November 15, 2018

My Pre-Holiday Dystopia Reading List

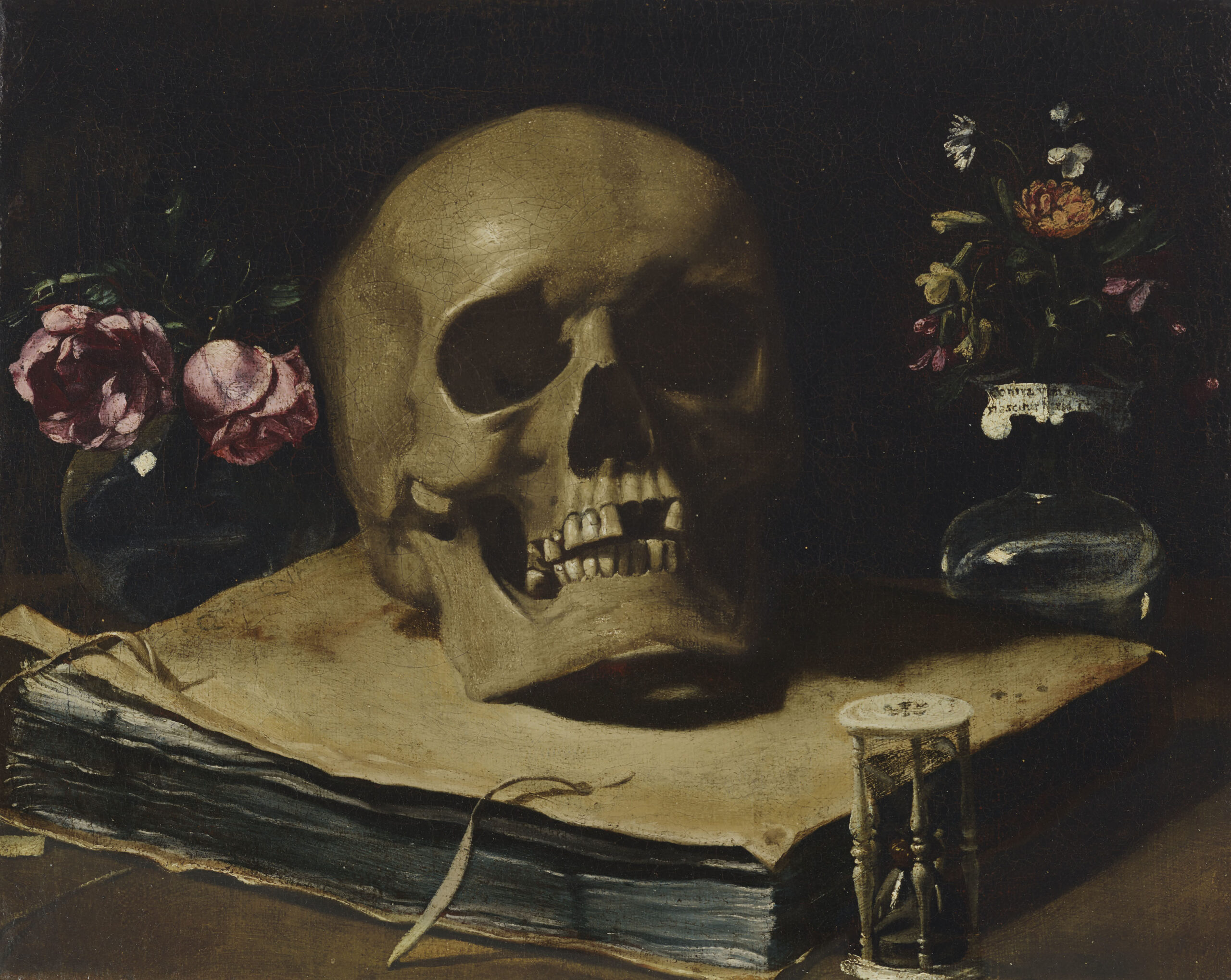

After the 2016 election my frustration and despair was mitigated by reading classic dystopia-lit. Fiction is an escape valve, so to speak — until it becomes reality. The following is my pre-holiday reading list for people, like me, who can cope with the high anxiety these books will trigger.

Now is a good opportunity to read Sinclair Lewis’s 1935 bestselling novel It Can’t Happen Here, in which a crafty demagogue, Democrat/populist Senator Berzelius “Buzz” Windrip takes the nomination away from the incumbent FDR at the party convention and goes on to beat his Republican challenger. Upon taking office Windrip outlaws dissent, jails political enemies in internment camps, and recruits a paramilitary group of thugs called the Minute Men, who violently enforce the policies of the new “corporatist” state. The “Corpo,” as it is called, curtails women’s and minority rights, and eliminates individual states by subdividing the country into administrative sectors. When “It Can’t Happen Here” was first published, America First, Christian Front and German Bund organizations were rapidly growing around the country (including New York City and Los Angeles), advocating revolution to “save the Constitution” from aliens, with many members of Congress supporting the cause. Despite the racist and nationalist rhetoric, this real threat to democracy did not happen here.

If you start reading now, you’ll be done by February.

Lewis’s ominous portrayal of fascism coming to America wrapped in the American flag was echoed in Philip Roth’s 2004 The Plot Against America, wherein aviation celebrity Col. Charles Lindbergh, a vocal supporter of Hitler, becomes the candidate of the America First Party, which opposes U.S. intervention in World War II and blames the “Jewish race” for trying to force war with Germany. Roth’s fictional story begins with a landslide upset win for Lindbergh against FDR. Lindbergh immediately signs a treaty with the Nazis and Japanese not to thwart their respective expansionist plans. The Plot was based on an actual movement of nationalist Republicans who unsuccessfully supported a Lindbergh run. It also draws on the vocal supporters in the U.S. for Hitler’s policies. Fortunately, the Plot never materialized – although it could just as easily have happened here if FDR was not in office.

Next, I read Thomas Rick’s 2017 Churchill and Orwell: The Fight for Freedom, which compares their biographical and philosophical similarities in the struggle to save England from the internal enemy — the “appeasers” who sought to make peace with Hitler. The resistance, valiantly led by Winston Churchill, was passionately supported by Orwell. The struggle to keep England afloat while fighting a persistent fifth column of English and American (notably, the American ambassador to England, Joseph P. Kennedy) appeasers is a scary page-turner. Had FDR not stuck to his guns, literally, the consequences would have been disastrous with the Nazis sitting on England’s doorstep.

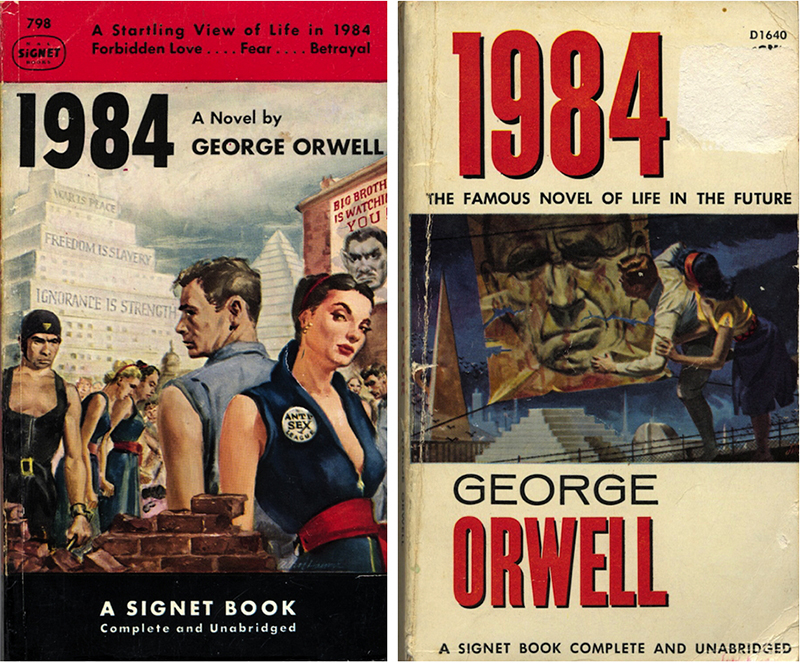

Orwell wrote propaganda for the BBC but was frustrated that he could not meaningfully help the war effort. Nonetheless, this period leads to his two most influential books, Animal Farm, a metaphor for communist autocracy, and 1984, a dystopian worldview and cautionary tale of what could happen if vigilance against demagoguery failed not just in totalitarian countries but in democracies too. 1984 addresses many of today’s concerns of truth versus untruth or alternative truth, language versus Newspeak and how, as Orwell wrote, “One does not establish a dictatorship in order to safeguard a revolution; one makes the revolution in order to establish a dictatorship. . . The object of power is power.”

1984 is mistakenly interpreted a metaphor for the absolute autocratic (in this case Stalinist) state. In fact, Orwell wrote it as a warning against a development which he believed would also take place in the Western-industrial countries, especially now. “The basic question which Orwell raises,” wrote Erich Fromm in the paperback afterword to 1984 “is whether there is any such thing as ‘truth.’ ‘Reality,’ so the ruling party holds, ‘is not external. Reality exists in the human mind and nowhere else . . . whatever the Party holds to be truth is truth.” Substitute the word “party” for “leader” and the consequence is the same. Truth is not an absolute any longer. And that is dangerous to liberal democracy – and freedom in general.

Fiction is an escape valve, so to speak — until it becomes reality.

After 1984 I read two other classic dystopias: Aldous Huxley’s 1931 Brave New World and Yevgeny Zamyatin’s 1921 We. Huxley’s book predicts a drug dependent/state controlled society. It takes place in the World State, in London in 2540, where citizens are artificially conceived in engineered wombs and controlled through an unforgiving childhood indoctrination program based on intelligence and labor. A process of sleep-learning maintains its citizens peaceful life and the happiness-producing drug called soma is a perpetual sedative. People live in glass apartment buildings and are carefully watched by the Bureau of Guardians.

We’s plot begins one thousand years after the novel’s so-called One State’s conquest of the entire world. The dystopian society depicted in We is presided over by the Benefactor and is surrounded by a giant Green Wall to separate the citizens from primitive untamed nature. All citizens are known as “numbers.” Every hour in a citizen’s life is directed by “The Table”.

We lead me back in time to Jack London’s 1908 The Iron Heel, generally considered to be “the earliest of the modern dystopian” fiction, it chronicles the rise of an oligarchic tyranny in the United States. The book is unusual among London’s writings in being a first-person of a woman protagonist written by a man. Much of the narrative is set in the Bay Area, including events in San Francisco and Sonoma County.

If you start reading now, you’ll be done by February. And if you have a tad more tolerance for dystopia don’t forget Ray Bradbury’s 1953 “Fahrenheit 451” and “Margaret Atwood’s 1985 “The Handmaid’s Tale.” You’ll at least feel a little better about living in the current version of “The Apprentice.”

Observed

View all

Observed

By Steven Heller

Related Posts

Design Impact

Ellen McGirt|Books

No mandates, only opportunities: IBM’s Phil Gilbert on rethinking change

Education

The Editors|Books

Your October reading list: The Design of Horror | The Horror of Design

Innovation

Vicki Tan|Books

How can I design at a time like this?

AI Observer

John Maeda|Books

Should we teach AI to reflect human values, emotions, and intentions?

Recent Posts

Raphael Tsavkko Garcia|Analysis

AI actress Tilly Norwood ignites Hollywood debate on automation vs. authenticity “I’d rather be a pig”: Amid fascism and a reckless AI arms race, Ghibli anti-war opus ‘Porco Rosso’ matters now more than everEllen McGirt|Holiday Gift Guide

Visions of sugar-plums ‘Adulterations Detected:’ on the human impulse to prettify our food with poisonRelated Posts

Design Impact

Ellen McGirt|Books

No mandates, only opportunities: IBM’s Phil Gilbert on rethinking change

Education

The Editors|Books

Your October reading list: The Design of Horror | The Horror of Design

Innovation

Vicki Tan|Books

How can I design at a time like this?

AI Observer

John Maeda|Books

Steven Heller is the co-chair (with Lita Talarico) of the School of Visual Arts MFA Design / Designer as Author + Entrepreneur program and the SVA Masters Workshop in Rome. He writes the Visuals column for the New York Times Book Review,

Steven Heller is the co-chair (with Lita Talarico) of the School of Visual Arts MFA Design / Designer as Author + Entrepreneur program and the SVA Masters Workshop in Rome. He writes the Visuals column for the New York Times Book Review,