April 30, 2014

Muriel Cooper: Messages and Means

Several works by Muriel Cooper form a small but important exhibition, “Messages and Means,” at Columbia University, and cover 1952 to 1994, the years when she profoundly changed the look and feel of graphic design. It should be required viewing for those interested in the field. Or really everyone who texts, tweets, or uses social media networks. Cooper dedicated her career to the creative potential of technology. Reworking graphic conventions, her tactic negotiated the transition of print into the digital realm that has left a lasting legacy in the constant flux of digital imagery we consume daily.

This singular mini-retrospective moves easily through the roughly three phases of Cooper’s career: graphic designer, researcher, and educator. Cooper, who was born in 1925 in Massachusetts, earned design and education degrees from Massachusetts School of Art, and started out with her eponymous firm and then as a freelance designer in MIT’s Office of Publications in 1952. A Fulbright fellowship led her to Milan where she developed interests in layering, transparency, and abstraction conjured by the works here.

“The Bauhaus” book (1969), or “Bauhaus Bible” as it is often referred within the industry, is probably the most instantly recognizable. One of more than 500 publications she produced as the first design director of MIT Press (she also designed their logo made of vertical bars in 1963), the epic book — still in print — offset each primary colored plate in the title. Rendered in giant Helvetica font, it makes visible the layered gestures of the creative process. Promotional posters and announcements accompany a copy that visitors can flip through. Cooper also made a stop-frame animation of each page of the book using a 16mm camera, which suggests her fluid and filmic approach to the printed page that nicely presages her conversion from print to information environments.

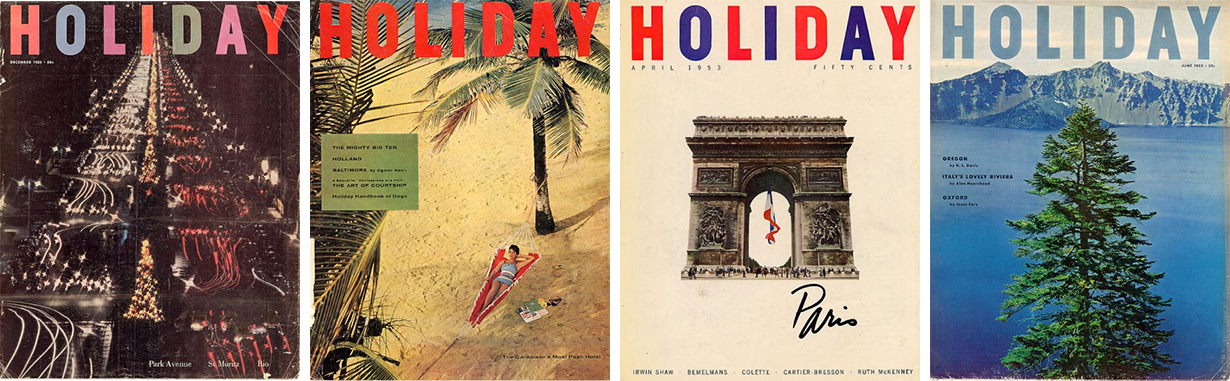

A section dedicated to book covers includes other notable additions such as her design for “Learning From Las Vegas,” Denise Scott Brown, Robert Venturi, and Steven Izenour’s seminal post-modernist text from 1972, which broke with the rigid grid system. The original edition, also with a bubble-wrapped dust jacket over fluorescent dots — “in homage to Las Vegas glitz,” remarked Cooper — was unfortunately abandoned by the authors and replaced with one that bears little resemblance to Cooper’s more avant-garde format. A series of her preliminary mock-ups are not to be missed.

Cooper’s greatness is undeniable, and in the works on view at Columbia University, it is unusually accessible. Well-installed and smartly curated by David Reinfurt of Dexter Sinister and Robert Wiesenberger, a PhD art history candidate, this exhibit does a lot with little space. The work is loosely arranged in two parallel rows, with many printed materials sandwiched between plexi-glass panels designed by Adam M. Bandler and Mark Wasiuta, that suggest the constant flow of information that dominates the way we process images today. And much in the vein of Cooper herself, the media are mixed.

Cooper reformulated the field in radical ways to make a point about the modern world’s shift from print to digital. Her work sought more responsive systems between design and production, between thinking and making. At the Visible Language Workshop at MIT, which Cooper co-founded in 1974 along with the physicist Ron MacNeil, she and her colleagues and students presented advanced research projects experimenting with computer data visualization. Hands-on production and an attitude of access to new tools (they often created their own) included color xerography, photographic chemistry, offset printing, thermography, digital-typsetting, and eventually elaborate electronics and computers. These defined the workshop, now the MIT Media Lab, and are demonstrated through the letterheads, dummies, drafts, and catalogs on view in the show. Two film clips located in an alcove off the main hallway of the exhibit give prominence to the designer’s later work in computer interfaces and artificial intelligence.

A highly regarded professor until her untimely death in 1994 at age 68 (she was the first tenured woman at MIT Media Lab), Cooper was a potent inspiration for younger generations, many of whom became design pioneers themselves — the late Bill Moggridge, co-founder of IDEO; Lisa Strausfeld, a former partner at Pentagram and now at Bloomberg; Nicholas Negroponte, of MIT Media Lab and founder of One Laptop Per Child — to name but a few.

The work of Muriel Cooper, with its liberating effect on the graphic design medium, blurred the line between what the designer chooses to put on the page (or screen) and what technology can allow. An encounter the curators set up in this show captures the sensitivity of Cooper’s expansive method of working, and mirrors contemporary life’s fascination with remixing. For Cooper, it was more about process than product, investigation more than answers. The best characterization might be the designer’s own, quoted on the cover to the exhibition catalog: “There is still no magic way — but we propose to keep working at it. This stands as a sketch for the future.”

The exhibition closes tomorrow at the Arthur Ross Architecture Gallery in Columbia University’s Buell Hall before traveling to MIT Media Lab in Cambridge this September. A forthcoming book edited by Reinfurt and Wiesenberger will be published by MIT Press in 2016.

Observed

View all

Observed

Recent Posts

The New Era of Design Leadership with Tony Bynum Head in the boughs: ‘Designed Forests’ author Dan Handel on the interspecies influences that shape our thickety relationship with nature A Mastercard for Pigs? How Digital Infrastructure is Transforming Farming and Fighting Poverty DB|BD Season 12 Premiere: Designing for the Unknown – The Future of Cities is Climate Adaptive with Michael Eliason