November 27, 2013

Saul Leiter: Remembered

Saul Leiter and the author’s daughter.

After writing the following for the Design Observer in 2009, I became a friend of Saul Leiter’s. More than a friend: Saul became a mentor, a confidant, almost a father figure to me. Twice a month, for going on three years, I would visit with him in his east village apartment, usually in the afternoons. We would sit and talk for hours, often ending with a late dinner of peroigi and borscht at a nearby restaurant.

While we talked, Saul would often pause, bend from his chair, and pick up a battered portfolio from one of the piles that were usually stacked by his feet. He would haul the portfolio onto his lap and flick through its contents. Inside there would be photographs, paintings and his painted photographs, usually all jumbled together. He would pause in mid-sentence, pull one out and say, “that’s quite nice” with astonishment, as if he had never seen his own work before. His life, and its accomplishments, were a continual source of wonder and surprise for him. “I don’t understand how I did what I did” he would say.

But he did what he did, and what he did, primarily as a photographer but also as a painter, is significant. It was also often extremely beautiful. Saul adored beauty. But he disliked attention. “It’s too much” he would say, “why do people want more, more, more? More shows, more books? I embrace my unimportance.” Now that he is gone, his importance will only grow.

Our conversations often took a personal turn. He would talk intimately about his childhood in Pittsburg, his friendships, his loves, and his regrets. I once mentioned a difficulty that I was experiencing in my own life. Saul listened attentively. “Treat it lightly” he said, followed by one of his rippling, ironic and heartfelt laughs. I’m sure that is what he would say now, at his own passing: “treat it lightly.”

Saul Leiter passed away on November 26th, 2013.

Editor’s Note: The following essay was originally published August 19, 2009

Untitled, 1960 (c) Saul Leiter/ Courtesy Knoedler & Company in association with Howard Greenberg Gallery

Saul Leiter is sitting in the corner of his East Village studio apartment nibbling on a madeleine. The room is dense with photographs and paintings, piles of books, partially worked canvases, stacks of newspapers, and a collection of cameras, watches and pens, the last of which are arrayed like bouquets in cups. The putty-colored walls are peeling and a bank of north facing windows are without shades. “If you’ve spent a good part of your life being ignored, there are great advantages. People leave you alone.” He’s been left alone for almost forty years. “People are very taken with the idea of success. Everybody wants to be successful, except me.”

At eighty-five he has jovial eyes, tousled grey hair and an approachable but wary manner. He once bumped into the late photographer Helen Levitt in a bookstore. “You look familiar,” she said to him. He replied, “I am.” But he’s hesitant about public attention. “I often find that artists are self-serving when they talk about their work” he says, “and I don’t want to be like that.” There are other reasons for his wariness as well.

Up until just a few years ago Leiter was all but forgotten, just another elderly East Village resident shuffling to the corner deli to get a pint of milk. And yet in the mid 1950s his photographs had appeared in the Museum of Modern Art, he had exhibited paintings with William DeKooning and Philip Guston and, in the early 1960s, he had a number of prestigious photography assignments for Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue. His fashion spreads alternated with those of Richard Avedon’s. It was a promising start at a time when such early achievement often led to major art world success.

Leiter insists that he alone bears responsibility for his later obscurity and the inevitable poverty he suffered as a result. He was never a careerist. By temperament he prefers to work diligently and in relative isolation. A friend once said to him, “Saul, I’ve never known anybody who could resist opportunity as much as you.”

He reaches down and riffles through a stack of paintings that lie in an opened portfolio at his feet. These are abstract works, painted on small pieces of paper and vibrantly colored. He picks one up. “DeKooning liked this one,” he says with a trace of astonishment. “He liked the fact that I left on the toilet paper I used to dry it. That appealed to him.”

Leiter was making these paintings (which are appearing here for the first time on the web) at a time when, more famously, Mark Rothko and Hans Hoffman were exploring similar ideas and techniques. “A friend of mine told me that if I had just painted big I would have been one of the boys.” He lets out a rippling and ironic laugh.

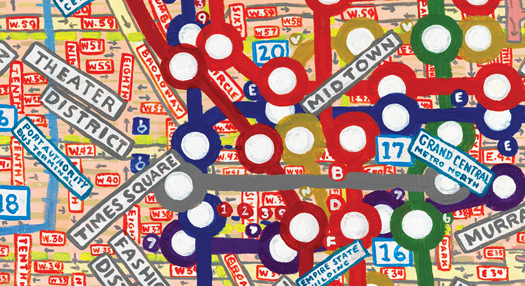

Souvenir, Paris, c.1965, gouache, casein and watercolor on paper

(c) Saul Leiter/ Courtesy Knoedler & Company in association with Howard Greenberg Gallery

The reasons for Leiter’s lack of recognition are complicated. It was partly due to his unwillingness to promote himself. Characteristically, he tells a story by way of explanation. While looking through a book recently, he came across a letter stuck between its pages. The letter, written in the mid 1950s, is from Betty Parsons, whose gallery famously helped launch the careers of many of the Abstract Expressionists, including Jackson Pollock. It’s an invitation to show work in her gallery. He never responded. Why? “I probably had to frame my paintings and I didn’t have the money.”

He admits to deeper reasons. Leiter is the son of an Orthodox Rabbi who was venerated for his Talmudic commentaries by a select group of scholars: “My father was a towering figure.” He had high expectations for his son. Leiter spent his early years in rigorous daily study both religious and secular; by the age of twelve he was reading Turgenev, Proust and Dostoevsky. But the religious side of his education did not hold. Instead, he was drawn to books about art, which he studied in the well-stocked Pittsburg University Library. He delighted in Peruvian tapestry, Tantric art and Japanese calligraphy. He devoured books about the western canon as well, fully absorbing Kandinsky’s explorations of abstraction as well as the work of Picasso, Matisse and Bonnard.

Inspired by his reading Leiter, with minimal encouragement or schooling, taught himself to paint. These early abstract works, dating from the mid to late 1940s, show a remarkably confident use of line, color and composition. The energy of his brushwork is palpable. When John Cage and Merce Cunningham saw a show of these early pain

tings when visiting the Outlines Gallery in Pittsburg in 1945, they bought one.

Leiter was still living with his parents at the time. His father did not approve. When a notice appeared in the local Jewish paper announcing a second art exhibition, his father actually wept with shame. Although he had been groomed since childhood to continue his family’s rabbinical tradition, he soon abandoned his theological studies. He boarded a bus at midnight and escaped to New York.

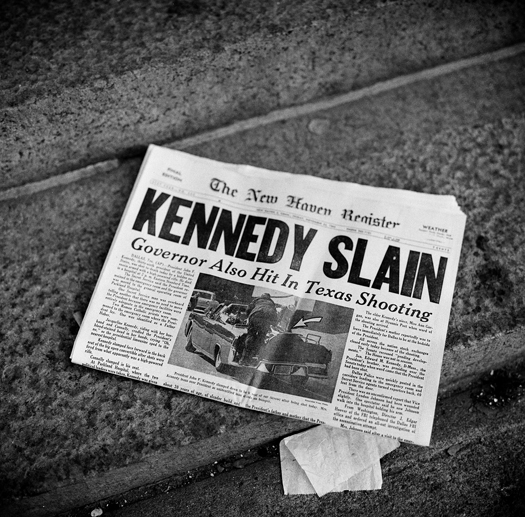

Snow, New York, 1960, chromogenic print

(c) Saul Leiter/ Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery

Leiter rises from his chair and snakes his way through the clutter. Talking about his life has triggered a memory. He digs through a teetering stack of his black and white photographs. “I have a picture of myself somewhere, where I am painting. I always worked on the floor.” He shuffles through the stack. A portrait of a young John Cage flashes by, followed by a series of languorous nudes and then a haggard looking Diane Arbus, who was a neighbor. He reaches the bottom of the stack and gives up with a sigh. He then smiles mischievously. “On my tombstone, not that I want a tombstone, it should read: ‘He tried but he couldn’t find it.’ ”

Seated back in his chair, he admits that he didn’t manage his life properly. “Maybe I was irresponsible. But part of the pleasure of being alive is that I didn’t take everything as seriously as one should.” Even while his commercial photography assignments were dwindling throughout the 1970s he continued to paint, entirely for his own pleasure. During the late 1980s, at a time when he was reduced to selling off books for extra money, he bumped into an old acquaintance. “You know, you used to be a big thing in the 1960s” the friend had said to him, “and now you are nothing.”

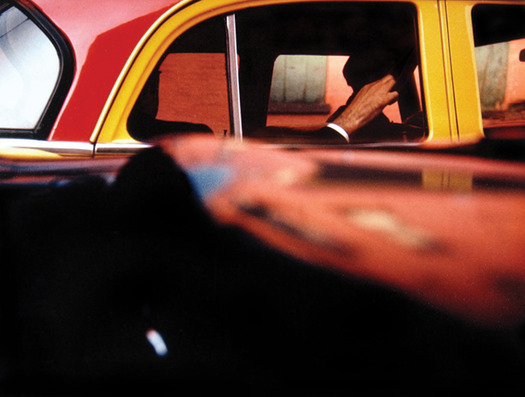

Taxi, New York, 1975, gelatin silver print (c) Saul Leiter/ Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery

That is changing. In the past few years, two books of his early color photography were published to great acclaim: Saul Leiter: Early Color edited by Martin Harrison and the monograph Saul Leiter. In these photographs, reality is broken up and made complicated by awnings and store windows as well as by reflections, deep shadows and weather, in the form of mist, snow and rain. It’s a distinctive visual diction whose haunting beauty derives in no small part from Leiter’s use of color: cadmium reds rhyming with silky blacks which are in turn set off by whites in a visual poetry all his own. The first edition of the book sold out almost immediately and sales of his photographs took off.

And now, in mid September, the Knoedler Gallery, in association with the Howard Greenberg Gallery, will be showing a selection of these early paintings, the first time this work will be seen by the public in years. Two more books, this time of his black-and-white photographs, are currently in the works.

Leiter views his late success with a poignant mixture of pride and loss. He seems genuinely pleased with the recognition while simultaneously anxious about the implications.

Together, we leave his apartment and slowly walk towards a local deli, where he is going to pick up some borsht for dinner. We pause on the street. “I’ve been resurrected,” he says ruefully as he turns the corner and waves goodbye.

For more on Saul Leiter, read Rick Poynor’s “Saul Leiter and the Typographic Fragment“.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Adam Harrison Levy

Recent Posts

‘The conscience of this country’: How filmmakers are documenting resistance in the age of censorship Redesigning the Spice Trade: Talking Turmeric and Tariffs with Diaspora Co.’s Sana Javeri Kadri “Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran A quieter place: Sound designer Eddie Gandelman on composing a future that allows us to hear ourselves think