Open the book, Hal

For better or worse, I have spent a lot of time in many design studios, and judging by the amount of memorabilia standing around, there is a deep relationship between science fiction and design. Probably this has much to do with the potent mix of progressive thinking and existential crisis inherent in both. I will go further and say that there is an unofficial canon of what I call “designers films,” most of which have a particular sci-fi bent and an evergreen popularity within the international creative community. This list naturally includes Star Wars but might extend to Moon, Solaris (both versions), Silent Running, The Andromeda Strain, Soylent Green (insert your favorites here) … and looming enigmatically above them all, Kubrick’s 1968 magnum opus.

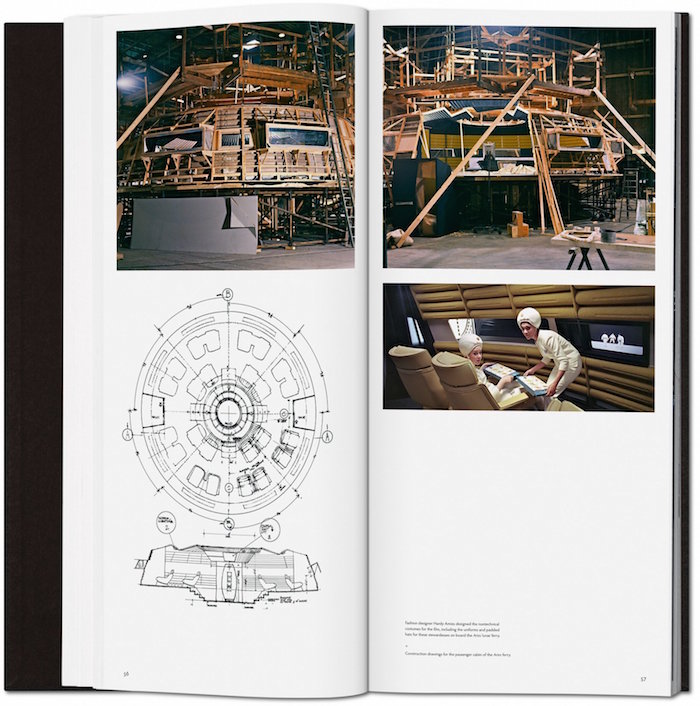

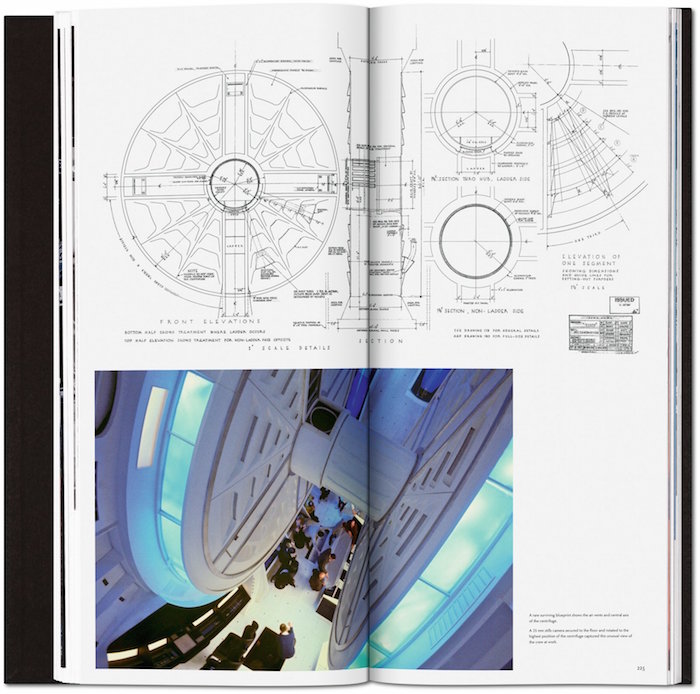

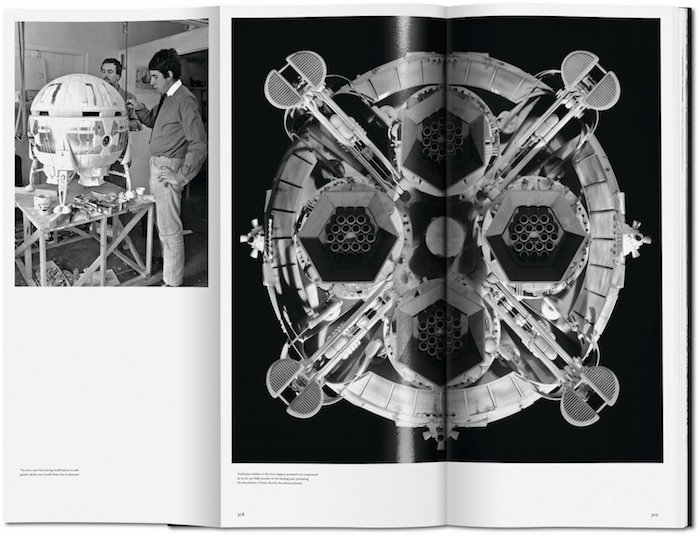

The result provides a real sense of the sheer scale of the production. Even those familiar with the film will be surprised just how thorough the creation of this version of the future was, more complete perhaps than any historical epic. It is a pleasure to discover how the production team, a heady mix of the best contemporary British film industry talent of the time, alongside an incredible set of experts drawn from the aeronautical and technological industries plus, of course, a certain Arthur C. Clarke, collaborated to create a highly realized mis-en-scene that looked “right” on every level, the perfect foundation on which to build an exploration of humanity’s development and consider what an extraterrestrial existence might mean for the future. If there is a criticism to be levelled it is simply that there is a suggestion that 2001 in its final form was inevitable—that somehow it emerged complete, rather than, as with any film production, experiencing many wrong turns along the way. That’s not to say that unused or jettisoned material is not represented, it is there in small ways, but often presented as an aside.

The book is therefore best understood as a personal invitation into the Stanley Kubrick Archive. It is not common knowledge, but housed within the University of the Arts London resides a vast resource of material related to Kubrick’s work. For many of his productions Kubrick produced an inordinate amount of research and development material. All of it was kept, although crucially, production elements themselves were always destroyed for fear of them being reused by rivals. What remains, therefore, is a vast resource of paperwork. Since the material was gifted to the college by the Kubrick family, it’s archivists have boldly taken on the epic task of cataloguing it. It must be said that what has ultimately been created is a big pile of boxes, albeit one that resides in a high-tech climatically controlled environment styled like the space Hilton itself.

It is therefore the job of passionate projects such as this book to corral the material into a cohesive narrative. As 2001 shows us, human beings are nothing if not fallible, and so perhaps inevitably there would have always been things that are missed. Having spent many hours personally researching within the archive myself I can reveal that there is plenty of interesting material that has not been presented here (I forgive the writer because he does mention my own favorite discovery—a spectacular misfire where a comic strip created for a hamburger franchise interpreted 2001 as a knockabout space adventure).

The Making of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey is pubished by Taschen and available here.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Jez Owen

Related Posts

AI Observer

Sigourney Schultz|Cinema

Dispirited Away: In the wrong hands, ‘Ghiblified’ genAI images erode ethos, empathy, and our very humanity

Arts + Culture

Susan Morris|Cinema

‘The conscience of this country’: How filmmakers are documenting resistance in the age of censorship

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Cinema

It’s Not Easy Bein’ Green: ‘Wicked’ spells for struggle and solidarity

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Cinema

About face: ‘A Different Man’ makeup artist Mike Marino on transforming pretty boys and surfacing dualities

Related Posts

AI Observer

Sigourney Schultz|Cinema

Dispirited Away: In the wrong hands, ‘Ghiblified’ genAI images erode ethos, empathy, and our very humanity

Arts + Culture

Susan Morris|Cinema

‘The conscience of this country’: How filmmakers are documenting resistance in the age of censorship

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Cinema

It’s Not Easy Bein’ Green: ‘Wicked’ spells for struggle and solidarity

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Cinema