July 21, 2007

Leon Friend: One Teacher, Many Apostles

Leon Friend. Photo by Alex Rosenberg, 1969.

Abraham Lincoln High School in Brooklyn, New York, is not as famous as the Bauhaus, ULM or Cranbrook — nor is it even especially well known among most New Yorkers, despite the appearance of its old facade in Spike Lee’s movie “He Got Game.” But for over three decades between 1930 and 1969, it was a springboard for scores of artists and graphic designers. Lincoln’s art department was chaired by Leon Friend (born in Warsaw in 1902, the son of a shopkeeper in Schenectady, New York), a career art teacher with a special passion for what he called graphic design. Friend’s curriculum balanced the fine and applied arts and offered more commercial art courses than most major art schools. He introduced leading contemporary designers and inspired many of his students to become designers, art directors, illustrators, typographers and photographers. “For most of us with limited economic resources,” explained a former student, Martin Solomon (class of ’48),”the career choice was to drive a cab. Thanks to Mr. Friend, we could earn a living and be challenged by working with type and image.”

Detail, final art dept exam, circa 1939. Abraham Lincoln High School, Brooklyn.

With budgets often slashed for art education at most of today’s inner city public schools, Leon Friend’s program, which was available to low-income Depression-era (and later middle-income post-war) kids, remains a paradigm of mentoring and career development. Although art classes are often considered unnecessary in teaching the three R’s, during the Great Depression, when public funds were even more excruciatingly tight, the Lincoln curriculum encouraged creativity and critical thinking. Mr. Friend, as his students always addressed him, encouraged individual vision and collaborative activity while giving special emphasis to community service.

He accomplished in a high school setting what many colleges and universities fail to do even today: Place the applied arts in both an historical and practical context. From the freshman year his students were taught typography, layout and airbrush techniques while other schools were teaching crafts. The title of his class was “Graphic Design” (long before it was common), but the term was defined broadly. His students drew and painted, designed posters, and composed magazine and book pages. For Friend, graphic design was an inclusive and expressive activity. “We were taught honesty (in design and application), clarity (of thought and presentation), and fidelity (of concept and rendition),” wrote a former student, Edwin Orans, in a 25th Anniversary testimonial booklet.

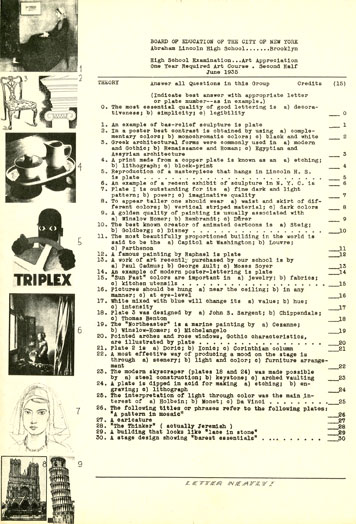

Final art dept exam, circa 1939. Abraham Lincoln High School, Brooklyn.

Friend’s curriculum was more than a departure from the standard, cookie-cutter Board of Education pedagogy: it challenged to the common assertion that art education was merely ethereal. His history classes broadened the knowledge of those who took them; his studio classes forced students to solve professional problems; and his guest lecture classes (including Laszlo Moholy Nagy, Lucian Bernhard, Josef Binder, Lynd Ward, Chaim Gross and Moses Soyer) offered an introduction to the masters of commercial and fine art. Friend’s mid-term and final exams (shown here) required that each student be versed in how the intersection of the histories of fine and applied art defined culture.

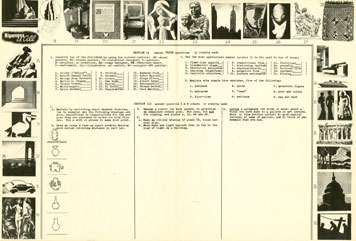

Final art dept exam, circa 1939. Abraham Lincoln High School, Brooklyn.

What other high school’s test paper included questions about perspective using E. McKnight Kauffer or A.M. Cassandre posters as visual examples? “The tests show to what extent we, as high school students, were required to comprehend the history of all art and its relationship to industrial, architectural and graphic design,” recalled another former alumnus, Gene Federico (class of ’36), who added, “Friend inspired me to become a advertising designer.”

Friend was dedicated and passionate. “He was a charismatic father figure who gave me an appreciation of typography and design and equated success in these areas with achieving nirvana,” stated Seymour Chwast (class of ’48), who saw Friend as a mentor. Needless to say, Friend was not just a catalytic presence, but a teacher who awakened joy in creative expression and knowledge. “Coincident with the discipline of learning and the practicing of what was learned was the daily contact of over a four-year period with Leon Friend, the man,” recalled Alex Steinwiess (class of ’34), the first designer of record albums who celebrated his 90th birthday this year. “This in itself was a source of inspiration and psychological strength that went far in developing in the students the rudiments of a lifestyle.”

Friend wanted his students to have every opportunity to succeed in the real world, and so he founded a quasi-professional extra curricular club called the “Art Squad,” which for its members was more important than any varsity football, basketball or baseball team. Participation in this daily (seven day a week) program was limited to thirty students per year representing all the grades. Located in Lincoln’s Room 353, Friend gave the Art Squad autonomy under the tutelage of an elected student leader who served for an eighteen-month term. Membership was by invitation and sponsorship of another student, and required a portfolio review by the membership committee. Members worked for a common cause and developed personal strengths.

New York City was once a fairly large client for posters and Friend encouraged students to enter work into city-wide public service poster competitions, as well as others for the World’s Fair, The American Cancer Society, Rapid Transit System and the Department of Sanitation (which offered monetary awards). Yet another successful alumni, Sheila de Brettville (class of ’59), chair of the graduate graphic design program at Yale University, recalls that she won a poster competition designed to encourage people to get regular medical attention. Experiences such as her’s gave students confidence and separated the wheat from the chaff in a practical manner. The real world was Friend’s laboratory.

The wide range of images available to students through his classes and his personal library included Kathe Kollwitz’ prints of war’s destruction, Cassandre’s posters of the delight of drinking Dubonnet and Savignac’s utopian thrill of locomotives. They were presented without differences as if each were equal, making it possible for each student to choose whatever and whichever subject matters were specifically of interest. Friend’s method was so successful that, according to Alex Steinweiss, “many who weren’t fortunate enough to win scholarships [to art school], went directly into the art job market upon the basis of their high school training and carved out important careers as art directors, designers and photographers.”

Among those who benefited from Friend’s classes were a who’s who of diverse talent: William Taubin (art director of the “You Don’t Have to Be Jewish” Levy’s Rye Bread campaign), Irving Penn (the photographer who began as a graphic designer), Jay Meisel (photographer) and Richard Wilde (chair of graphic design and advertising at the School of Visual Arts), among others.

Although Friend, who was not a designer himself, was inspired by the Bauhaus, he never imposed any specific doctrine on his students — other than do good work. He was, in fact, so reticent about passing on constricting dogma that he rarely referred to his own book, Graphic Design (co-authored with Joseph Hefter in 1936), which was used as a textbook in other schools. Although the book’s content is today dated, and some of the chapters were somewhat parochial even at the time of publication, Friend was one of the first American educators to introduce progressive European design ideas.

Because Friend entered the teaching profession at a time when graphic design was a potential means to escape economic hardship of the Depression, he was by necessity an exponent of practical pedagogy or what one alumnus called “the achievement method.” By allowing his students a chance to develop at their own pace and discover their own strengths and weaknesses, Friend made an indelible contribution to many lives.

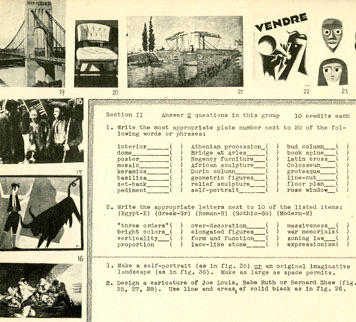

Final art dept exam, circa 1939. Abraham Lincoln High School, Brooklyn.

Detail, final art dept exam, circa 1939. Abraham Lincoln High School, Brooklyn.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Steven Heller

Related Posts

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

The Observatory

Ellen McGirt|Books

Parable of the Redesigner

Arts + Culture

Jessica Helfand|Essays

Véronique Vienne : A Remembrance

Recent Posts

Mine the $3.1T gap: Workplace gender equity is a growth imperative in an era of uncertainty A new alphabet for a shared lived experience Love Letter to a Garden and 20 years of Design Matters with Debbie Millman ‘The conscience of this country’: How filmmakers are documenting resistance in the age of censorshipRelated Posts

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

The Observatory

Ellen McGirt|Books

Parable of the Redesigner

Arts + Culture

Jessica Helfand|Essays

Steven Heller is the co-chair (with Lita Talarico) of the School of Visual Arts MFA Design / Designer as Author + Entrepreneur program and the SVA Masters Workshop in Rome. He writes the Visuals column for the New York Times Book Review,

Steven Heller is the co-chair (with Lita Talarico) of the School of Visual Arts MFA Design / Designer as Author + Entrepreneur program and the SVA Masters Workshop in Rome. He writes the Visuals column for the New York Times Book Review,