I was struck recently by a single photograph. It was an image of what appeared to be a 1950s Mad-Men era young woman with flamboyant cat eye sunglasses, leaning forward and spread-legged on a striped lawn chair. She held a martini in one hand and stared at the camera with a defiant “What-the-hell-are-you-looking-at?” pose. The setting was the side-yard of a 1950s-era, nondescript white house. This woman was every adolescent boys next-door neighbor fantasy. She was Miss Landers gone bad—perhaps the only one who could lure Ward Cleaver off the straight and narrow.

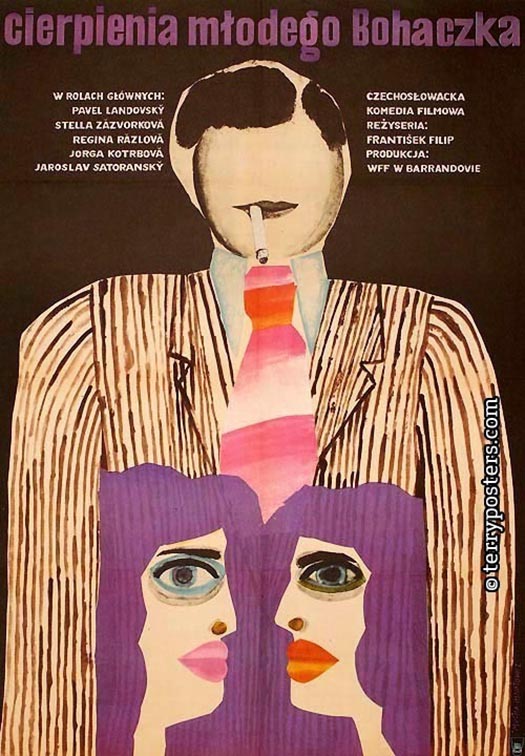

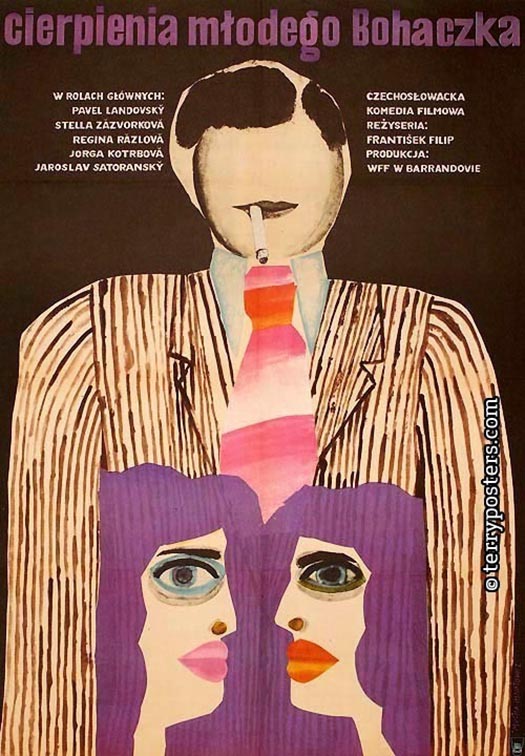

Untitled #2 (From the series Boat Girl), 2005

Untitled #2 (From the series Boat Girl), 2005

As a collector of vintage snapshot photography, I wondered momentarily if I was looking at an old Ektachrome image of the sassiest chick in town. The overwrought green tonalities were right, the image was slightly out of focus—all of this pointed to the best a point-and-shoot camera of that day could deliver. If this image happened to be a genuine vintage Ektachrome print—it would be like owning a mint condition Mickey Mantle rookie card.

But my brain and eyes overruled my libido and said it wasn’t so, so I set out to learn more about the person who created the image. The photograph,

Boat Girl Series #2, is by photographer

Marianna Rothen. I sought her out for an interview.

++

JF: Your image, Boat Girl Series #2 was how I found you. Tell me about this series—especially this particular image. Set the stage for me.

MR: Boat Girl was an interesting shoot because I was actually planning on doing self-portraits that day. It was also the very first real shoot I did upstate, the one that inspired most of my work that followed. When I arrived at the location of my friend’s house, I met Morgane, a young woman who was at the beginning of what would be a stellar modeling career. She was more fabulous then anyone I’d ever shot at the time, and I asked if she would be interested to take my place for the photos. She agreed and we spent the afternoon as strangers setting up scenarios and then I’d shoot them. … she [captured] the mood perfectly. What struck me with these images was her power in the midst of her very feminine look … unapologetic and giving me a dose of her French attitude. This has become a core thread in my work ever since.

Untitled #3 (From the series Boat Girl), 2005

JF: You were born in Canada, and started modeling at fifteen, traveling the world for your job. Obviously you were the subject of the photographer’s eye for many years—how did that early experience affect you? Did modeling professionally plant the seed for what you are doing now behind the lens?

MR: When I started, I was a quiet, mousy girl coming from a sheltered upbringing. I spent my childhood watching big American films like Sound of Music, White Christmas, and My Fair Lady. My experience [modeling] turned everything upside down. I grew tremendously. It was wonderful and difficult at times, having to stick up for myself in a tough business. I also became interested in photography around the same time—it was my “off-duty” companion, wandering the streets taking pictures. Modeling for fashion also gave me great insight into how photographers work. Often times while modeling on shoots I would imagine how I would have taken the pictures differently. Photography gave me my creative outlet and I could create my own world within that.

JF: I am reminded of another model-turned-photographer Bunny Yeager (1929–2014), who shot cheesecake photos in the 1950s, including many of Bettie Page. Female models were completely comfortable working with her—and as a model herself she knew what she wanted as a photographer. The likes of Diane Arbus and Cindy Sherman have said Yeager was an influence on their work. She liked to pose her models, and never liked to work with women who would not take direction. Have you ever felt a kinship to Bunny in the way you work as model turned photographer?MR: I am not very familiar with Bunny Yeager. There is one photo I always liked with her holding a camera and Betty Page in leopard print, but I never really researched her (but will now!). It’s so true how models feel at ease working with a female photographer who also has been a model. There is a kinship there, respect and trust.

JF: You did a series called Alien Camp, which I find fascinating. In these photographs, we see a confusion of sorts between truth and fiction, which in many ways appears to be the groundwork for all of your work. Could you elaborate on that?

MR: Alien Camp is about the in-between world of illusion, the hyper-realness in manmade structures next to idyllic natural landscapes. I shot everything with Polaroid film using dirty filtration to remove detail and amplify the effect. The end result was an image that was indistinguishable from being of a real or fake environment—a set for a film or something that exists in nature by chance. Juxtaposed together they create this uncertainty of truth or fiction. I am very interested in this idea for all of my work, to have a believability within something that is fabricated.

Untitled #1 (from the series Alien Camp), 2007

Untitled #2 (from the series Alien Camp), 2007

Untitled #2 (from the series Alien Camp), 2007

JF: There is this strong vintage quality to your photographs—your series Domesticated Woman caught my eye—but at the same time they have this quirky, post-modernist twist that links directly to feminist issues. I think this occurs in more than one series—Gentle Creatures would be another.

MR: As I mentioned, I like my images to have a humanness to them, finding a special moment in an ordinary and simple set-up. A lot of the photographs are re-creations of impressions from my childhood and teenage years, things that have left a profound impact in my imagination. Observing the domestic environment my parents created: my mother a religious stay at home mom and my father a Swiss man who had a big appreciation for American cinema of the 1950s and ’60s. My early idea of beauty came from the Polish women in my family who were always dressed up to the nines, in heavy make-up and giant curled hair. My work does reflect my move out of this and to a place of freedom from conventional living. I am interested always in a woman’s place in society, and ideas about fame and public expectations.

JF: Would you elaborate on your new book, Snow and Rose & other tales?

MR:

Snow and Rose & other tales is composed of my work covering a ten-year period. It is many little series edited into chapters and the idea was to lay it out like a film, telling a story that starts in domestic claustrophobia and ends with independence. I made the work without thinking of it being in book form and I was very surprised by its coherence, its almost in chronological order. It’s a very personal project. I was very fortunate to be approached by Roger Eberhard, of b.frank books, who had a strong understanding of my work and could visualize it in book form. It was a wonderful collaboration.

Untitled #3 (From the series Snow and Rose), 2011

Untitled #3 (From the series Snow and Rose), 2011

Untitled #3 (From the series Snow and Rose), 2011

Untitled #3 (From the series Snow and Rose), 2011

The photographs of Marianna Rothen can be seen July 3–22, 2015 at Lazypoint Variety, 208 Main Street, in Amagansett, New York. The opening reception will take place on Friday, July 3 from 6–8 pm.

++

Untitled #7 (from the series E.k.t.i.n.), 2010

Untitled #8 (from the series E.k.t.i.n.), 2010

Untitled #9 (from the series E.k.t.i.n.), 2010

Untitled #6 (From the series Boat Girl), 2005

Untitled #2 (From the series Hollie), 2012

Untitled #9 (From the series Women of Canterbury), 2011

Untitled #2 (From the series Boat Girl), 2005

Untitled #2 (From the series Boat Girl), 2005

Untitled #2 (from the series Alien Camp), 2007

Untitled #2 (from the series Alien Camp), 2007 Untitled #3 (From the series Snow and Rose), 2011

Untitled #3 (From the series Snow and Rose), 2011

.jpg)

.jpg)

John Foster and his wife, Teenuh, have been longtime collectors of self-taught art and vernacular photography. Their collection of anonymous, found snapshots has toured the country for five years and has been featured in Harper’s, Newsweek Online and others.

John Foster and his wife, Teenuh, have been longtime collectors of self-taught art and vernacular photography. Their collection of anonymous, found snapshots has toured the country for five years and has been featured in Harper’s, Newsweek Online and others.