Mark Ludwig|Books

December 31, 2009

Our Will to Live

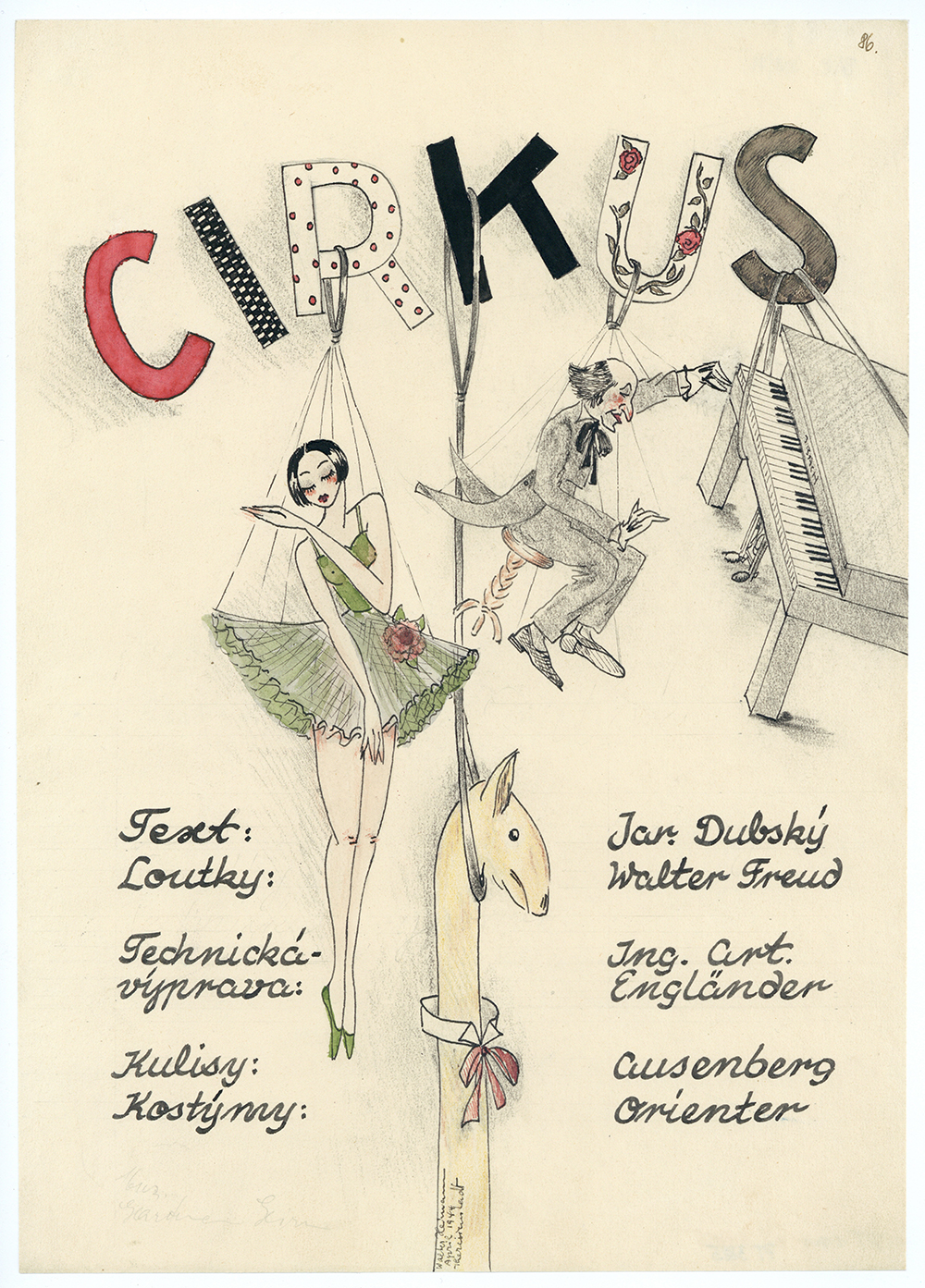

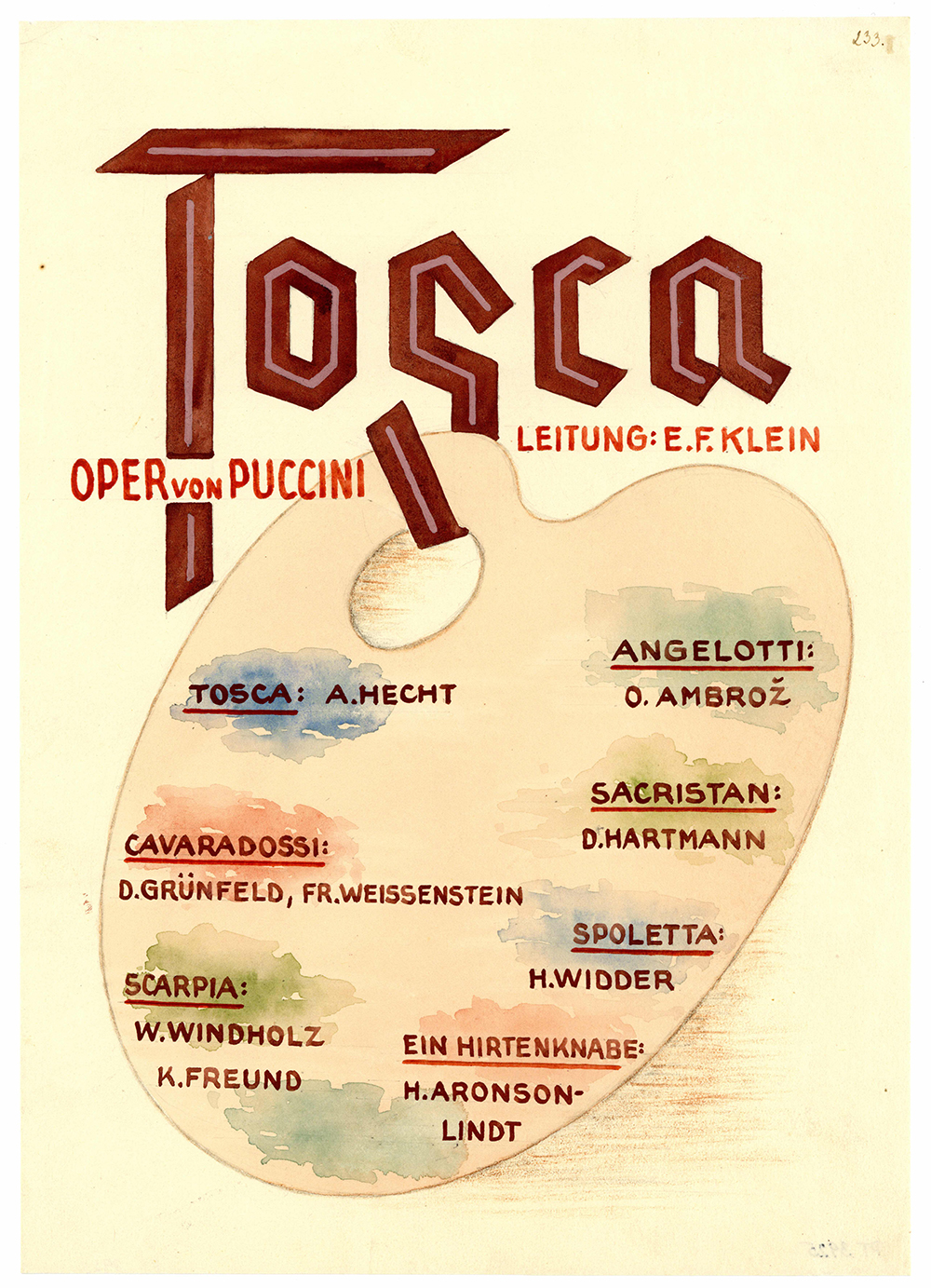

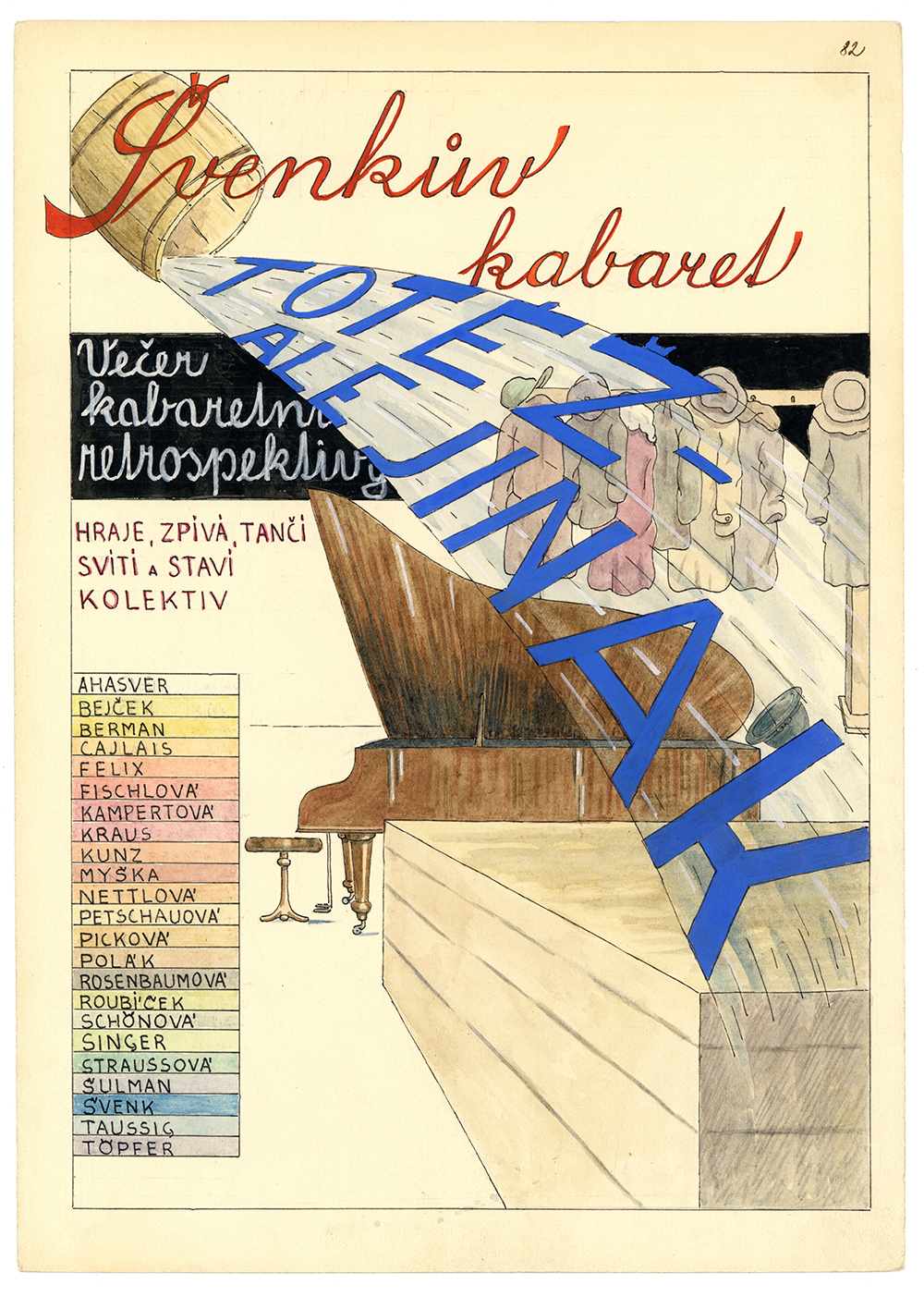

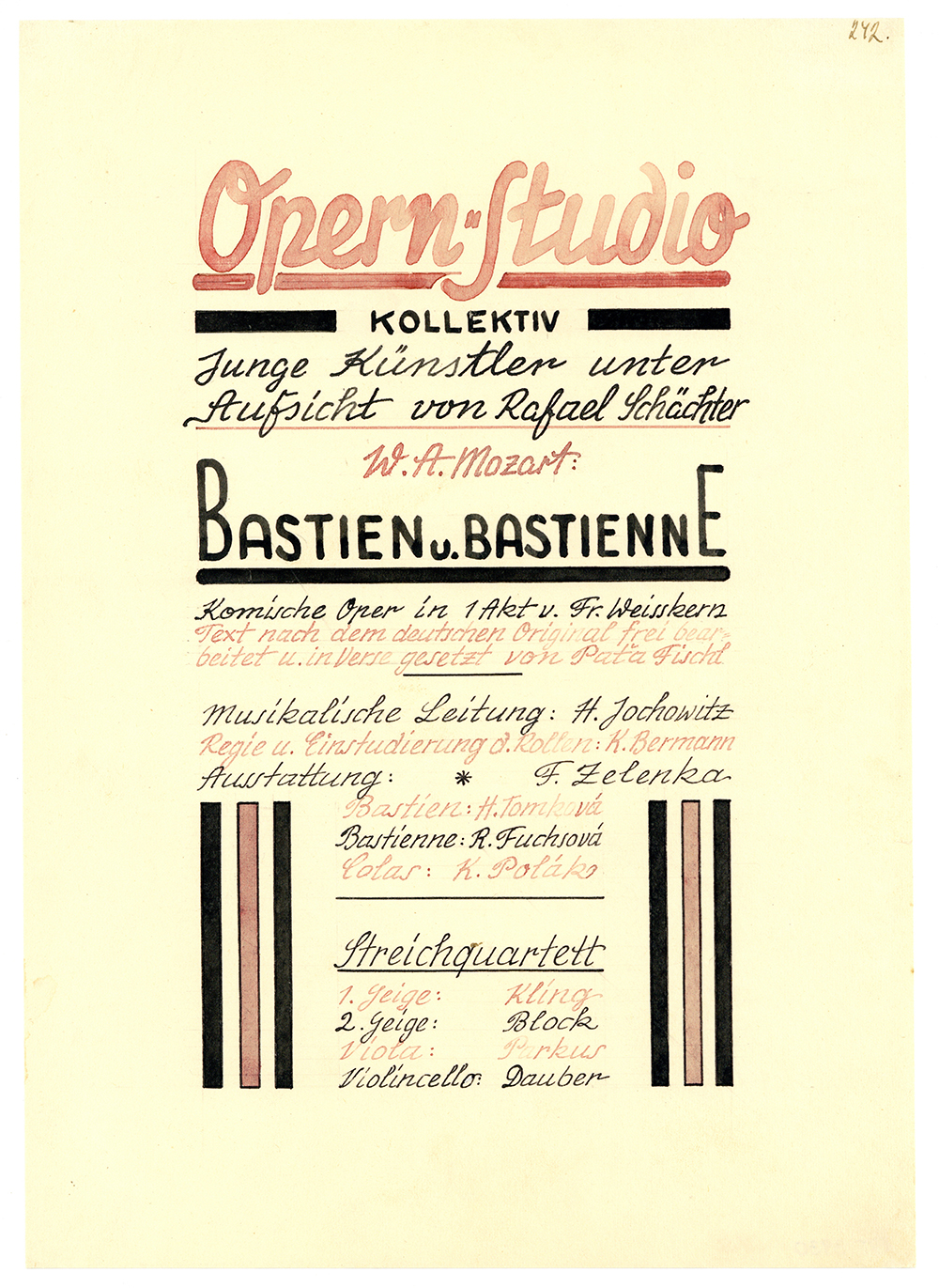

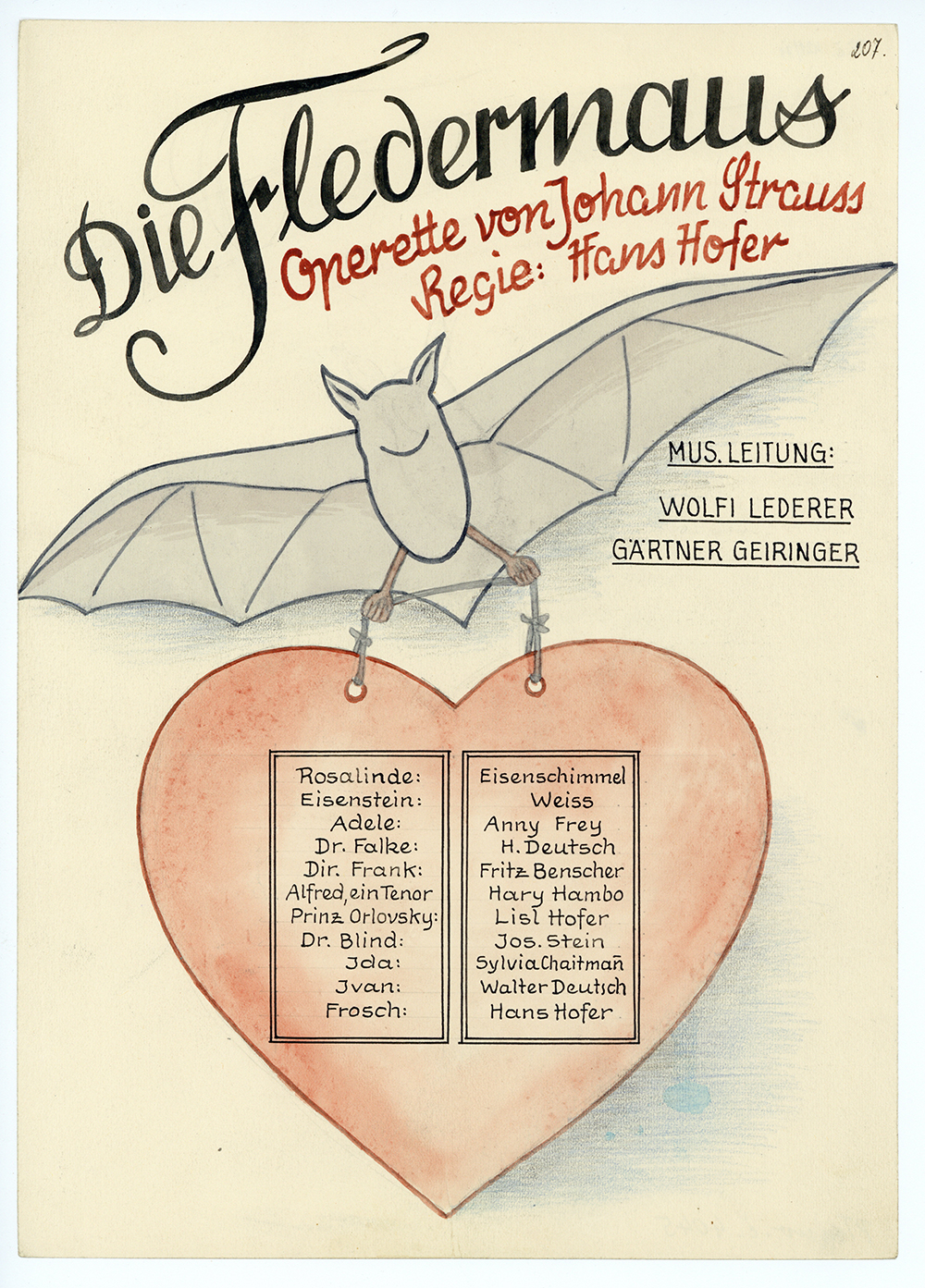

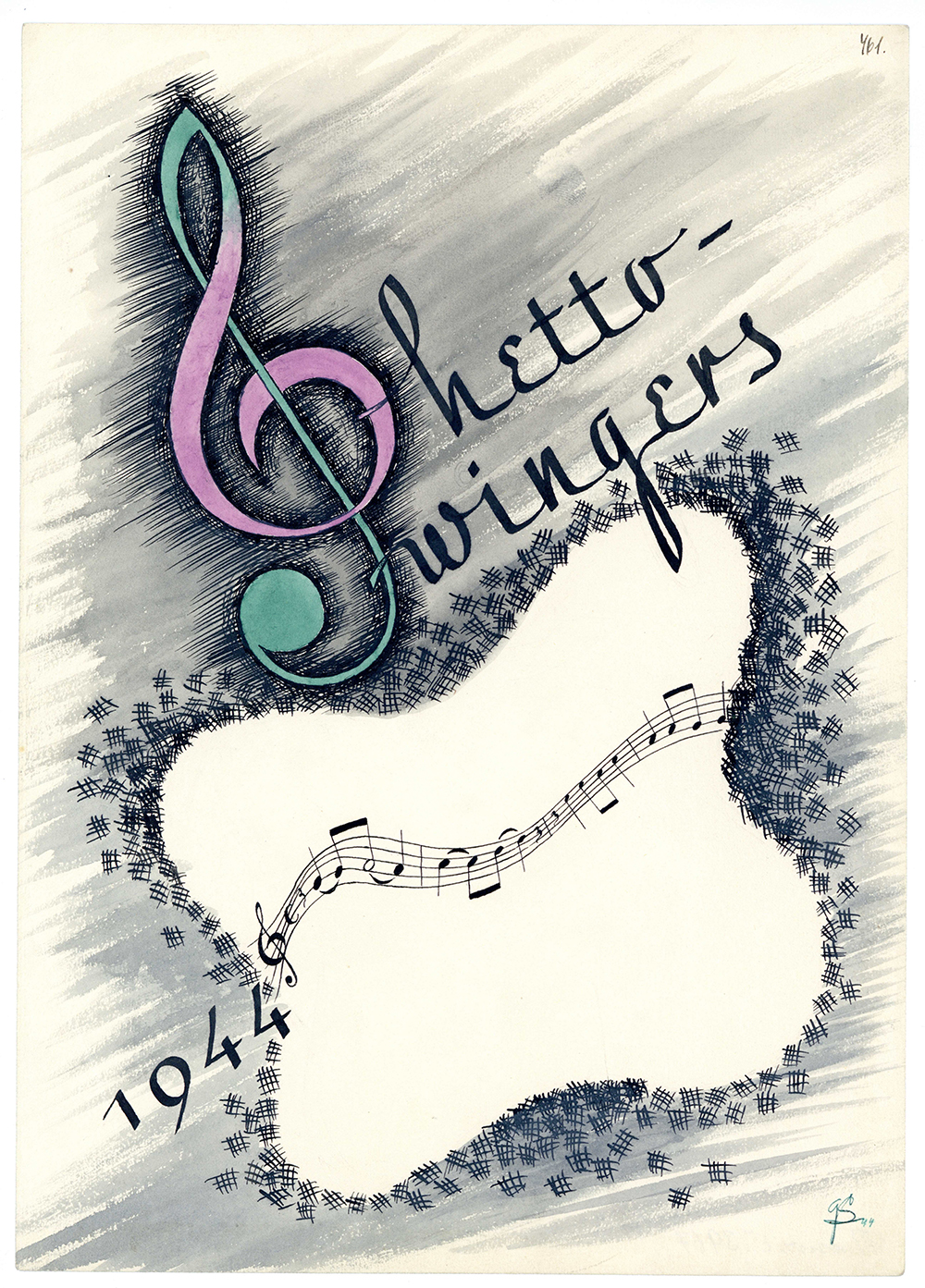

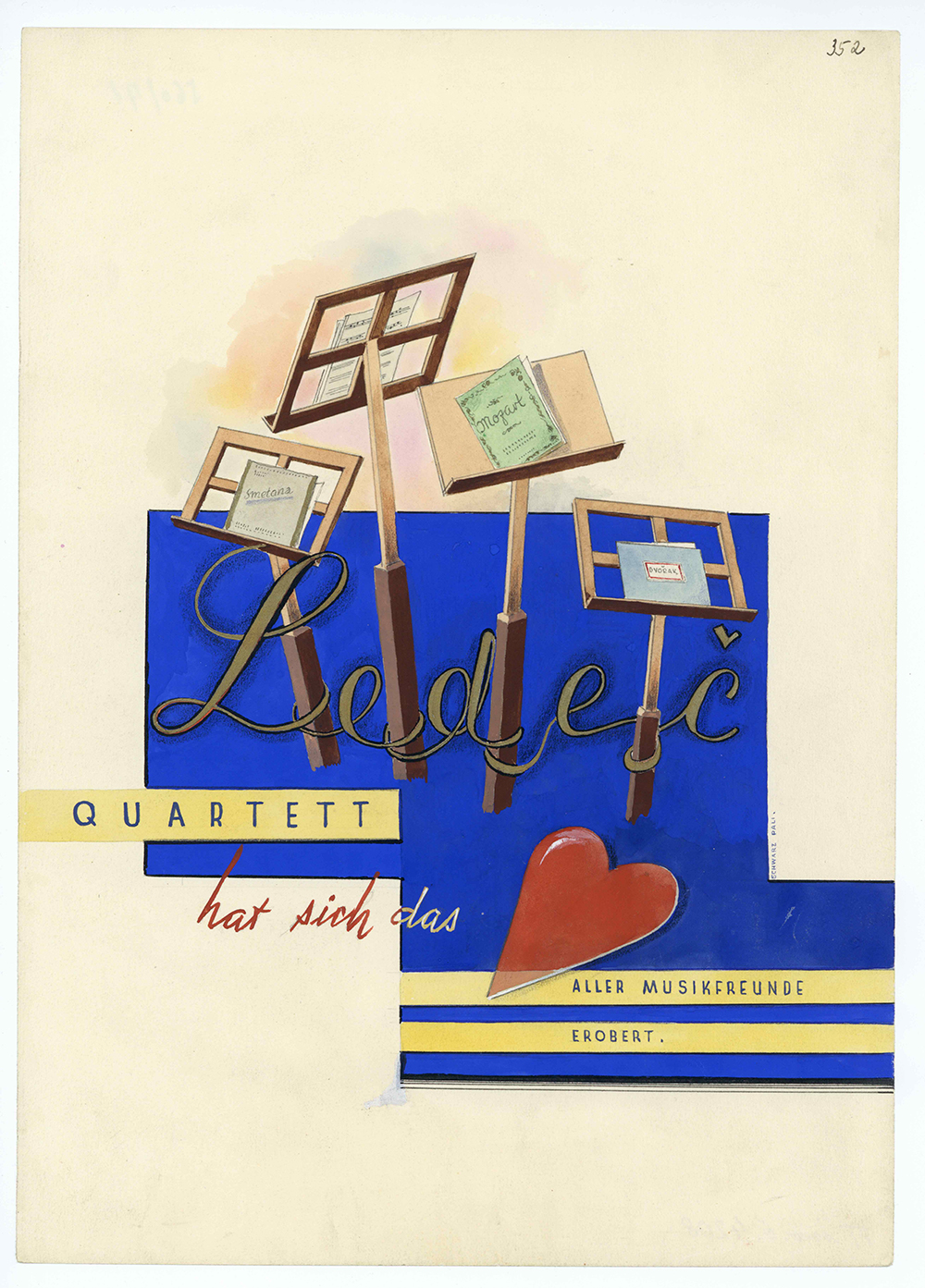

Editor’s Note: The following text and images are reprinted from Our Will to Live, a new book out from Steidl by Mark Ludwig. It presents the first full translation of Terezín prison camp concert critiques written by accomplished musician, scholar—and Terezín prisoner—Viktor Ullmann. Paired with Ullmann’s critiques are more than 250 rarely seen concert posters, programs, portraits and scenes rendered by imprisoned artists; these are from a trove of hidden artworks recovered after liberation.

You may be familiar with I Never Saw Another Butterfly, the famous collection of touching poems and drawings child prisoners created in the Terezín concentration camp. But most people are startled to learn of a rich repertoire of music performed and composed in Terezín. A little more than thirty years ago, I had the same response.

My curiosity led me to reach out to the ÄŒeský Hudební Fond (Czech Music Fund) in Prague, the central resource in Czechoslovakia for music by Czech composers, and to make my first visit to that historic city. At the time, the Fund’s office was located on PaÅ™ížská Street, a beautiful boulevard lined with Art Nouveau buildings in what is known as both Staré MÄ›sto (Old Town) and the Jewish Quarter, only paces from the famed Alte-Neue Schule and the Old Jewish Cemetery. On that first visit, I had three profound experiences that changed my life.

Hearing the stories of these imprisoned artists, viewing their little-known musical scores, and learning the history of Terezín amounted to one of the most emotionally and intellectually overwhelming experiences of my life—as an artist, a Jew, and a human being. It launched a thirty-year journey devoted to researching, performing, recording, writing, and teaching about the Terezín composers and artists. In 1990, I founded the nonprofit Terezín Music Foundation to support this work.

Our Will to Live is part of this effort. Through text, visual art, and recordings, it journeys into Terezín’s active cultural community. At its core are twenty-six concert programs given in Terezín, described in richly literary and learned critiques by composer Viktor Ullmann, along with stunning artwork created to promote and document these musical events and their artists. With his critiques, Ullmann chronicles much of the significant cultural life in the camp. Each critique is accompanied by a selection of color images showing the hand-drawn, painted, and hand-lettered concert posters, programs, sketches, and other works secretly collected in the camp by a member of the Jewish leadership.

The history and art of Terezín transcends cultural and generational boundaries. One of my most memorable experiences was performing this repertoire with students and faculty of the Sarajevo Music Academy after the lifting of the horrific siege in the 1990s. We performed in the Academy’s concert hall, where the bombardment had left a gaping hole in the wall.9 The stories and music of Terezín resonated deeply with our audience, who had lost family and friends and braved sniper fire to attend lessons, rehearsals, and concerts. The arts helped sustain them through tremendous brutality. More recently, we have endured separation and loss during the Covid-19 pandemic. People sang from balcony windows. Instrumentalists and singers—professional and amateur—produced in-home concerts shared via the internet. And eighty-nine year-old Holocaust survivor Simon Gronowski moved his electric keyboard to his window and played jazz tunes to lift the spirits of his neighbors. Many inspiring acts reaffirmed the arts as a vital source of solace, connection, and hope. Surely, Terezín’s story reaches across time and place in its power to inspire exchange and dialogue and remind us of our shared humanity.

In October of 1944, Viktor Ullmann and Karel Heřman received notices for transport from the Theresienstadt1 concentration camp to Auschwitz. Both men made fateful decisions to leave their most valued possessions behind.

Ullmann, one of the most respected and gifted composers of his generation, entrusted his musical scores and personal writings—including a series of twenty-six detailed and learned critiques of musical performances in the camp along with two short, yet touching and inspiring personal reflections—to a friend and fellow prisoner. HeÅ™man, a member of the Terezín Jewish administrative leadership, had collected hundreds of documents and works of art created by fellow prisoners. He hid them during the closing weeks of his incarceration in Terezín.

HeÅ™man’s trove miraculously survived and today offers a vibrant testament to the artistic determination and courage of the Terezín prisoners. It includes more than five hundred items—posters, programs, portraits, tickets, and administrative forms—documenting many of the cultural activities in the camp.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Mark Ludwig

Related Posts

Books

Jennifer White-Johnson|Books

Amplifying Accessibility and Abolishing Ableism: Designing to Embolden Black Disability Visual Culture

Books

Adrian Shaughnessy|Books

What is Post-Branding: The Never Ending Race

Arts + Culture

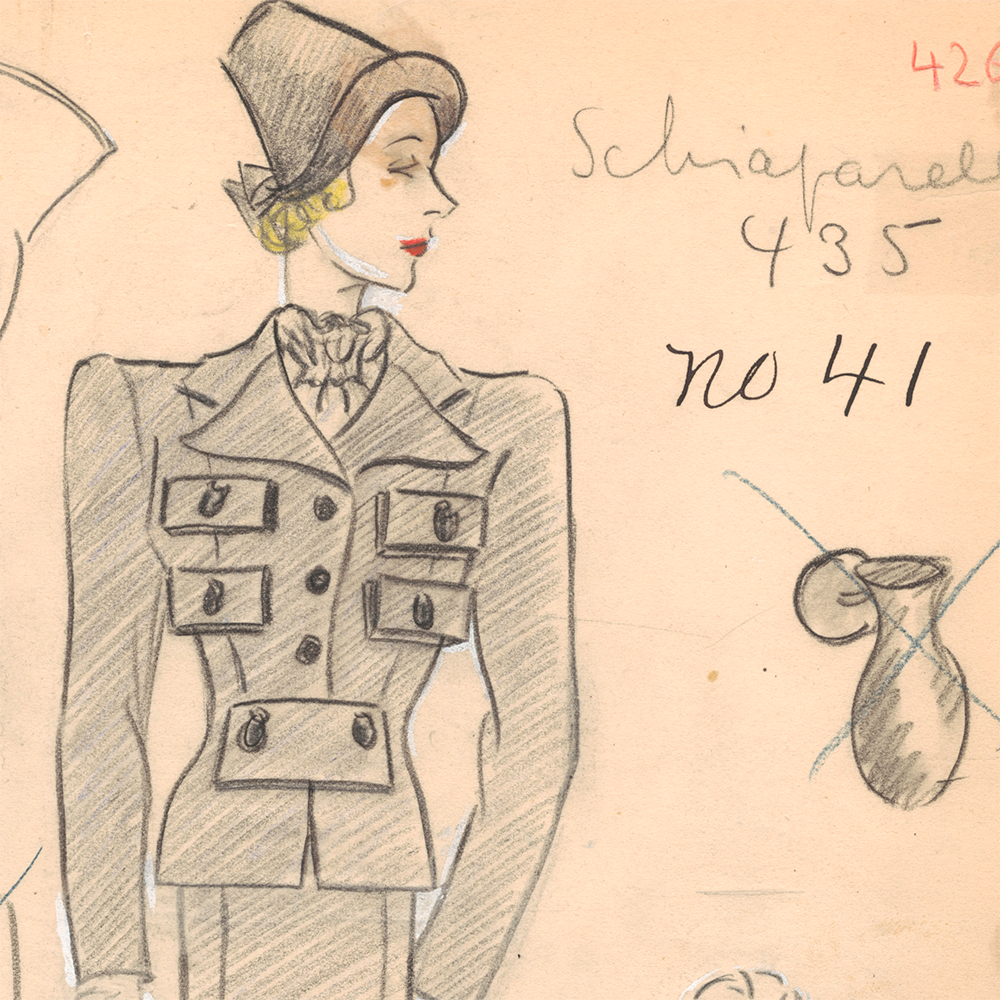

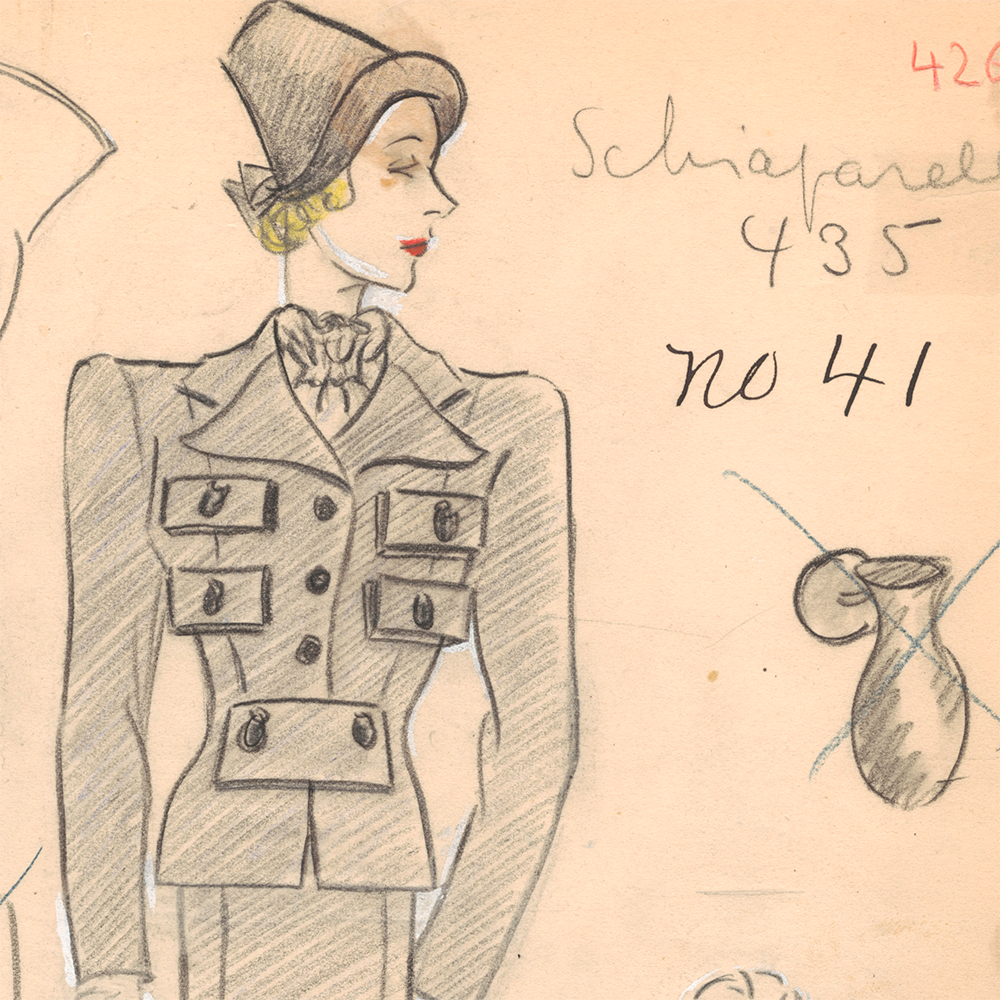

Hannah Carlson|Books

Schiaparelli’s Pockets

Books

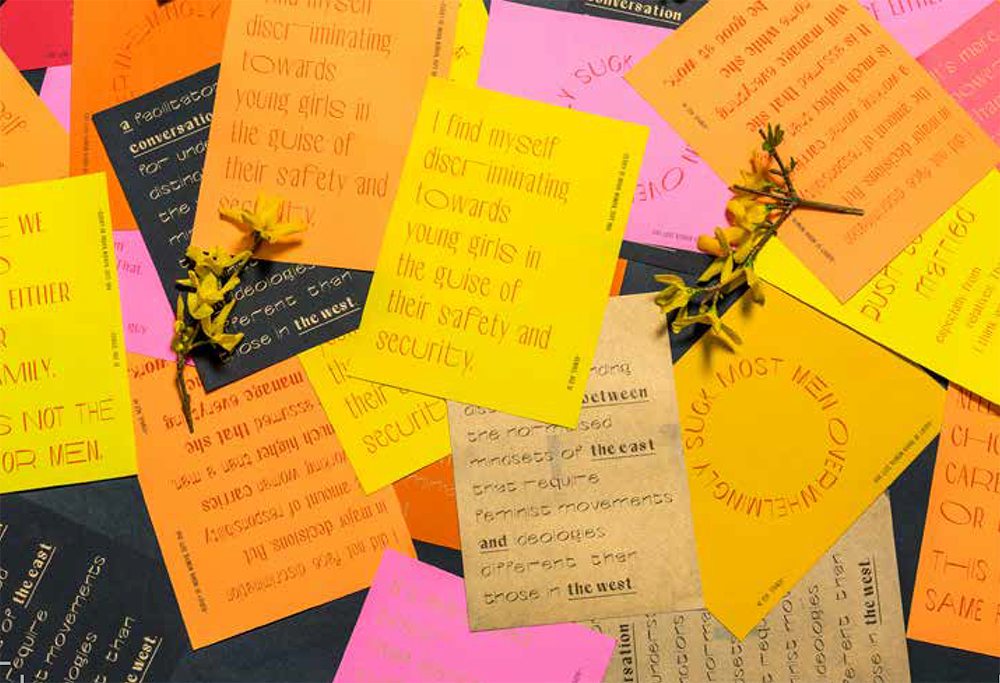

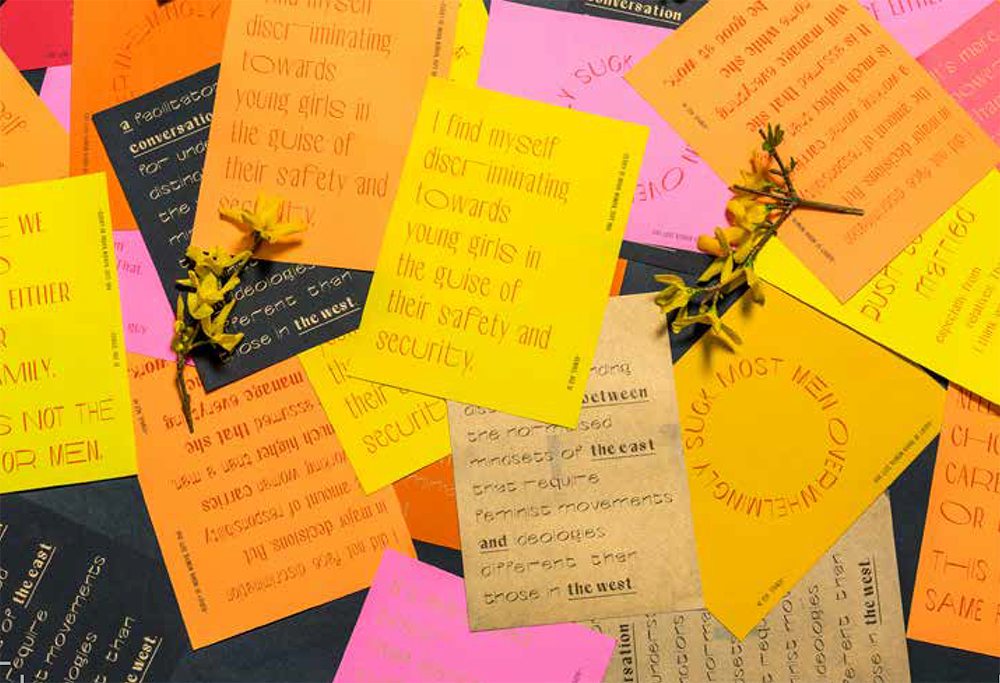

Alison Place|Books

On Fighting the Typatriarchy

Recent Posts

‘The creativity just blooms’: “Sing Sing” production designer Ruta Kiskyte on making art with formerly incarcerated cast in a decommissioned prison ‘The American public needs us now more than ever’: Government designers steel for regime change Gratitude? HARD PASSL’Oreal Thompson Payton|Interviews

Cheryl Durst on design, diversity, and defining her own pathRelated Posts

Books

Jennifer White-Johnson|Books

Amplifying Accessibility and Abolishing Ableism: Designing to Embolden Black Disability Visual Culture

Books

Adrian Shaughnessy|Books

What is Post-Branding: The Never Ending Race

Arts + Culture

Hannah Carlson|Books

Schiaparelli’s Pockets

Books

Alison Place|Books