Julie Lasky, Annotated by Julie Lasky|Dialogues, Vignelli

September 15, 2010

Massimo Vignelli vs. Ed Benguiat (Sort Of)

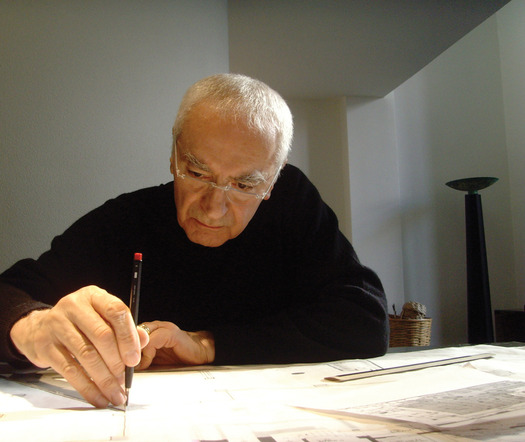

Massimo Vignelli (represented by Helvetica) faces off with Ed Benguiat (represented by Interlock) in a 1991 debate originally published in Print magazine.

In 1991, I was low woman on the Print magazine masthead, which meant I was responsible for much of the editorial grunt work. It was my job to organize a debate between Massimo Vignelli and the type designer Ed Benguiat that took place in our offices that spring. Afterward, I transcribed the tape and edited the transcript for publication in Print‘s September/October 1991 issue. Published under the rubric “Oppositions,” the debate was the second in a series. It followed “Tibor Kalman vs. Joe Duffy” — a 1990 dialogue about design ethics that was so notoriously cranky I didn’t feel the need to name names when I referred to its “antagonistic” participants in my introduction to its successor.

Print had brought Vignelli and Benguiat together because they looked like oil and water on paper. But rather than debate one another they surprised us by ganging up on Emigre magazine (1984–2009) as a symbol of the computer’s destructive influence on contemporary typography. What follows is an almost complete rerun of the 9,000-word original published version. Parts that have been skimmed away are indicated by ellipses (…). My annotations are oblique in brackets [like this]. Editorial insertions in the original published text are roman in brackets [like this].

— Julie Lasky

Last spring [i.e., April 1991], just as we were beginning to despair of finding two designers antagonistic enough to participate in another “Oppositions” debate, the phone rang. It was Joel Garrick, director of public relations for the School of Visual Arts in New York City, calling to say that SVA was sponsoring back-to-back retrospectives of the work of Massimo Vignelli, recipient of the school’s 1991 Masters Series Award, and Ed Benguiat, the distinguished type designer and lettering artist. Here was an opportunity for a lively debate, Garrick said, reminding us that Vignelli has championed the use of no more than six typefaces — per career — whereas Benguiat is one of the most prolific type designers of the 20th century.

Cheerfully agreeing that this was a match made in hell, we invited both men to our offices. They looked placid enough when they arrived one evening in April, but we put that down to good manners. [They may have been placid, but I was a nervous wreck. Vignelli was some minutes late, and I remember calling Lella Vignelli in a panic.] As chief designer of Photo-Lettering Inc., in New York, Benguiat not only creates hundreds of typefaces, but sells or consumes hundreds more. He is a typographic virtuoso (and, not coincidentally, a jazz musician) sensitive to the rhythms and modulations of culture. He wanted to talk about visual expression. Vignelli pays scant attention to cultural trends or self-expressiveness. Never having strayed from the values inculcated by his training as an architect and by his Swiss-born mentors, he approaches type with one idea in mind: its subservience to content and form. His own award-laden career has been built on a reverence for consistency, order, rationality, and harmony. He wanted to talk about visual pollution.

Once the discussion was under way, we wondered how our guests would conduct themselves. Would they assume an attitude of cool hostility, or let their emotions bubble to the surface? It didn’t take long to find out. Within ten minutes, Vignelli, no longer able to control himself, let slip that his opponent was “one of the nicest guys I’ve ever known.” And by the end of the two-and-a-half-hour debate (edited here for brevity), the opponents were planning a long trip to Sardinia together.

This pathological benevolence was a bit unsettling. As [the late and hugely lamented] moderator Philip B. Meggs, professor of design history at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, later pointed out, at times the participants actually switched positions and argued each other’s point of view. [For example, when Vignelli defended Milton Glaser’s kitschy Baby Teeth typeface, conceding he had never used it because he hadn’t “the opportunity.”] Moreover, the members of PRINT’s staff in attendance — editor Martin Fox, managing editor Carol Stevens, art director Andrew Kner, and senior editor Julie Lasky — had to work harder than expected to stir up a little controversy . . . or else come up with a kinder, gentler title for this series.

Thankfully, controversy did abound, as Vignelli and Benguiat joined forces to revile current styles and directions in typography, and to discuss the evil the Mac can do. — JL

Philip B. Meggs: I was fascinated when PRINT told me they were going to have a debate between Massimo Vignelli and Ed Benguiat and asked me to moderate. Very few individuals have influenced the history of American typography and design as much as the two of you have, or have received as much recognition and honor from the profession.

I think I’m on pretty safe ground when I say that your contributions are, philosophically and esthetically, very different. In fact, you represent two of the major poles in contemporary American graphic design. Ed Benguiat, you are primarily known as a typeface designer, who, as the head designer at Photo-Lettering, Inc., has drawn hundreds of alphabets. [Photo-Lettering no longer exists. Its archive of 6,500 alphabets was bought by House Industries in 2003.] Your typefaces licensed by the International Typeface Corporation — including Benguiat, Souvenir, Tiffany, and Korinna — have been among the most widely used in the past two decades. As a leader of what the late Herb Lubalin called the American school of graphic expressionism, you are interested in expressiveness — even decorativeness — and are willing to give a typeface a bit of the Victorian from time to time.

Massimo Vignelli, you have also made a considerable contribution to the evolution of American graphic design over the past quarter century, but as part of the other current: Modernism, or the European influence. When you were creative director of Unimark International during the ’60s, you probably did more than anyone else in what has been called the “Helveticazation” of America, converting countless major corporations — Ford, Alcoa, Memorex, J.C. Penney —

Massimo Vignelli: American Airlines.

PBM: American Airlines — to Helvetica and grids, to name just a few of the dozens and dozens. Over the course of the ’70s, after Unimark’s partners went their separate ways, and Vignelli Associates opened in Manhattan, you expanded your typographic range from Helvetica to maybe half a dozen typefaces.

I’d like to start by asking Massimo a question. Why did you limit yourself to just one typeface, Helvetica, for so long?

MV: We have to go back to the ’50s when we talk about that, and the kind of anxiety we had waiting for a typeface that would have no shoulder. As you know, all the old [metal] type until Helvetica had a lot of shoulder around the letter. We were cutting space between the letters and between the lines to get a more compact column. Akzidenz Grotesk was already there, but Helvetica was sort of an Akzidenz Grotesk with a narrow shoulder and modifications of a few of the letters. And that is really why it took off like a fire. It responded to a need which was there.

Now the need was … objectivity. As you know, the pendulum between objectivity and subjectivity is continuously swinging, and in the ’50s and ’60s it swung in favor of objectivity. We approached type, printing, typography with a reductionist attitude and tried to get rid of anything that was in the way. As a matter of fact, our philosophy at that point was that you needed only one typeface. And the only one which would do was very legible; it had different weights and heights; it had a very high x-height, as opposed to all the others, which had giant ascenders, as if they were trolley poles fetching electricity from some unseen wire in the sky.

For us, Helvetica was the absolute type. Objectivity is a search for absolute values, just as subjectivity is the search for relative values. And therefore, the whole search was for a typography which would be based on the meaning of things. (This was generated by semiotic thinking before semiotics came about as a label.) The other reason we were using Helvetica was because it allowed us to do the kinds of things we wanted to do. At that point, the most important thing was the relationship between different scales of type and spacing, and therefore grids.

PBM: But then, after you made that decision and used Helvetica exclusively, all of a sudden, in the early ’70s, you started using other typefaces. What happened?

MV: A lot of things happened in society at that time. You cannot live in a society that’s in transition and not have that influence you. At the end of the ’60s, there were the flower kids coming up and Haight-Ashbury and the Beatles and the whole [counterculture] thing.

PBM: So did you start using psychedelic lettering?

MV: No, that never happened, but you begin to reassess a lot of values. Also, I was seeing that the whole culture, the whole visual aspect of lifestyle, was moving toward junk very quickly — as opposed to classicism, which was always the search for perfection: absolutes, elegance, proportion. You know, when your mind expands with drugs, all those great values disintegrate very rapidly, so that once you’ve done a little finger-painting, you think you have done a masterpiece. That was the shallow mess of the generation of the flower kids.

Nevertheless, it was an opportunity for new things. It was not that I ever went in for subjective approaches, but you saw the pendulum switching around, a cult of contradictions and ambiguity (which is very related to my own Italian culture) beginning to pop up after being repressed by Swiss grids. And you began to see the historic advantage of using a little more. Therefore, Garamond came in; I had used it all the time even before Helvetica — it’s a very strong, elegant typeface. And Bodoni came in. And then I also started to use Century, because I was doing a newspaper at that time and it was a good typeface for that. And then I began to use Times Roman as well, for the same reason. And that was just about the end of the game. I mean, you never caught me using Broadway, or anything like that.

Ed Benguiat: You ought to try it sometime.

MV: For one word I could use it. If I had to do a package I might very well use it, or anything else that is appropriate.

PBM: What about Souvenir?

MV: Most of the work I’ve done in my life — good or bad — has been for architects, designers, museums, furniture companies, developers. If I had had a different kind of clientele, probably I would have developed in a different way, using different typefaces, because we strongly believe in appropriateness. When I say I used only five typefaces, it’s true if we look at the entire production as a whole. But here and there, we use of little of other things.

EB: I don’t know about that “here and there.”

MV: One thing that should be understood right away is that I welcome this debate because it offers the opportunity for bringing up a lot of issues which are dear to me right now and which have to do with a moment of transition we are going through in relation to computers, and so on. And it also should be understood as a great opportunity because it gives me a chance to talk to Ed, who, first of all, is one of the nicest guys I’ve ever known, and that helps a lot. But besides that, I do respect his craftsmanship tremendously.

Now in the case of influences, I remember when I came to the States, I thought that Herb Lubalin was the best thing that this country ever had in terms of graphic design, but was also the worst danger. His graphics were absolutely personal, and therefore only he could do it. Meanwhile, I was advocating a kind of typography which was nonpersonal and therefore could be used by many people, regardless of their degree of talent. Of course, it could be bastardized by someone who had no talent. That happens everywhere. But Lubalin’s direction was very, very slippery ground. It was like drugs: fascinating but lethal.

PBM: How do you feel about that, Ed?

EB: First I have to say that I didn’t design Souvenir.

PBM: Okay, you developed the family based on the alphabet that Morris Fuller Benton designed earlier in this century.

EB: I think it’s pretty difficult to assume that a person like Herb Lubalin could be a danger. Everything is a danger. We can turn our backs on it, but sometimes something good comes of it — anther Herb Lubalin, possibly; another Rembrandt; another Michelangelo. (I’m referring to people who are well known, for the purposes of circulation and readership: they all used to work up at J. Walter Thompson.) I think if one good thing comes of the typography Herb Lubalin was into — and it was personal — to me, that’s enough. I don’t think I would want to revert to the classic, as you do, Massimo. I’m not trying to be negative: you like blue, I like yellow. I like Jell-O, you like chocolate pudding. I would like to think that if Beethoven, Bach, and Saint-Saëns were alive today, they would redo the things they’d done before, or create new things out of what they’d done before, using all of the stereophonics, all of the sounds, all of the chords available. And I think this is what our society needs.

By the bye, I am a designer of letterforms as a business. I mean, let’s be realistic. When the psychedelic period arrived in the ’60s, man, I made psychedelia until everyone, including Timothy Leary, wanted it. My profession is designing alphabets for this new thing, the computer. But I have another profession: I do about 20 logos a year — I’m talking about big corporate identity stuff. I wouldn’t use psychedelia for that; I only use three typefaces too, you know: Helvetica, Helvetica, and Helvetica.

Now, I must wear two hats: being responsible and making money. And my responsibility is to give the public something that is good. It must be good, or they’re not going to buy it. What do I do? I’m not here to reverse what you said, Massimo, but, hey, we all have clients who say, “Move this stuff left,” even after you say, “Look, if you move it to the left, you’re going to ruin the whole layout.” What do you do?

MV: I fight.

EB: Oh yeah, we all fight. It shouldn’t be that way, and I think that people give us this work because they respect our capabilities. But every once in a while, these things happen. Many of the typefaces I’ve done were requests from Aaron Burns, Herb Lubalin, Ed Gottschall, Ed Rondthaler, or myself.

MV: I want to go back for a second to the notion of quantity and quality. Ed was talking of quantity, and he’s right, because the purpose of industry is to make a profit. This is why typefaces used to be done in very small quantities — very few kinds of typefaces — up to the beginning of the industrial revolution When the industrial revolution started, from 1775 on, let’s say, the amount of offering increased tremendously to corner market sections, and therefore increase business.

It is a sad condition of our culture, however, that the advancement and proliferation of technology is not paralleled by that of quality. Instead it’s paralleled only by shallowness — fragmentation of the quality into such tiny little bits that it can hardly be seen anymore, or hardly be found. But this is a process that started with industrialization. It’s an unfortunate thing, but it’s irreversible. There’s nothing we can do about it. We can only complain. At least, looking back helps somehow to guide us for the present and the future.

PBM: Ed Rondthaler, who founded Photo-Lettering and was one of the founders of International Typeface Corporation, once said in a lecture that there should be one place that stocks every typeface any designer ever dreamed up. That place, he said, is Photo-Lettering. How do you feel about that, a company which makes anything and everything?

MV: It’s a business. We have used Photo-Lettering for a thousand reasons since the first day I came to the U.S. I might need a typeface more condensed than is available; Photo-Lettering always did it very well, I must say. You’ve got to understand that when type was made with lead, there was very little need for that kind of thing. And when the possibility of photo deformation, or photo elaboration, of typefaces became available, then of course a new market came about, a new realm of things. And now we have personal computers with fonts and the damned thing in the computer that allows you to distort and manipulate type at your whim without any knowledge about type. Ed can do anything that he wants to with type because he knows type so well that he makes music out of it, not matter how. He can play the instrument. The problem is not him….

EB: There are three ends in the world of computer typography, and of design as well. There’s the high end, meaning those who know, or should know. Then, there’s the middle end; those who think they know. And then there’s the bottom end: those who don’t know at all. And people in every one of those categories think they are designers with typography.

MV: It wasn’t like that before. Now they’ve got to have a tool that gives them the license to kill. This is a new level of visual pollution. And this is why I feel personally committed to fight these things. At a lecture I was giving at the School of Visual Arts, I said that I can live with this kind of thing. You can. Everybody in this room can. But a five-year-old kid growing up today in this society doesn’t know that this is bad type. [Just pointing out that the five-year-old is now 24. Is she really less typographically literate than the professional of a generation ago?] And you know what we have done by that? We have lowered our level of civilization and culture another step, and that is exactly what we’ve got to fight.

Which brings me to the next statement. We think of ecology in terms of trees, gas, pollution, and so forth. But that is the first step. As a matter of fact, I think the end of the Gulf War, 1991, is the beginning of the new century. The 1900s are gone, and what we have right now, as the first sign of the new century, is what I call eco-ethics. It’s a whole new attitude about the world and our environment and the protection of our culture. This kind of typography has happened for a thousand reasons. There is a mechanism that allows it to happen. But there is also a lack of caution. Why do I not react like a state apart? Because I have a kind of caution that prevents me from doing it. Why don’t I go kill people? Because I’m in a culture that prevents me from doing it. Why don’t I rob people? Because I’m in a culture that prevents me from doing it.

PBM: Is there an antidote for this illness?

MV: Yes — awareness. Raising awareness. Fighting, talking, preventing….

PBM: You said the answer is education, and I would assume that would start in the design schools.

MV: Yes, absolutely.

PBM: Design schools all have typeface-design software now. I’ve pulled out of Emigre magazine two typefaces that come from a couple of our top schools —

MV: Take that disgraceful thing called Emigre magazine. That is a national calamity. It’s not a freedom of culture, it’s an aberration of culture. One should not confuse freedom with [lack of] responsibility, and that is the problem. They show no responsibility. It’s just like freaking out, in a sense. [Originally, Vignelli, who seemed unusually preoccupied with hallucinogenics that evening, said, “It’s just like freaking out on drugs, in a sense.” My boss, Martin Fox, was nervous that Rudy VanderLans would be provoked to sue Vignelli (and Print) for defamation and insisted that I remove “on drugs” from the published transcript.] The kind of expansion of the mind that they’re doing is totally uncultural. [To Benguiat, who is laughing] This is why you react this way. It’s not because it’s progressive and you’re conservative. We are conservative in a sense, but we want to maintain a level of quality that hasn’t changed from the Roman times to the Renaissance to the 18th century to you name it. In Malevich, there is great quality. This is why his work is still alive; this is why it’s timeless. This [shaking the Emigre page with the typefaces] is garbage, and Emigre is a factory of [typographic] garbage. [The addition of “typographic” to the transcript was another nervous gesture on Marty’s part; he wanted to put some drag on Vignelli’s ferocious rhetoric. “Factory of garbage” without qualification was getting dangerously close to poetry.] This is what is offensive to me. We cannot put garbage on a pedestal; just because it exists does not prove that it is quality.

PBM: Pardon me, Emigre has won some important design awards. Why is it garbage?

MV: Maybe you should be one of the design judges. I refuse to go into any more AIGA judgings because of the amount of crap you see. Listen, just to give a quick example, I judged one of the last AIGA Communications shows. There were three judges, me and two young ladies. [The jurors listed in AIGA Graphic Design USA 12 aren’t broken into categories; the women participating that year were Sandra Higashi, Jane Kosstrin, Nancy Rice and Debra Valencia. Pick two. Or perhaps the “ladies” would be willing to step forward at this juncture?]. Would you believe that they were turning down posters by Paul Rand? Hey, wait a minute. Paul Rand has never one day in his life done a bad thing. Never! And they were good things. But they were not the extremely kind of shallow stuff which the others were pushing. I was in the minority all the time. These two girls turned down Paul Rand, Milton Glaser, Seymour Chwast. Perhaps that’s the old guard. Fine. But the new guard was nothing but real trash, Listen, I adore April Greiman. April has a great quality. She’s not trash. But, Jesus, you should have seen this.

Martin Fox: What’s the difference in your opinion between what April Greiman does and what Emigre does?

MV: It goes back to what I said about Herb Lubalin. I think that April’s work is very personal. It’s not expandable. Emigre deals with subcultures instead of cultures. It deals with deformation as a thing to look for rather than reject. In other terms, Emigre is scooping in the trashcan, where everything has already been discovered and is out of use and has no purpose anymore. Now keep in mind that the objet trouvé, the idea of finding a great thing out of a mistake, is very difficult in this culture. It’s a Victorian kind of projection. It has no logic. It isn’t a man-made culture. A man-made culture is the culture of classicism. That is opposite to the romantic culture, which defines beauty in the happenstance. Now these guys at Emigre find beauty exactly in the junk — the type of deformation that the computer is provoking.

PBM: Ed, let’s hear from you about Emigre….

EB: The only comment I have about Emigre is that when I look at it, I’m uncomfortable typographically. [He was uncomfortable every which way with the the turn of the conversation, as can be seen from this and all of his subsequent efforts to reroute it to more familiar turf.] That’s enough for me. I’ve looked back at old Harper’s Bazaars and Vogues when they were doing the psychedelic look. They were trying to cash in on what the public wanted, but that didn’t disturb me as much as Emigre does. We’re dealing with taste now.

Andrew Kner: No one brought up the word readability.

EB: Do you really want to bring up that word?

AK: Yeah, because I think maybe at the root of what you find disturbing about Emigre is that it is unreadable, whether or not the page is esthetically beautiful.

EB: Maybe. I think that readability, legibility, is something people are overlooking. A lot of graphic designers don’t know what good readability is. I find that Paula Scher’s work is also unreadable; by the time you get to the end of the word, you forget what the first two letters were. I’m not being facetious. This is a look, and very widely letterspaced words just don’t flow. Yet she happens to be a very fine designer and it doesn’t disturb me.

MV: I think we have to make a distinction between design and art. If you are an artist, you can do anything you want. It’s perfectly all right. Design serves a different purpose. If in the process of solving a problem you create a problem, obviously, you didn’t design. Most of the time, what you have done is neither art nor design. And that is exactly where most of production done today falls: it’s neither one nor the other. The other thing that bothers me is this culture of revivals, which, again, is typically Victorian. Now this amazes me. Do you realize that, for all intents and purposes, we’re still in a Victorian kind of culture in this country, where it is neo-everything all the time. The main reason Constructivism and the Bauhaus came about was to fight this culture of revivalism.

PBM: I’d like to hear what Ed has to say about revivals. Tiffany is based on a typeface that has a bit of Victorian decorativeness —

EB: Caxton, yeah.

PBM: And you were involved in a new edition of that typeface, developing a whole new family of weights.

EB: I don’t call Tiffany a revival. I call it a merge of two typefaces, Caxton and Ronaldson. I think revival is to take a typeface like Garamond, which is so mixed up in photo because the x-heights of each alphabet are different, and have a person like Tony Stan come along and say, “Hey, we’ve got to settle this down.” I did the same thing with Bookman. Bookman only had one weight and a drawn oblique, not a camera oblique. Someone had to come along and revive it in a different weight. So the word “revival” to me also means to take what exists already and put it into working order. Souvenir is a good example of that. It became a workhorse. And Helvetica was a workhorse. When Max Miedinger [Helvetica’s designer] came to visit me, he drew only three Helveticas. I drew the rest of the original six.

MV: For the Haas foundry?

EB: No, for Photo-Lettering. Max Miedinger, who was from France [actually, he was Swiss], was fired after he drew those three faces. And his salary for the one-year period was $5,000 without any royalty.

PBM: Why was he fired?

EB: They didn’t need him anymore.

AK: It’s interesting that Massimo has limited his typefaces, but some of them are in a sense revivals. I mean, Century is a 19th-century face and Bodoni is a late-18th-century face. Perhaps we’re the only century that uses earlier types.

EB: What’s going to happen in the 21st century? They’re going to call the typefaces that I and others have done classic faces and someone is going to come along and revive them. “Modern” means nothing more than of the time.

I have a question for you, Massimo. Do you think the world was waiting for another Bodoni when you redesigned it? I don’t think the world needs it. But I think what you have done is a wonderful thing: Bodoni needed a fix-up. The Trajan Column in Italy is being repaired. And the crack behind the finger of God in the Sistine Chapel has been fixed, you know, otherwise the whole wall would have fallen down. I have to give you credit for repairing Bodoni without destroying its integrity.

PBM: How did he repair Bodoni?

MV: When Helvetica came about, it had one great thing, which I mentioned before: a high x-height and a lower cap height. With all the other typefaces we use, however, the x-height is very different. Some, like Century, have a high x-height; some, like Garamond, have a very low x-height. We wanted to take Helvetica as a master, because it reflects our taste in type and use, and then have a Bodoni, Century, Futura which are all compatible. But it’s a job to do that properly.

EB: There’s a tremendous problem here. See, I added a touch of cream, but now I have to add a little sour cream to it. There are the buffs out there — I know many of them — who say, “I don’t want you to give me the Bodoni you’ve made. I want the real Bodoni.” I think our society — and I’m part of it — is destroying what the old metal type looked like by doing just what you did to Bodoni. We are destroying the integrity and the fineness of the craftsman.

AK: The technology has changed.

EB: Yes, but they could scan [the original] and leave it just as it is, one on one.

PBM: Aren’t you contradicting yourself? Earlier, you commented on Tony Stan’s fix-up of Garamond.

EB: Well, that needed it. The heights were all wrong. Each alphabet was all messed up. Some of them were done over 200 years, from Granjon all the way up, with each person getting their finger in it. It was like five people cooking a pie at 50-year intervals — the same pie.

PBM: Do you use ITC Garamond?

MV: Yes.

PBM: That’s interesting. Paula Scher hates ITC Garamond.

Kner. She says the x-height is too high, exactly what Massimo was saying he liked.

EB: She built this attack against ITC for destroying Bookman, which I had worked on. She was right. I did destroy the original face. It had to be destroyed because Bookman has the waist of the lowercase e a little high. It’s that classic look. When you get to the heavy weight, if you make it high, the negative space is gone. So you lower it a little bit. And then you look at the first one and say, “That one’s high and this one’s right in the middle. I think maybe we should step it up; let this one be in the middle.” And then something goes wrong. They don’t look the same. Well, there was never a bold Bookman.

AK: Not in the original cut.

EB: Paula was right. But she used to call up type shops and say, “I’d like the real Garamond” — metal — without realizing that she wasn’t getting the real Garamond even then. She and I have known each other a long time; we’ve discussed it. The fact that the type shop took the real Garamond and just printed it on a piece of paper and she statted it, ruined it.

AK: The point is which real Garamond do you want? ATF real Garamond, or Bauer, which also cut a Garamond?

EB: And none of those are the real Garamond.

PBM: The real Garamond would be — what?— the 1534 Claude Garamond, which no one would use because his technology was so crude.

AK: It’s all been recut, even by the metal shops. But I think that the philosophy here — I mean, besides the technical aspects — is what’s so fascinating. In late-20th-century design, we all use typefaces that are 200 years old. So which ones are correct and which ones are not?

EB: Andy, someone wrote an article — I think it was a letter to the editor in your magazine — that said when you use an Ed Benguiat typeface it’s like you’re in the ’50s or ’60s ‘cause that’s when it was designed. I said, “Gee whiz, I guess when you use Bodoni, you ad would look like the 18th century — I’m sure Paul Rand would appreciate this.”

We’re all using classic faces, but they never had the weights one needs. They never even had italics. And that is a gripe I have: taking roman letters and obliquing them. Designers think italic is anything you slant….There is no such thing as a sans-serif italic, yet we all have been ordering it for years. What that is is an oblique letter modified to even the weights out, but it isn’t italic. A true italic letterform, when drawn to be an italic in the serif alphabet, has to have a tail in the lowercase.

MV: So you condemn obliques?

EB: I condemn all obliques.

MV: What about Helvetica italic?

EB: I condemn it because I think sans-serif letters that have been obliqued are an atrocity of the machine age in typography.

AK: So what would you suggest?

EB: Since this is on tape, I suggest you leave it the way it is ’cause I use a lot of Helvetica italic. And I use a lot of Futura italic. But if we’re going to talk about pollution, then we have polluted Futura by putting it into an oblique. By the way, Bodoni italic was drawn incorrectly because the last few letters of the original face were not drawn by him and no one changed them.

AK: Phil had a terrific point in his introduction that I’d like to go back to. He mentioned the two basic styles of design that have coexisted in this country since the ’50s and ’60s — the European influence and American expressionism, which I guess is also called Pushpin style. They — Pushpin — revived not only the classic typefaces we all use from the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, but typefaces which had been totally lost. They brought back these crazy 18th- and 19th-century faces and used them in entirely fresh ways, not imitating the 19th century but certainly using the elements. Now, what do you both think about that? It’s not classical typography. It’s not reviving. It’s something else.

EB: Especially if you’ve worked in a publishing company, trying to get a particular mood for a story, you know the feeling of wanting to use a typeface that nobody ever saw before. You had these books of type that was no longer available, and you said, “This is what I want.” For example, Card Mercantile was a beauty, and then there were these condensed British grotesques. Well, Photo-Lettering started doing this, too. But we always had — within this framework of taking the old and using it either in an old way or in a new way — designers like Seymour Chwast who came along and said, “I think I’ll draw a typeface and call it ArtTone.” And Milton Glaser doing Baby Fat, Baby Teeth, Dingleberry.

PBM: Is this visual pollution?

EB: Yes. [Huh?]

MV: No, I think whenever it has quality it’s okay. [Huh?]

EB: No, that was visual pollution.

MV: I think Baby Teeth has a lot of quality.

PBM: Have you ever used Baby Teeth?

MV:. No, but I never had the chance.

AK: If it’s used well and it’s a typeface one might use once in a lifetime, is that visual pollution?

EB: Well, the others come along, and in an attempt to use it well, they use it badly.

MV: From my point of view, one of the most unfortunate things that happened in the ’30s was the exhibition called “International Style” at the Museum of Modern Art. It was the official introduction of modern architecture in the U.S. In Europe, however, the movement didn’t develop as a style; it was a revolt against the philosophical issues of the Victorian time — all the early stages of industrialization when profit was the only motivation for doing things. When the Modern movement was born in Europe, it was really to provide alternatives that were rooted in the essence of the new time. This was exactly the same kind of philosophical change that happened in the Renaissance. When the Modern movement arrived in the U.S., it came during the [Depression], and it came packaged by MoMA and put together by people who have throughout their life switched from one style to another. That’s what Philip Johnson has been doing. He went from classicism to Mies-things to gothics. Once, I visited his office and on one desk they were doing things in a neo-romanesque style, and on another a neo-gothic skyscraper, and on another a deconstructionist building. I thought I had made a wrong turn; I thought I was in Bloomingdale’s.

In other words, when industrial design was born in this country, it was born not as the answer to industrialization — not as a working things out according to the tools and the issues and the problems — but basically as an incentive to sales — exactly the same kind of thing which has been done by a lot of other people.

AK: Perhaps we’re misunderstanding what the diversity of American culture is all about. My wife and I were in Italy with our kids when they were quite small and we had a marvelous time; and then we were going to visit Hungary, so we got on a bus in Venice after lunch, and went to Austria. And when the bus stopped three or four hours later, and we had dinner, the kids wanted pasta because they loved pasta. Well, you can’t get pasta in Austria; it’s a different country. The kids were too young to understand that they had crossed a border, because in this country, of course, you can get pasta anywhere. And if you don’t like it, you can go around the corner and get Chinese food.

MV: Americans don’t know what it’s like living in a mono-ethnic society. This is why I can’t stand going back to Italy. This is the first pluralistic environment that happened in the history of man.

AK: This is a multi-racial, multi-religious society. But doesn’t the typography we’re talking about reflect that?

EB: Absolutely. You’ve banged it exactly right. You can go around the corner and get type from any place you want. I’m not talking about just around the neighborhood; you can get type designed in England, France, Germany, Italy, Spain. I’d also like to say, speaking of modernism, that I never in my life concerned myself with this kind of design or that kind of design. I looked at Paul Rand to see what he was doing. I looked at the annuals of the Art Directors Club. I only concerned myself with the people who were in my circle. I remember when Pushpin had just started up and Seymour [Chwast] asked me to work on something that turned out to be the Pushpin Almanack. You know, these were young people who were in their own world doing what I was doing. We did not in any way try to do anything typographically except use typefaces nobody ever saw before.

PBM: Is there a parallel between what you and Chwast and Milton Glaser did back in the early ’50s and what Emigre … are doing with their typefaces?

EB: Well, they’re in their world, just as I was in my world. The thing is this: I’m not going to say whether what they’re doing is good or bad. I just don’t like it.

MV: I can say whether it’s good or bad.

EB: I won’t, because tomorrow morning one of these designers is going to come up to Photo-Lettering and try to sell an alphabet on a royalty basis, and of course, I’m going to take it and stick it in our file. And next week probably Saul Bass will sell it to the telephone company. I have no idea what’s going to happen. But the fact that someone uses something or doesn’t use something doesn’t mean it’s bad or good.

Music is an area that I consider very close to what I do. Music has a lot of notes; alphabets have a lot of letters. I give you all the notes; write me a tune, I give you all the letters; do me a piece of typographics. Now, I can take this, create some graphics for you, right here, in this room, and send it to a show. And I’ll win an award. I’ll blow up each letter and put it in a square, dress it up with all of the glamor that our society wants to see. If you dress up something, you can sell crap — but only once.

AK: So you’re saying you can take the world’s worst typeface and sell it? In fact you can make a good design out of it?

EB: Absolutely. Let’s put it this way: Isn’t it wonderful that our society is so gifted at selling crap that I buy it and you do, too?

PBM: Massimo, we’ve talked about visual pollution, but now you’re praising the pluralism of American culture. Isn’t there a contradiction there?

MV: The fact that we have pluralism is a terrific thing. It’s the nature of the country. It’s the nature of the cultural output. The fact, however, that this cultural output is not as high as it should be is another, completely different, matter. So I think that out of this plurality of people, the common efforts should continue for the improvement of quality at every level.

PBM: Do you see yourself as a guru in the face of this vulgar crass American culture?

MV: But it’s not! You go to Italy, the country of design, and you see more junk there than any place else in the world.

MF: Doesn’t a multicultural society demand something to hold it together that’s common to all, so that you would want — particularly in the area of communication — fewer modes of communication?

MV: No, I think that would be a mistake. If I liked only people who do things the way that I do it, that would be very limiting and uninspiring. Pluralism of expression is fine, but not pluralism of junk. All of the guys we’ve mentioned — Lubalin, April Greiman, Pushpin (and especially Milton Glaser, who is a great, great guy) — are high-quality people who put a lot of thinking behind what they’re doing. And what I appreciate most is their value of expressing meaning rather than non-meaning. What I’m opposed to with these other people — what’s their name?

PBM: Emigre.

MV: What a name! What an insult! I’m opposed to their lack of depth, this very shallow epithelial surface.

Julie Lasky: The way you’ve described Emigre makes it sound like what someone might have said about Dada in the ’10s and ’20s.

MV: No. Dada was just the opposite, as a matter of fact. All the Dada expressions were absolutely conceptual. They never had anything to do with the value of the artifact. Now, in this culture, it’s the other way around; we are completely involved with the value of the artifact and use that to express meaning. Therefore, we’re much closer to music. We like music and we can’t stand noise. What we see here in Emigre is noise. Noise is a sound that has no intellectual depth.

AK: Dada was a reaction to Europe after World War I, where everything seemed to have lost all meaning. The only response was to create art that seemed to destroy the meaning of objects. There was as strong philosophical underpinning. But isn’t what you object to in Emigre, Massimo, that it picks up some of the surface aspects of Dada without the cultural underpinning? There’s no communication there, but there’s no reason for there not to be communication.

PBM: I’ve talked to Rudy VanderLans, and I perceive him as a person who is attempting to develop new ideas and to respond to new technology by seeing, for example, what can be done with a low-end dot matrix printer. And I think he sees the design establishment as being a little bit fossilized.

AK: I don’t know him, but when you say he’s trying to test the new technology, what is he trying to communicate with it? I’m not asking this facetiously. I really don’t know.

EB: I think we’re getting too heavy here. You know this whole thing is a heavy problem.

PBM: Regarding this issue of legibility, why shouldn’t we conduct studies to identify the absolute, most legible typeface and just use that face?…

MV: One of the things I always say is that, for me, typography has very little to do with typefaces. Typography is structure. We structure the page, centered or flush left, or on a grid. And the lines we draw in are just lines; they’re not type. Therefore, to put so much emphasis on the type is out of place.

PBM: So you would be perfectly happy to have one typeface if it was the most legible, readable one?

MV: When you choose the type, you’re getting into something else. Each type has connotations different from another one. And therefore you begin to make a little communication in a certain way. This is the notion of appropriateness.

PBM: Okay, Ed. Why do we need so many typefaces? Why can’t we find the most legible readable typeface and just use it?

EB: Why don’t we find the most beautiful piece of music and just listen to that too? And why don’t we just eat the one piece of food we like? And why don’t we wear the same colors? Why don’t we have one Broadway show or one piece of poetry? The answer is just as simple as the question. Because.

PBM: Can you explain the “because”?

EB:. I feel that almost every type designer from the point when time began has wanted to create the ultimate beautiful, readable, and legible typeface. I have a personal need for the ones I design. I also design them because I need it for my job. I don’t think that our society would be missing anything if we only had one typeface ‘cause that would make life pretty easy. Then you could only pick one. But I would be out of business….

MV: I hate variety for the sake of variety. The amount of problems one has to address as a designer brings variety in itself: a variety of solutions. We see variety for the sake of variety from every point of view: architecture, clothing, printing, movies. And that is what is cheap, rotten, and greedy in our society.

MF: So you disagree with Benguiat!

MV: No. It’s not Ed Benguiat with his fantastic ability of doing thousands of different typefaces who is polluting. What it is polluting is the manipulation of type as it is done by incompetent people and is flooding the whole place now….

Carol Stevens: What do you think of a company like Adobe that puts typefaces out for everybody to use?

MV: I think Adobe is pretty good.

EB: In my opinion, the worst typefaces have come from there.

PBM: Why is that?

EB: Because of the quality control on the faces. It was an early problem. But now they have a new system and their typefaces will be better….

PBM: Let’s close with a question about future possibilities. What things should we be concerned about as we move forward into this new century?

EB: The most important thing that I can see is that education has to get its feet off the ground. I feel it’s my responsibility and the responsibility of other designers to do everything we can not to let students squeeze letters, because that can become the state of the art.

AK: You don’t think they will eventually discover what good typography is almost by accident?

EB: Never. As Massimo said, if young children keep seeing something like this, they’ll think a beautiful o, in a circle, is wrong. The only way to educate is to catch the student in school. I’m not saying go into calligraphy and all of that. It has to be on the level of typography. And it’s the job not only of the educators in graphics, but the educators in the world of computer-generated typography to put out a little something showing what good typography is. They could put programs out that would give you a condensed letter by pushing the button. Adobe is doing this now. An issue of Typeworld that I got in the mail yesterday said that from one letter, Adobe can give you 32 weights in 23 proportions without distorting the letter. That’s a beginning.

PBM: Massimo, what’s your answer?

MV: ….What they should do in school is learn what the classic typefaces are — or Futura or Helvetica — and draw them by hand, because that’s the only way to learn. You can show any one of these kids two typefaces, a Granjon and a Garamond, and they would not know the difference. So how can you become a professional in graphic design if you do not even know the tools you have to use? It seems to me what has to be done is to retrench from this meaningless passion for self-expression and go into knowledge. With knowledge, you get everything else. Without knowledge, you get nothing. With culture, you have freedom. Without culture, you will always be a slave. And that is basically what’s happening. So the most important thing for the new generation, in my mind, is to understand the value of eco-ethics, which implies the fight against obsolescence and the search for timelessness, for a culture that you don’t discard, things you don’t throw away. That to me is the new task.

EB: Maybe you and I should go to Sardinia, and we’ll just relax and let the whole graphics arts community sail themselves gently out to sea.

Coda: In Emigre #23, 1992, Rudy VanderLans wrote: “My friend, the designer Chuck Byrne, calls and asks if I’ve read the new issue of Print. I say no. Why? ‘Check it out,’ he says. ‘You’ll love it.’ Next day I’m at Cody’s Bookstore in Berkeley, and there it is. Inside, Phillip [sic] Meggs interviews Massimo Vignelli and Ed Benguiat, two New York design institutions. They agree Emigre magazine is garbage and then deploy considerable brainpower toward detailing what subspecies of garbage it is. Benguiat declines to appraise it too deeply: as if it were a bad smell or breed of cat; it’s simply a thing he doesn’t want in his house. But Vignelli has made up his mind and minces no words: Emigre is a national calamity. An aberration of culture. Yikes! Vignelli wasn’t kidding when he said he was in a fighting mood. I can’t figure it out. Two design gods devote part of their interview to trashing Emigre instead of showcasing their own work. I break out in a cold sweat. I am garbage. What does that mean?”

Nothing that couldn’t be recycled. In 1996, Zuzana Licko, Emigre’s co-founder and font designer, created Filosofia, her own variation of Bodoni. The designer of the promotional poster? None other than Massimo Vignelli. His headline: “It’s their Bodoni.”

Original text reproduced by kind permission of F+W Media.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Julie Lasky & Annotated by Julie Lasky

Related Posts

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Cinema

About face: ‘A Different Man’ makeup artist Mike Marino on transforming pretty boys and surfacing dualities

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Cinema

‘The creativity just blooms’: “Sing Sing” production designer Ruta Kiskyte on making art with formerly incarcerated cast in a decommissioned prison

History

Michael Bierut|Essays

Lella Vignelli

Graphic Design

Michael Bierut|Essays

Massimo Vignelli, 1931-2014

Related Posts

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Cinema

About face: ‘A Different Man’ makeup artist Mike Marino on transforming pretty boys and surfacing dualities

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Cinema

‘The creativity just blooms’: “Sing Sing” production designer Ruta Kiskyte on making art with formerly incarcerated cast in a decommissioned prison

History

Michael Bierut|Essays

Lella Vignelli

Graphic Design

Michael Bierut|Essays

Julie Lasky is editor of Change Observer. She was previously editor-in-chief of

Julie Lasky is editor of Change Observer. She was previously editor-in-chief of