June 28, 2010

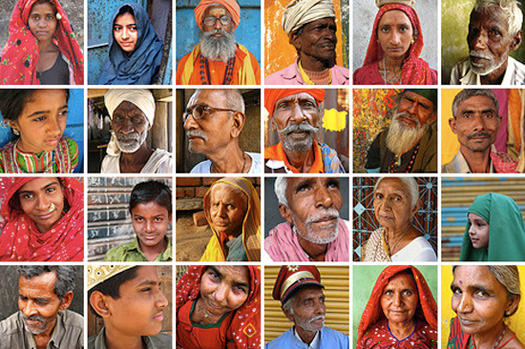

India’s Epic Head Count

More than 1 billion people of diverse cultures, languages and religions are united by India’s national borders. Between 2010 and 2011, the country’s census will not only count and categorize them by gender, religion and occupation, but also probe their access to technology, toilets and personal transport. In a monumental orchestration, aided by a newly designed census form, government departments, local councils and 2.5 million census collectors will continue the increasingly complex national effort to tally India’s inhabitants, which it has conducted every decade since the late 1800s.

The first round of national inquiry, centering on householders, has recently been completed. Early next year, a fuller head count will be sought to culminate in an ambitious plan to roll out unique national identity cards. Households have provided information on sources of water, house construction, types of cooking fuel and use of banking services that will provide statistical insights for policy makers, private enterprise, development agencies and beyond. The hotly debated question of caste did not feature in this round but looks likely to be part of the national registry questionnaire early next year after much political dispute. In an artful avoidance of the contentious query, Bollywood star Ambitabh Bachchan has already claimed that his answer to any question of caste will be “Indian.”

Indian states and districts are well aware of the importance of census numbers to ensure their future funding and so are willing to promote the effort. Local governing bodies have publicized the census through events such as street theater, school debates, folk music and cycle rallies. For the first time, some 15,000 exiled Tibetans, including the Dalai Lama, are being documented.

With challenges posed by linguistic variation and literacy levels, the census collectors play a vital role. Officially known as enumerators but unofficially as census-wallas, they record all responses on forms that are later collected, scanned and read via character recognition software. But the complexity runs deeper than that: The forms must be printed in 16 different languages, and many people have hazy recollections of their birth years while others adhere to religious calendars that run on lunar cycles. The extensive enumerator manual provides assistance by listing local dates of interest to prompt memory of known events in relation to birth years and by correlating divergent religious calendars. The manual also encourages enumerators to be gender-sensitive and explains how to record details like polygamous marriage.

The census forms were designed by Rupesh Vyas, a member of the information design faculty of Ahmedabad’s National Institute of Design. “We started the exercise with a user-study which raised contextual issues such as the possibility of low light and cramped conditions,” he noted. Such observations informed suggestions like including a backing board to stabilize the forms as enumerators took notes. Creating a form template that could support 16 different languages was an additional challenge. While Frutiger was selected for the English version, the designers had to rely on a limited font selection for the other languages, and southern scripts for Tamil, Malayalam and Telugu demanded more space. “Judicious use of real estate was required across the form, reducing redundancy and economizing information while allowing for explicit enumerator instructions,” Vyas said.

According to Vyas, the previous forms had little sense of hierarchy, alignment and consideration of proximity between instructions and relevant areas to be filled out. The constraints of intelligent character recognition (ICR) software were also factored into his designs. The paper used for forms had to exceed 80 grams per square meter for optimal ICR performance, with the total amount of paper used for the nation’s forms exceeding 12,000 metric tons. Barcodes have been employed to provide specific location details, acknowledging the comprehensive nature of both dispatch and collection in a design that has considered users’ needs alongside system-wide issues. “Prior to digital recognition technology, the census results could take six years to come out. Now we can reduce this to a mere six months, ” Vyas said.

A senior census official in Delhi was generous in his praise of Vyas’s dedication to detail. “This is such a far-reaching improvement. Visibility and clarity have been enhanced significantly but also this year’s forms are something that give census enumerators a great sense of pride.” Vyas’s faculty colleague Praveen Nahar recalls childhood memories of his own father’s involvement as a census enumerator. “The questionnaire format has come a long way since then and is certainly more user-centric. It’s a shining example,” he adds with designer-ly wit, “that forms follow function.”

Observed

View all

Observed

By Meena Kadri

Recent Posts

Mine the $3.1T gap: Workplace gender equity is a growth imperative in an era of uncertainty A new alphabet for a shared lived experience Love Letter to a Garden and 20 years of Design Matters with Debbie Millman ‘The conscience of this country’: How filmmakers are documenting resistance in the age of censorship

New Zealand–born Meena Kadri explores the intersection of communication, culture and creativity from her consultancy

New Zealand–born Meena Kadri explores the intersection of communication, culture and creativity from her consultancy