Michael Bierut|Essays, Vignelli

May 27, 2014

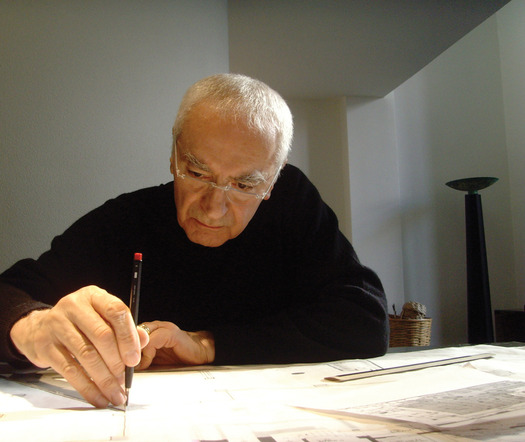

Massimo Vignelli, 1931-2014

I learned how to design at design school. But I learned how to be a designer from Massimo Vignelli.

In June 1980, I graduated from the University of Cincinnati with a bachelor’s degree in graphic design, and moved to New York City to take a job at Vignelli Associates. I can barely picture the person I was 34 years ago. I was from a middle class suburb on the wrong side of Cleveland, Parma, Ohio, the newly-hired, lowest-ranked employee at Vignelli Associates.

The tasks I would be doing at my new job would be barely comprehensible to young graphic designers today, menial operations involving rubber cement thinner, X-acto knives and Photostat developer. I was a schlub, a peon, a punk. I knew nothing. Massimo and his wife Lella were to discover very quickly that Parma, Ohio, and Parma, Italy, had very little in common.

Today there is an entire building in Rochester, New York, dedicated to preserving the Vignelli legacy. But in those days, it seemed to me that the whole city of New York was a permanent Vignelli exhibition. To get to the office, I rode in a subway with Vignelli-designed signage, shared the sidewalk with people holding Vignelli-designed Bloomingdale’s shopping bags, walked by St. Peter’s Church with its Vignelli-designed pipe organ visible through the window. At Vignelli Associates, at 23 years old, I felt I was at the center of the universe.

I was already at my desk on my first day of work when Massimo arrived. As always, he filled the room with his oversized personality. Elegant, loquacious, gesticulating, brimming with enthusiasm. Massimo was like Zeus, impossibly wise, impossibly old. (He was, in fact, 49.) My education was about to begin.

At Vignelli Associates, I was immersed in a world of unbelievable glamour. If you were a designer – even the lowest of the low, like me – Massimo treated you with a huge amount of respect. Everyone passed through that office. I met the best designers in the world there: Paul Rand, Leo Leonni, Joseph Muller-Brockman, Alan Fletcher. And not just designers. I remember one time Massimo was working on a book project with an editor from Doubleday, and he decided to give her a tour of the office. He brought her to my desk and introduced me. It was Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. “Mrs. Onassis, this is one of our young designers, Michael Bierut,” said Massimo. “It’s an honor to meet you,” said the former First Lady. I think I just said, “Guh, guh, guh.”

From Massimo, I Iearned that designing a book wasn’t about coming up with a clever place for the page numbers. He taught me about typography, about scale, about pacing, about refinement. I learned to think of graphic design as a way to create an experience, an experience that was not limited to two dimensions or to a momentary impression. It was about creating something lasting, even timeless.

Most importantly, I learned about the world. From my hometown I knew only the Parmatown Mall, anchored with Higbee’s and May Company. Massimo taught me about the Galleria in Milano. I learned about architecture, fashion, food, literature, life. It was with Massimo that I had my first taste of steak tartare and my first taste of stilton with port. Imagine, raw meat for dinner and cheese for dessert! For Massimo, design was life and life was design.

Finally, from Massimo I learned never to give up. He was able to bring enthusiasm, joy and intensity to the smallest design challenge. Even after fifty years, he could delight in designing something like a business card as if he had never done one before.

It was Massimo who taught me one of the simplest things in the world: that if you do good work, you get more good work to do, and conversely bad work brings more bad work. It sounds simple, but it’s remarkable, over the course of a lifetime of pragmatism and compromise, how easy it is to forget: the only way to do good work is simply to do good work. Massimo did good work.

I intended to stay at Vignelli Associates for 18 months and then find something new. Instead, I stayed there for ten years. I loved my job. But I had finally reached a point where I realized I had to move on. Quitting was the hardest thing I’ve ever had to do. I had a speech all prepared, and the night before I was driving on Interstate 87 and rehearsing the speech in my head. Suddenly I saw the lights of a police car right behind me. I was pulled over. “Do you know how fast you were going?” “Um, 65?” “Try 85. You pulled up right behind our squad car” – it was a marked squad car, by the way – “passed us on the right, and then cut us off.” They made me get out of the car, checked the trunk, and took me to the State Trooper barracks for 90 minutes while they ascertained that I wasn’t a drug addict or a terrorist. Massimo had that kind of effect on people.

The next day, when I told him I had decided to leave, Massimo was the same as he always was: warm, emotional, generous. He had had many other designers work for him before me and would have many others afterwards. But for me, there would only be one: my teacher, my mentor, my boss, my hero, my friend, Massimo Vignelli.

Massimo died this morning at the age of 83. Up until the end — I saw him four days before he died — he was still curious, still generous, still excited about design. He leaves his wife, Lella; his children, Luca and Valentina; and generations of designers who, like me, are still learning from his example.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Michael Bierut

Related Posts

Innovation

Ashleigh Axios|Essays

Innovation needs a darker imagination

Business

Kim Devall|Essays

The most disruptive thing a brand can do is be human

AI Observer

Lee Moreau|Critique

The Wizards of AI are sad and lonely men

Business

Louisa Eunice|Essays

The afterlife of souvenirs: what survives between culture and commerce?

Related Posts

Innovation

Ashleigh Axios|Essays

Innovation needs a darker imagination

Business

Kim Devall|Essays

The most disruptive thing a brand can do is be human

AI Observer

Lee Moreau|Critique

The Wizards of AI are sad and lonely men

Business

Louisa Eunice|Essays