November 23, 2010

New City Reader: Sidewalk Sale

“Color Mesh” by Mauricio Lopez. Photograph by Jesse Ross © 2010.

The seventh edition of the New City Reader, the New Museum’s bold/nutty experiment in broadsheet journalism as part of their exhibition The Last Newspaper, is hot off the presses. Titled “UnReal Estate” and edited by Mabel O. Wilson and Peter Tolkin, this edition tries to upend the domestic, postive, and lifestyle focus of the New York Times Real Estate section, by focusing on a few of the other possible meanings of the words. Here’s a Klaustoon included in the edition. Previous editions include “Sports,” featuring work by my colleague Mark Lamster.

If I had had all the time in the world, I might have imagined a Habitats column of the future. I took a stab at the fictional shelter form once before, in the fragment Wives of the Architects. But since I had three days, I focused on the increasing unreality of what may be Brooklyn’s current most famous piece of real estate: Atlantic Yards. Or Barclays Center. What are we calling it now?

“Sidewalk Sale,” originally published in the New City Reader 7, November 2010.

A few years ago, a friend of mine wrote a little ditty about Bruce Ratner and Jay-Z:

Buy one get one for free

If you need more just follow me

To the sidewalk sale, sidewalk sale

We got bottled dreams, failproof schemes

Lots of other stuff you don’t know you need

At the sidewalk sale, sidewalk sale

I was reminded of her song the other day, when I took the bus to Brooklyn’s Atlantic Center Mall, across the street from the hole in the ground that will one day be the Barclays Center. Groundbreaking for the project happened on March 11, 2010. So much organization, demonstration and emotion had gone in to preventing that day from happening; so much organization, calculation and presentation had gone in to making it happen. In the aftermath, what is there?

On my most recent visit the first thing I noticed was that the sidewalks had in fact been sold, in the sense that they had disappeared. Pedestrians can no longer walk along the south side of Atlantic Avenue, as that side of the street has disappeared behind jersey barriers and a construction vehicle lane that extends from Flatbush past Sixth Avenue. The short section of Fifth Avenue that used to connect Park Slope directly to the Atlantic Center Mall (without going all the way around the triangle at Atlantic and Flatbush) is gone, as is the Carlton Avenue bridge. The train cut, properly called the Vanderbilt Yard, was always a psychological moat. Now it is a physical one too.

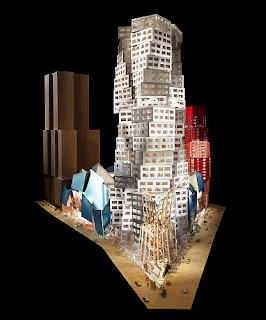

Model of “Building One,” Gehry Partners, 2008.

On the Flatbush side of the point, the sidewalk has simply been halved, creating a tight corridor between the onrush of traffic and the high construction fence, all the way to Dean Street. The first block of Pacific, as promised, has disappeared. You can barely hear the excavation over the traffic and can’t see it at all. If you loop around to Pacific on Dean, you find trash and sticklike trees, and a general sense of neglect. No one cares about this street anymore.

The loss of sidewalk is supplanted, though, by an even more significant disappearing act: Atlantic Yards, a name that located the project, has vanished as well. It was the brand for Frank Gehry’s design, and now the sponsor, the British financial services firm Barclays, is the headliner. Like Madison Square Garden, which hasn’t been on Madison since 1924, Barclays Center is a name designed for TV, for overhead blimp shots of the “helmet,” (which the new arena design clearly resembles). There’s nothing remotely Brooklyn about it; as of May, Russian Mikhail Prokhorov now owns 45 percent of the arena development, and 80 percent of the Barclays Center’s future tenants, the New Jersey Nets.

Rolling up the sidewalks and changing the name are the final steps of Phase 1 in the development process. Developer Forest City Ratner has succeeded in alienating these blocks of Brooklyn from the rest of the borough. From the beginning, the project’s press releases, and largely positive press coverage in the New York Times, played with the location and the condition of the railyards, calling them “Downtown Brooklyn” to naturalize the height of Gehry’s Miss Brooklyn tower, and invoking the threat of eminent domain to argue that they would be saving a blighted area.

Everything possible was done to ignore the real context, the adjacent neighborhoods of Fort Greene and Prospect Heights, which look better today than they did in 2003. Even now, when the buildings on Pacific and the north side of Dean have been reduced to dust (the block between Vanderbilt and Carlton looks like the photographs of selective demolition in Detroit), the charms of Prospect Heights are undiminished. Carlton Avenue offers an almost unbroken brownstone, tree-lined street front right up to the drop-off at Dean. The corner of Vanderbilt overlooking the yard has a newish restaurant, Cornelius (ha), with a façade reading “meat” “whisky” “oysters” and (I am sure) a side dish of retro facial hair. Up and down Dean new condominiums and renovated industrial buildings announce themselves with Neutraface numbers.

Rendering, SHoP Architects, 2010.

Across the street, it is a different story. Phase 2 has begun in what was once a neighborhood, and is now a non-place. There’s no way to cross from known world to known world without going all the way around the point, or further south on Atlantic Avenue. Ratner & Co. have succeeded in removing the railyard and adjacent blocks from our mental maps, for the interim, because there is nothing to see there.

The latest double-edged move is FCR’s participation in the city’s Urban Canvas program, which was organized by the NYC Departments of Buildings and Cultural Affairs and funded by the Rockefeller Foundation through the Mayor’s Fund to Advance New York City. The project wraps the Atlantic Avenue side of the site in a mesh screen designed by Mauricio Lopez. I love the Op-Art design, and Urban Canvas’s goal of beautifying construction sites, but it has double meaning deployed here. It is artsy, just like the original choice of Gehry, and has the latent suggestion that it is a gift to the neighborhood. But the graphic appeal shouldn’t distract us from the urban implications of a 228-foot, multi-year construction fence. In September, before Urban Canvas was installed, my brother, a professional photographer, was even asked not to take photographs of the site from the FCR-owned mall across the street. Now it seems like photos are OK, as long as they are of the art and not the work.

If you just moved to the area, the arena might sound like a good idea. Anything would be better than this. What was everyone fighting so hard to save? In the meantime, the rest of us hurry by on the little sidewalk we have left.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Alexandra Lange

Related Posts

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

The Observatory

Ellen McGirt|Books

Parable of the Redesigner

Arts + Culture

Jessica Helfand|Essays

Véronique Vienne : A Remembrance

Recent Posts

Mine the $3.1T gap: Workplace gender equity is a growth imperative in an era of uncertainty A new alphabet for a shared lived experience Love Letter to a Garden and 20 years of Design Matters with Debbie Millman ‘The conscience of this country’: How filmmakers are documenting resistance in the age of censorshipRelated Posts

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

The Observatory

Ellen McGirt|Books

Parable of the Redesigner

Arts + Culture

Jessica Helfand|Essays

Alexandra Lange is an architecture critic and author, and the 2025 Pulitzer Prize winner for Criticism, awarded for her work as a contributing writer for Bloomberg CityLab. She is currently the architecture critic for Curbed and has written extensively for Design Observer, Architect, New York Magazine, and The New York Times. Lange holds a PhD in 20th-century architecture history from New York University. Her writing often explores the intersection of architecture, urban planning, and design, with a focus on how the built environment shapes everyday life. She is also a recipient of the Steven Heller Prize for Cultural Commentary from AIGA, an honor she shares with Design Observer’s Editor-in-Chief,

Alexandra Lange is an architecture critic and author, and the 2025 Pulitzer Prize winner for Criticism, awarded for her work as a contributing writer for Bloomberg CityLab. She is currently the architecture critic for Curbed and has written extensively for Design Observer, Architect, New York Magazine, and The New York Times. Lange holds a PhD in 20th-century architecture history from New York University. Her writing often explores the intersection of architecture, urban planning, and design, with a focus on how the built environment shapes everyday life. She is also a recipient of the Steven Heller Prize for Cultural Commentary from AIGA, an honor she shares with Design Observer’s Editor-in-Chief,