On the eve of the publication of Patternalia: An Unconventional History of Polka Dots, Stripes, Plaid, Camouflage & Other Graphic Patterns, author Jude Stewart elaborates on some of her favorite topics from the book.

++++

Archive-plundering, like many forms of creative work, can feel like a desert trek. There you are again, tongue lolling dryly out, your parched eyelids glued to the back-lit screen as you scroll and scroll. Desperate for one juicy drop of What You’re Actually Looking For. If, like me, you persist in researching topics at a perverse slant to how libraries like to organize their knowledge, the slog can be long. What keeps you hooked, though, are the unexpected flash-floods—those scintillating moments where the perfect book, the one you’d never dream to search for directly, drops into your palm. Pattern Poetry: Guide to an Unknown Literature (1987) by Fluxus poet Dick Higgins was that kind of dew-beaded glass of cool water. Actually, call it a double-oasis: the book itself was an extraordinary find for my project, but its author was that inestimable comfort in the lonely, quixotic business of creative work: a fellow seeker.

My forthcoming book Patternalia: An Unconventional History of Polka Dots, Stripes, Plaid, Camouflage & Other Graphic Patterns began as an outlandish thought experiment. What if you could pop not a keyword into Google search, but a wordless image—say, a snippet of pink-and-white polka dots? What farflung cousins to this visual might you locate in different cultures, disciplines, and contexts, traveling under different names and each suggesting different meanings? How many unexpected stories could intersect behind a simple visual? To pile absurdity onto absurdity, this totally undoable experiment struck me as the right way to investigate a curious parallel phenomenon: Why, at a gut level, do we imbue patterns with personalities? Why should polka dots seem demure, stripes speedy and decisive, or gingham wholesome? The answers, of course, lie in the layered, often conflicting meanings and associations each pattern accrues over time.

Pattern Poetry takes on a herculean task that consumed twenty years of Higgins’ life: to mine world literature for pre-1900 examples of poems whose visual appearance on the page matters to its sense—pattern writ visible, literally. His book calls its subject “pattern poetry” to differentiate pre-1900 works for more modern incarnations and terms. Brazilian poet Augusto da Campo’s early manifesto for concrete poetry articulates many of the aims of all pattern poetry: in every form it “refuses to absorb words as mere indifferent vehicles, without life, without personality, without history—taboo-tombs in which convention insists on burying the idea.” Typographers, behold your tribe! All graphic designers will recognize that peculiar, even irrational satisfaction: of nudging a word infinitesimally into the “right” place on an empty canvas.

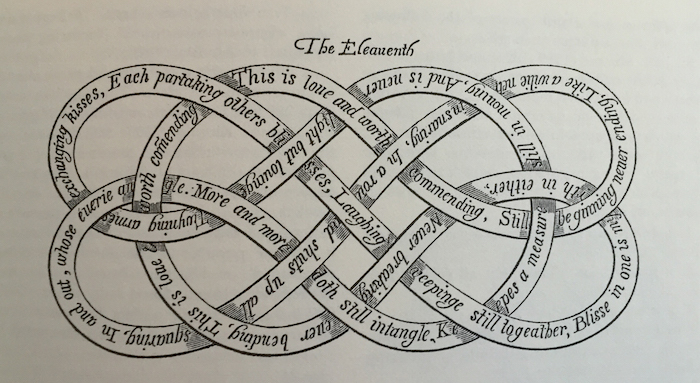

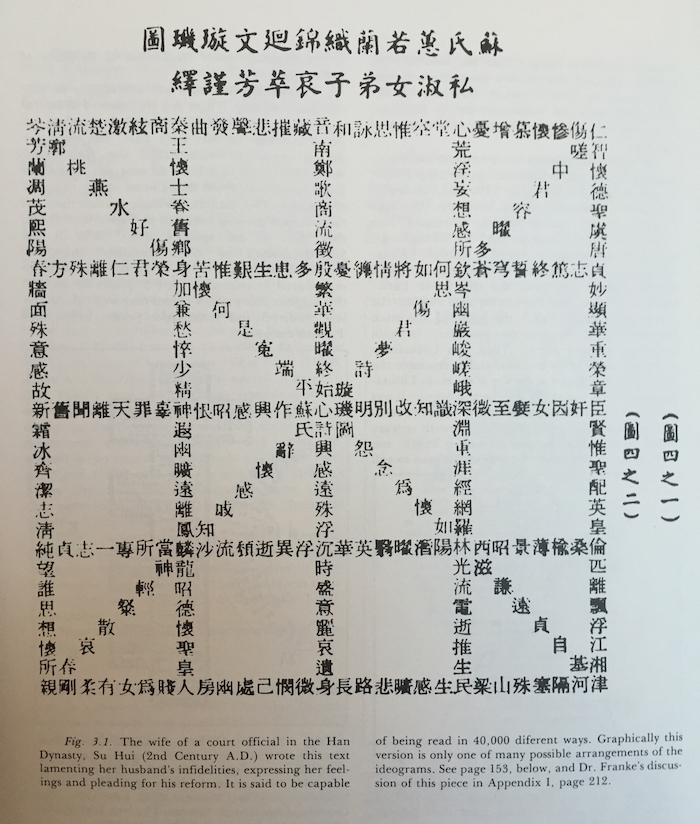

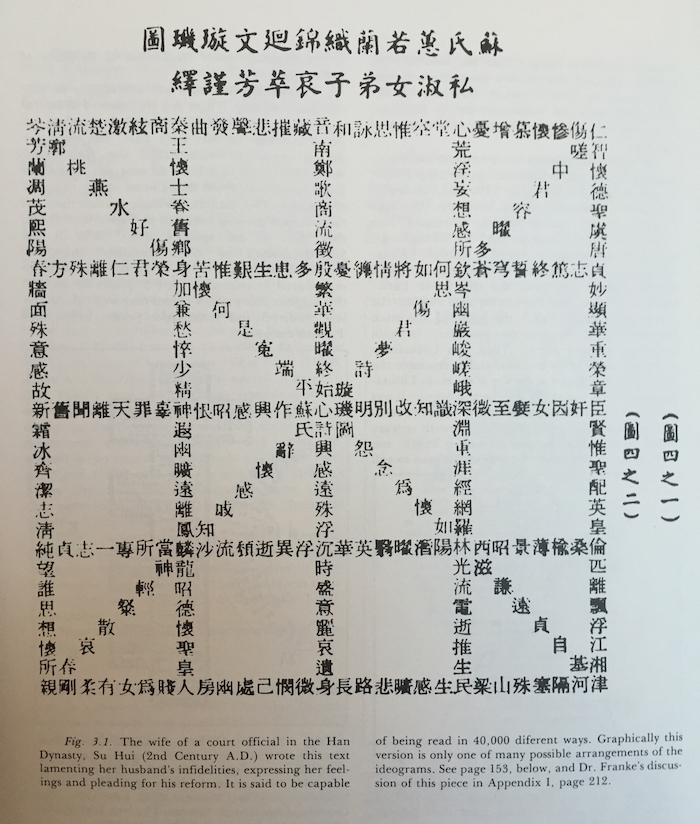

So many interesting tendrils—and tensions—spill out from Higgins’ pages. First and foremost is the tension between word and image and the infinite variety of games one can fashion, cat’s-cradle-like, by stringing those two elements together. A quick perusal of Pattern Poetry’s pages spins you past love-knot poems (endless knots of text whose lines can be read in any order); language-mazes; acrostic-gravestones. Indian citrakÄvyas are poems shaped like wheels, lotuses, swords, necklaces, or “the path of falling urination of a cow.” One famous Chinese hui-wen (a kind of endless-knot poem) written in the 2nd century B.C.E. can be read 40,000 different ways.

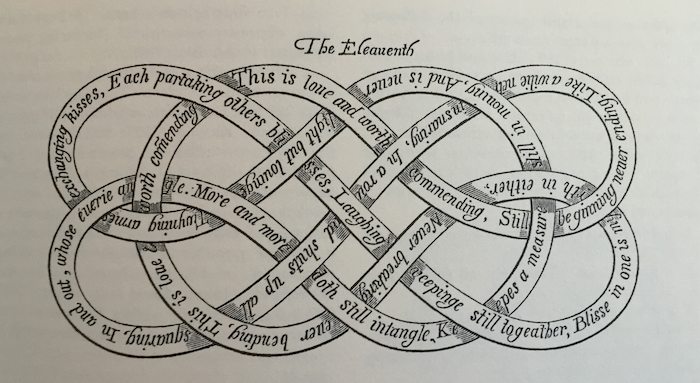

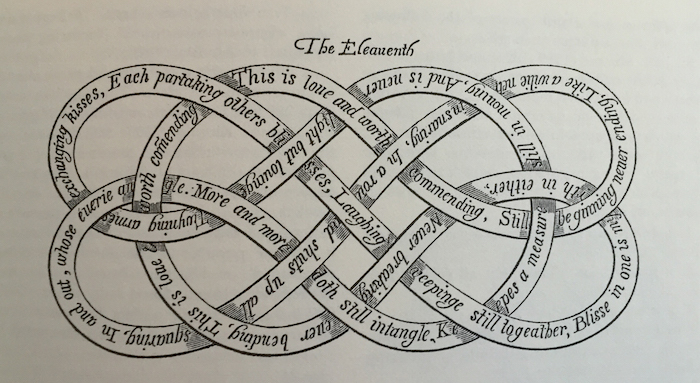

According to Pattern Poetry, this is the earliest known “lover’s knot” in English, from Britannia’s pastorales by William Browne (1613–14)

According to Pattern Poetry, this is the earliest known “lover’s knot” in English, from Britannia’s pastorales by William Browne (1613–14) This famous hui-wen from the 2nd century B.C.E. can be read in 40,000 different ways

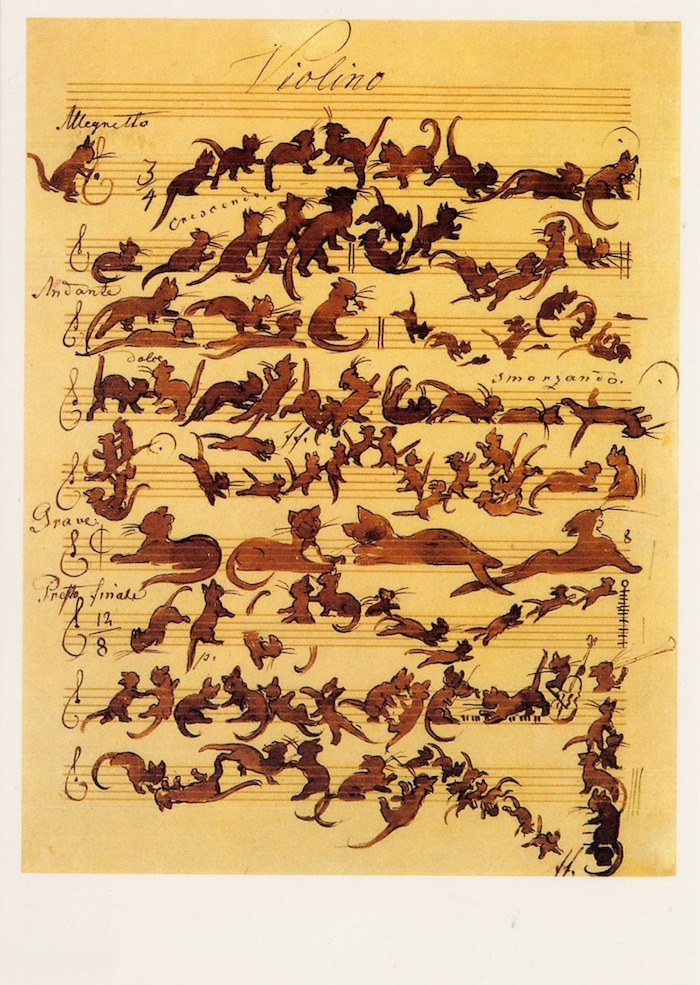

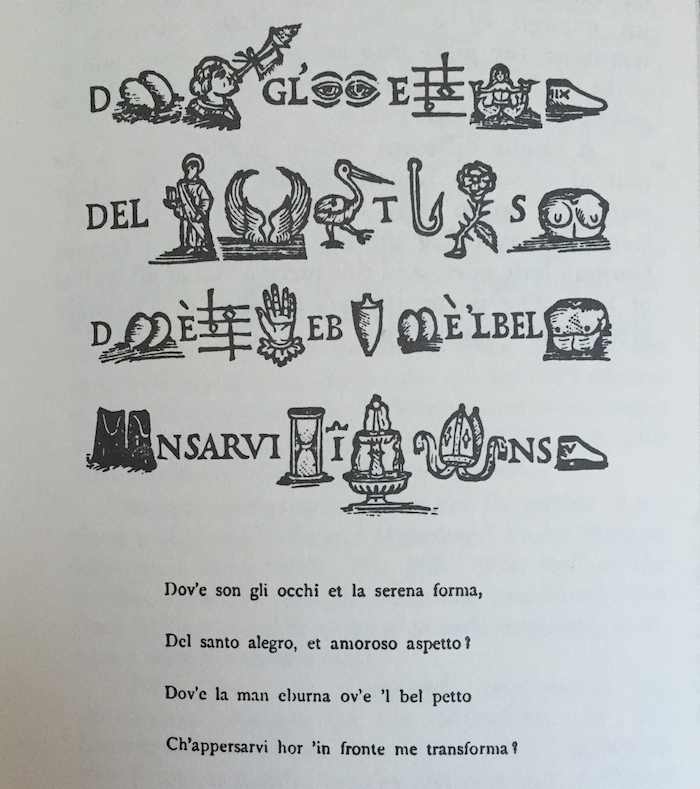

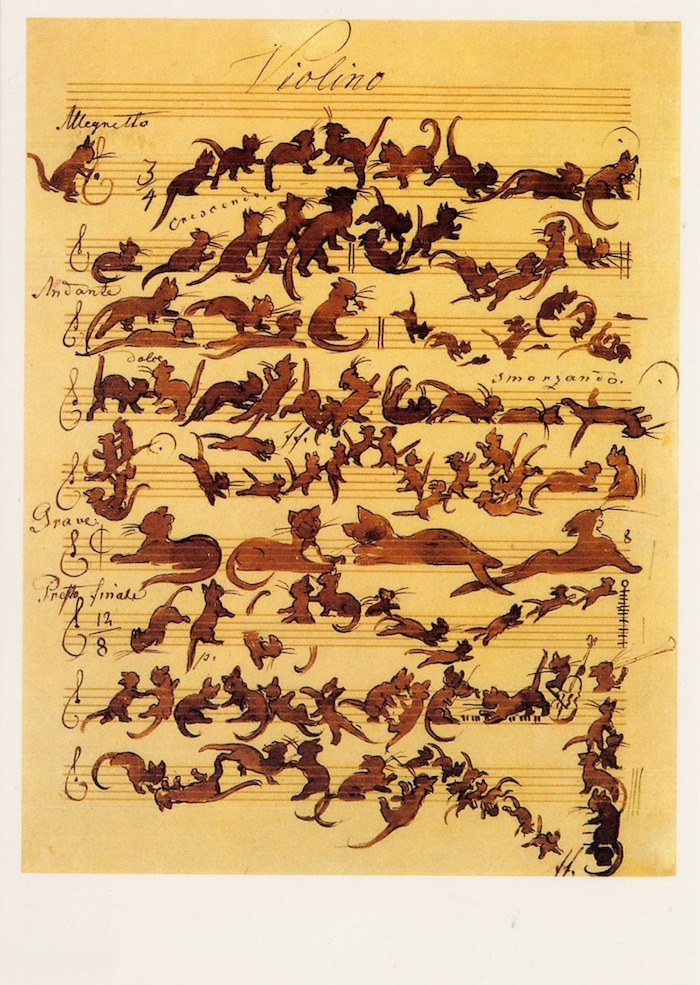

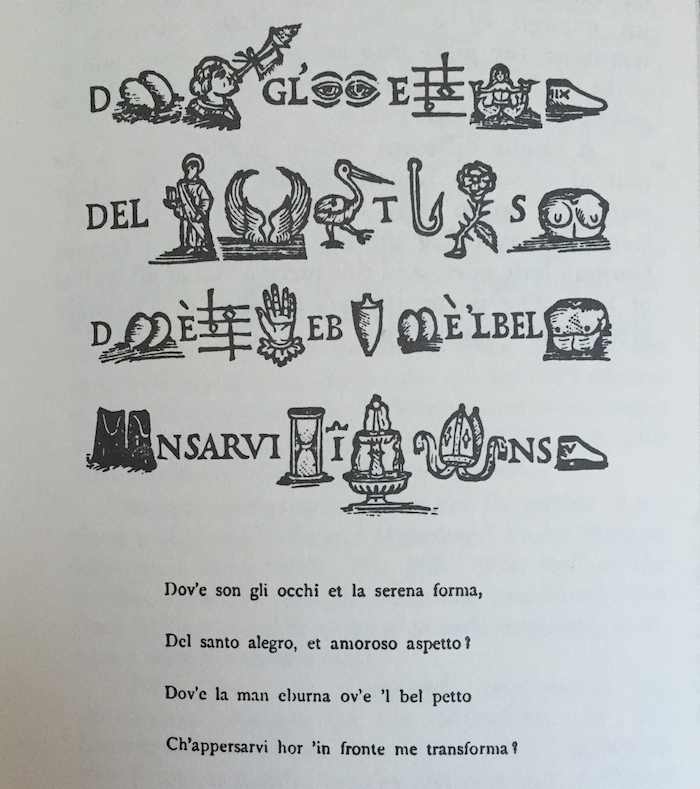

This famous hui-wen from the 2nd century B.C.E. can be read in 40,000 different waysThis topic begs to proliferate, and—kudzu-like—Higgins both coaxes and and marvels at his own sprawl. The entire fourth chapter of his book is devoted to “Analogous Forms”: rebuses (a hybrid words-and-text poem, full of punning images); Japanese ashide-e (calligraphic pictures, in which the poet’s body is pictured, fashioned from his own text); and musical notation unusually visualized like Hadyn’s bullseye-shaped score “Das erste Gebot” (actually playable) or “Die Katzensymphonie,” by Moritz von Schwind, musical staff paper romping with black-silhouette cats (not at all playable).

Page from the nonsense musical score “Die Katzensymphonie” by Moritz von Schwind, 1868

Page from the nonsense musical score “Die Katzensymphonie” by Moritz von Schwind, 1868 A sixteenth-century Italian rebus and its solution

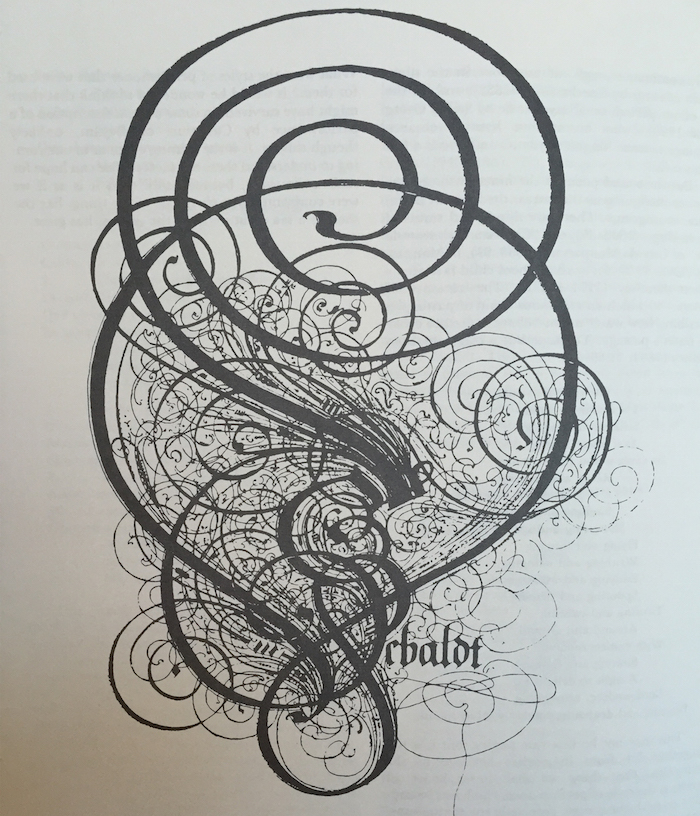

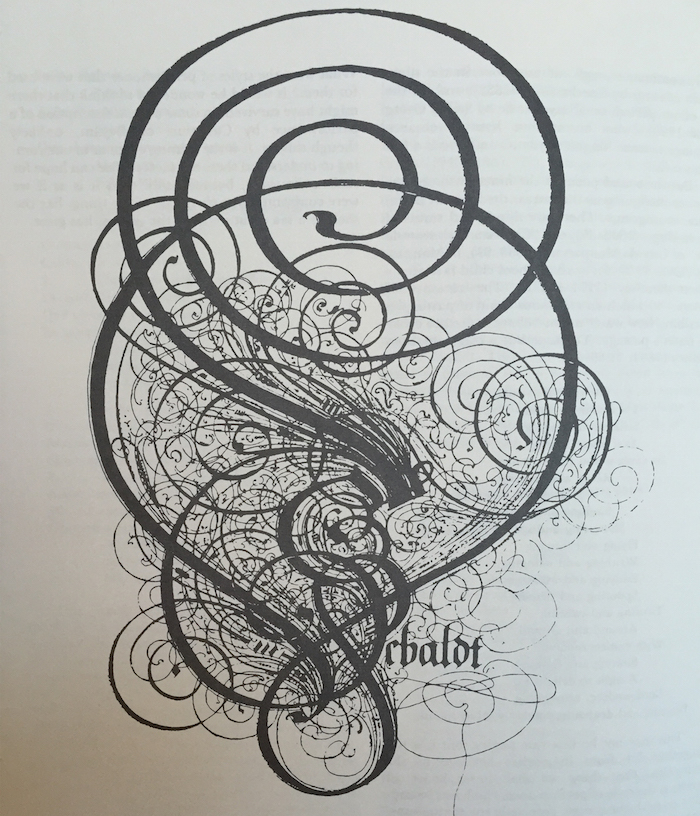

A sixteenth-century Italian rebus and its solution A cousin of pattern poetry, this calligraphic labyrinth dates from a 1589 genealogy book

A cousin of pattern poetry, this calligraphic labyrinth dates from a 1589 genealogy bookBut the second fascinating tension of the book is between brain and heart. You get the sense of a tenacious labor of love, in which scholarly rigor is a means of mastering a private, wildly voracious devotion. Or maybe this tension is better described as that between a creative idea and its execution. Fluxus artists like Higgins loved this marriage of ridiculousness and fidelity, of conceiving a wild-eyed idea in a flash and then committing to the slow, extraordinary grind required to realize it. Who knew that the composer of the Danger Music series—in which performers are variously instructed to scream their throats raw, “volunteer to have your spine removed,” or play scores whose notes are the bulletholes made by machine-gun fire—could also write 12,000+ letters to literary scholars to amass these poems? Higgins footnotes like the dickens and betrays throughout the book’s text not a whiff of his personal enthusiasm for the subject. And yet, the book’s existence, complete with an intimidating bibliography, speaks loudly enough. If comedy equals tragedy plus time, creative work might equal absurdity plus doggedness, with time as its proxy.

Patternalia Klee quote, from Patternalia: An Unconventional History of Polka Dots, Stripes, Plaid, Camouflage &

Patternalia Klee quote, from Patternalia: An Unconventional History of Polka Dots, Stripes, Plaid, Camouflage &

Other Graphic Patterns, illustration by Oliver MundayWhy make pattern poetry at all? Why insist on text’s visual presence? Higgins avoids the question, and yet the question asserts itself over and over as you turn his book’s pages. In some cases, visualizing a text is a creative workaround: Hebrew micrography are texts pulled from biblical law and shaped into gryphons, dragons, or geometrical webs, thus neatly sidestepping Orthodox Judaism’s ban on imagery. Arabic kufic inscriptions, in which script is distorted to fill a shape, operate on a similar principle. In many other cases, the visualization introduces a creative limit or asymptote the author must write around.

To me, to Dick Higgins, and to all designers, though, how text looks on a page is always inseparable from its larger meaning. To elide over this fact needlessly narrows down one’s perceptions of the world. White space isn’t empty so much as suggestive. Caesura, visual or textual, punctuate ideas, shape their pacing, and give them resonance. Pattern poetry enlarges your senses, literally, marrying sound, sense and image in an exciting singularity. As I tried to do in Patternalia, it trains an unexpected new lens on an ignored corner of the world: whether the global depth and breadth of “trivia” poems, or the surprising, untold histories of the patterns pervading your sock drawer.

Jude Stewart writes about design and culture for Slate, The Believer, Fast Company and Print among others. Her first book,

Jude Stewart writes about design and culture for Slate, The Believer, Fast Company and Print among others. Her first book,