Xanthia Hallissey|British Telecom, Essays

November 29, 2011

[MB][BT] In Phone, In Fashion

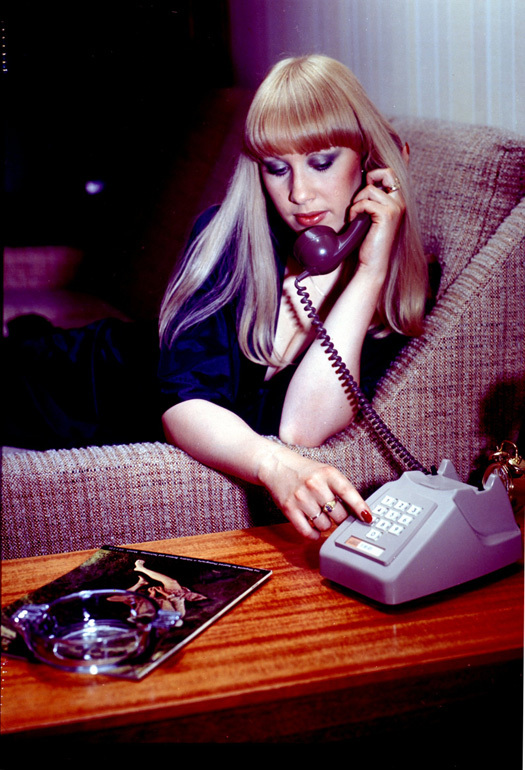

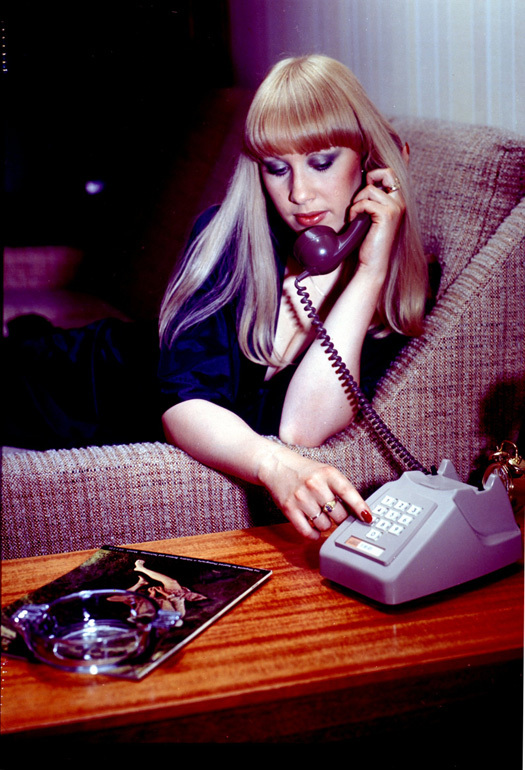

Women were included in 1970s phone catalogues to demonstrate the use of the phone. Little direct eye contact suggests a coyness, not to be mistaken for a lack of confidence. Image TCB 417/E 65861c courtesy of BT Archives.

Her smile is a weapon, every page is a hit. Welcome to my world she encourages, you can be like me. Photographed wearing only a towel she seems unfazed, her face shiny and make-up new. The photo lives inside a BT phone pamphlet, In phone. Inspired. In the Home. Held next to her hip is a phone called Genie. The phone has a name, but the woman does not. Genie is her magic ticket into the ‘In Crowd’. It’s clear what kind of woman you have to be to fit in, every page a different woman, every page the same face.

BT phone catalogues in the 1980s used glossy women to advertise their products. Prior to this; “phones were not very sexy”, regarded as functional items, the telephone was an important addition to the home but not exactly desirable. Rented from BT, customers were offered little aesthetic variety. It is this notion of choice that radically altered in the late 1970s with the redesign of the phone, away from the rotary dial, and the emergence of phone shops. The phone catalogue marked a new wave of promotional material for BT, positioning the phone as a desirable purchase. Colin Wise, part of the marketing team at BT, recognised how important this was in selling products. He initiated a new form of print advertising called “The Advertorial,” fashion editorial meets phone advert. Women became the point of sale “buy me.”

Phone catalogues in the 1970s depicted the woman as secondary to the phone, her presence was essentially passive, only necessary to show human interaction. The home was considered female domain, thus phone catalogues tended to depict women, the target audience. The models rarely connected with the camera in terms of eye contact, as if the woman’s natural behaviour was being observed. The women featured in the catalogues had a similar look, creating a taxonomy of “attractive” women. Constantly presenting the same type of woman projects an ideal consumer. In the ‘70s that idealized woman was typically blonde and wholesome looking with a well-presented house. In, Decoding Advertisements Judith Williamson reflects on how advertising works: “you must feel that you already, naturally, belong to that group and therefore you will buy it” (Williamson p.47, 1978). Advertising presents a glamorous version of reality, relatable but aspirational. In the 1970s having the latest phone in your house and the time and money to use it casually, would have been attractive prospects.

However, this “housewife” type imagery wasn’t always received well. The Women’s Movement in the same decade claimed that presenting women as passive was a reflection of patriarchal society, encouraging people to question the representation of women in the media. “What has characterized the modern women’s movement has been its ability to put everything up for discussion” stated feminist Jenni Murray (Murray 2005). For a modern audience, analyzing the representation of different social groups has grown in precedence. The confectionary company “Cadbury” were famed for “The Flake Girl” used in advertisements for over forty years. An “attractive” girl was always shown slowly eating the chocolate. In 2010 Flake produced a £1million advert, but it was never aired due to a negative audience reaction during focus groups. ‘Flake’ is an example of how the notion of what is seen as appropriate changes for every generation.

The passive women depicted in BT’s earlier promotional literature had no place in fashion magazines. The Advertorial initiative began in 1983, the magazine publisher Conde Nast wanted to fill space in their magazines and for BT to pay using their publicity budget. Aware this was a unique opportunity for promotion Colin Wise, BT marketing, agreed but made; “outrageous demands” taking advantage of fashion photographers and models instead of the in-house photography team BT typically used (Wise 2010). The photographs ran in publications such as Tatler, Vogue, Elle and Cosmopolitan, using prestigious photographers such as David Bailey, John Swannell and Terence Donovan. BT phones became fashionable, sexy even. Many of the photographs were then directly transferred into BT designed literature, particularly the ‘In Phone’ series. Fashion advertising works by selling you something that you don’t need, you want. Using this formula phones made the transition from functional item to stylish commodity, “if you wanted to be with the In Crowd you needed an In Phone” (Wise 2010).

Models are essentially acting; they sell a lifestyle that seems attractive. The BT fashion promotions were like any other editorial spread in the 80’s, showing fantasy images of powerful, sexy women who happened to be holding a phone. Overpowered by the magnetism of the model, the phone is rendered almost invisible, it is not important whether the phone actually works but the way the woman acts around it. Sex appeal was a driving force in the images created during this time, sexual expression was tied with ideas about liberation. A change in attitude can be observed through the woman’s mouth, often lipstick adorned and open, becoming an invitation. BT was selling women, to women, but not necessarily in terms of sex appeal. Modelling could be regarded as aspirational, one of the few industries in which women could reach the top and outperform male counterparts.

In Retro-Sexism Judith Williamson wrote that sexism is “regarded as a part of life” arguing that people accept a certain amount of sexism as normal (Eye magazine p.52, 2003). Adverts are a social document, showing an interpretation of reality never too far away from peoples hopes and aspirations. This certainly remains relevant in how products are sold now, it is the lifestyle attached to a product which is the desirable factor. The ‘Flake Girl’ example shows a challenge to a previously accepted taxonomy, highlighting how important it is to constantly re-evaluate the media images that bombard us. The women photographed in the 1970s may have been at home in the kitchen, but at least they weren’t photographed kissing the phone. An advert is a reflection of its time, and sexism meant something different in the 1970s than in the 1980s, let alone what it might mean to us now.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Xanthia Hallissey

Related Posts

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

The Observatory

Ellen McGirt|Books

Parable of the Redesigner

Arts + Culture

Jessica Helfand|Essays

Véronique Vienne : A Remembrance

Recent Posts

Mine the $3.1T gap: Workplace gender equity is a growth imperative in an era of uncertainty A new alphabet for a shared lived experience Love Letter to a Garden and 20 years of Design Matters with Debbie Millman ‘The conscience of this country’: How filmmakers are documenting resistance in the age of censorshipRelated Posts

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

The Observatory

Ellen McGirt|Books

Parable of the Redesigner

Arts + Culture

Jessica Helfand|Essays