

Making Space: Jon M. Chu on Designing Your Own Path

Design Juice

Delaney Rebernik|Interviews

Runway modeler: Airport architect Sameedha Mahajan on sending ever-more people skyward

Business

Ellen McGirt|Audio

The New Era of Design Leadership with Tony Bynum

Related Posts

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Cinema

It’s Not Easy Bein’ Green: ‘Wicked’ spells for struggle and solidarity

Design of Business | Business of Design

Ellen McGirt|Audio

Making Space: Jon M. Chu on Designing Your Own Path

Design Juice

Delaney Rebernik|Interviews

Runway modeler: Airport architect Sameedha Mahajan on sending ever-more people skyward

Business

Ellen McGirt|Audio

Laura Tarrish is a collage illustrator and a compulsive ephemera collector currently based in Portland, Oregon. Her editorial clients have included Apple Computer, Chronicle Books, The Washington Post, and United Airlines. As the founder of Bridgetown Papers, Laura has created custom work for individuals including Isabel Allende, Tom Brokaw and Bob & Lee Woodruff. She has been a contributor to

Laura Tarrish is a collage illustrator and a compulsive ephemera collector currently based in Portland, Oregon. Her editorial clients have included Apple Computer, Chronicle Books, The Washington Post, and United Airlines. As the founder of Bridgetown Papers, Laura has created custom work for individuals including Isabel Allende, Tom Brokaw and Bob & Lee Woodruff. She has been a contributor to