June 10, 2020

Social Distance Learning: The Remote Generation

Literally overnight, words like synchronistic and asynchronistic, social distancing, and distance learning became buzzwords in the design education community. Although touted with the cheery prefix, ”Novel” don’t be misled; the coronavirus may be novel, there ain’t nothing novel about distance teaching; it has been around in some form another since prehistoric humans learned cave painting. The technology is, of course, millions of years more sophisticated today but the fundamental impulse must be the same. Distance learning is meant to convey knowledge and teach skill that will allow students and aspiring professionals to make marks that communicate messages, ideas and impressions . . . to others.

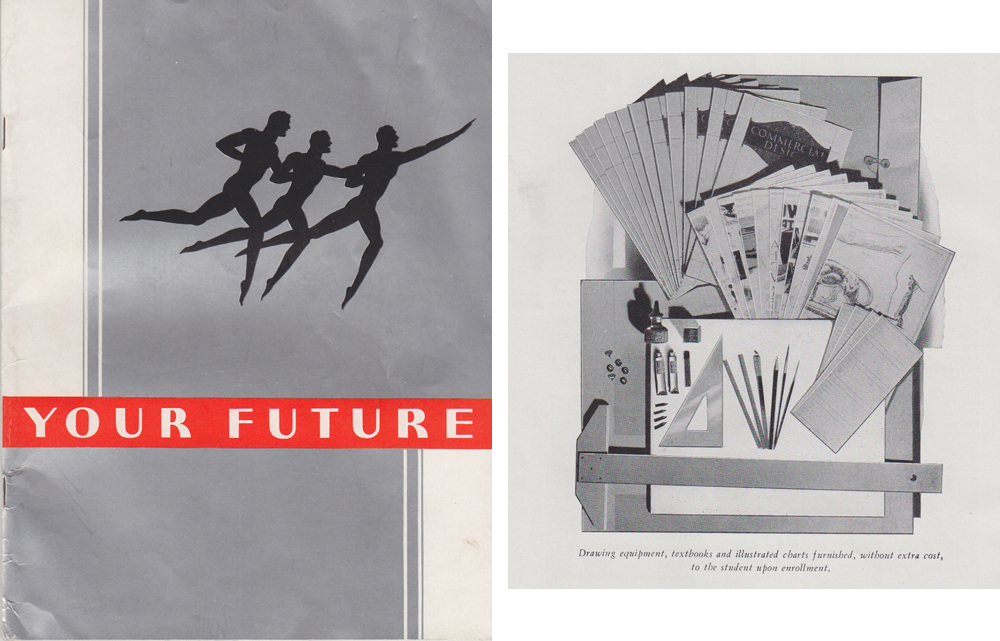

Skipping over those few million years, if you were faced with starting a new career, say, during a worldwide calamity like the Great Depression in the late 1920s or early ’30s and you had artistic aspirations, correspondence schools (a.k.a. distance learning) were an inexpensive way to do it. A booklet like Your Future (which is subtitled and How You May Realize It In The Opportunities Awaiting the Trained Commercial Designer) would convince you that “Commercial Illustration” was “A Well-Paid Profession” and that “Through Training You Can Grasp this Real Opportunity.” During the early twentieth century alone, in the United States, when advertising gave rise to a need for commercial artists and letterers, correspondence schools were founded to provide illustrators and designers with that real opportunity.

There were dozens, including The International Correspondence Schools in Scranton, Pennsylvania, Washington School of Art in Washington, D.C., The Lockwood Art Lessons in Kalamazoo, Michigan, The New York School of Design in New York City, Art Instruction, Inc. in Minneapolis, Minnesota and The Frank Holme School of Illustration in Chicago, Illinois (home of Oz Cooper). The leader, however, was The Federal School of Commercial Designing founded in 1919. The Federal School’s headquarters occupied a three story high, block long building in Minneapolis; had branch offices in New York City and Chicago; boasted over seventy-five advisors and full-time faculty members, was larger than any of the other schools; claimed over 3000 home study students annually enrolled and offered “a well-rounded, practical preparation for a profession.” What’s more they never saw an actual matriculating student.

The Federal School issued an opulent 64-page catalog in 1927 which questioned and answered:

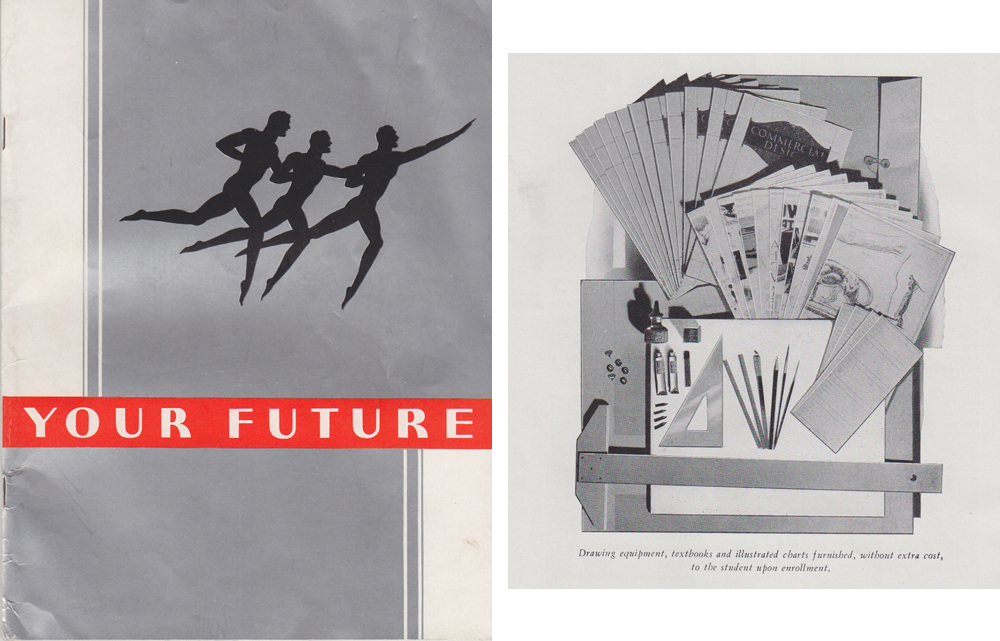

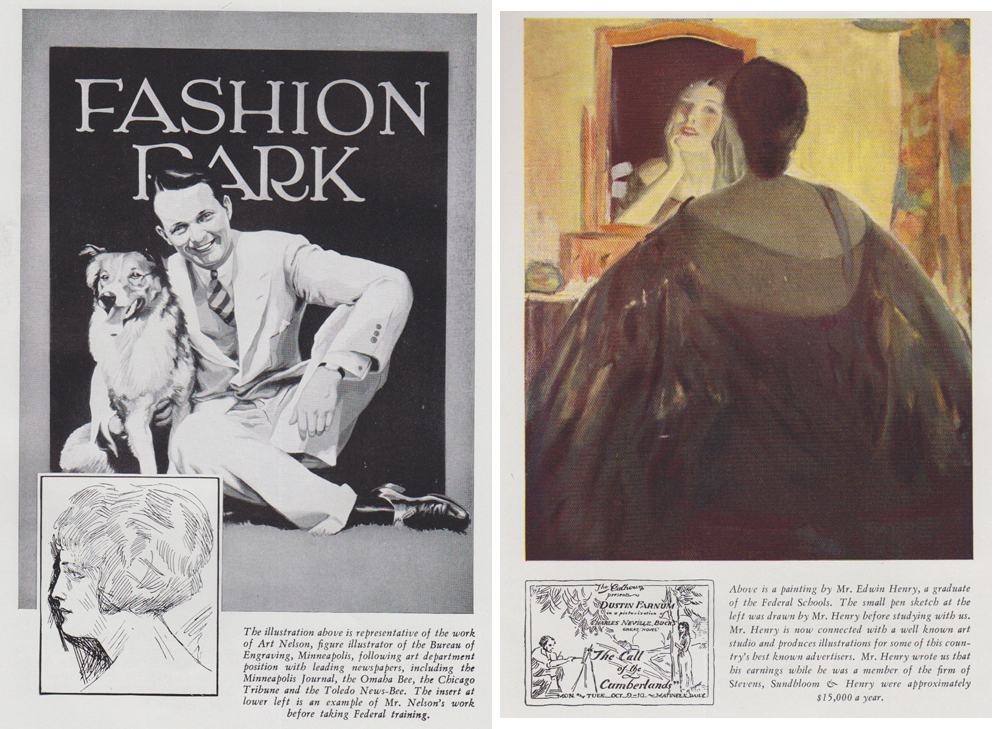

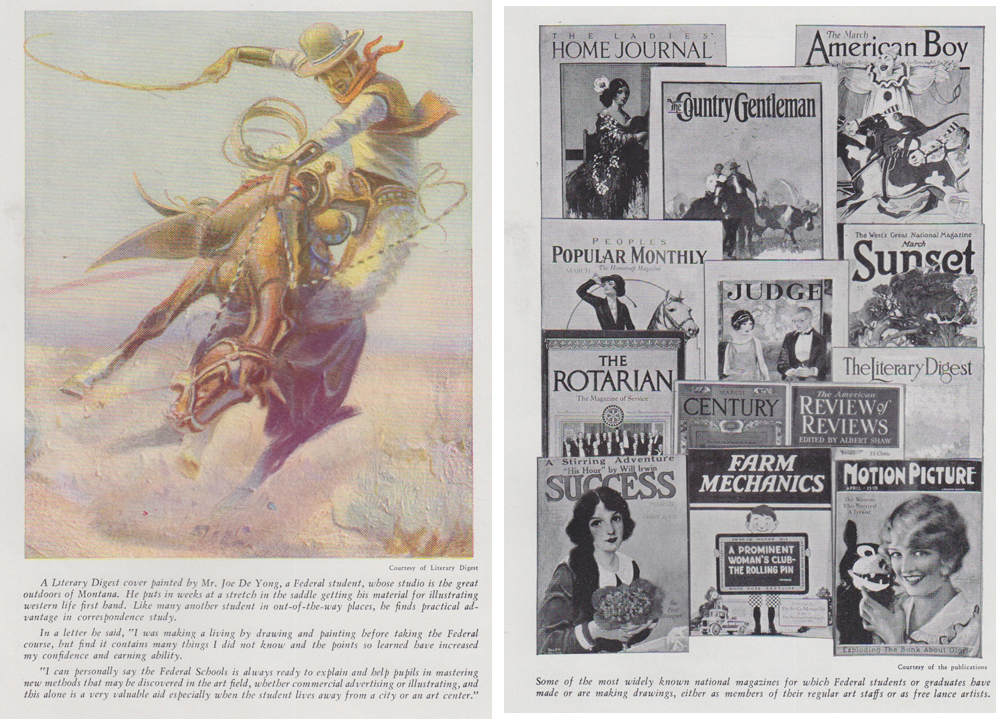

“What would you give to be able to draw professionally? Do you long for the ability to make splendid pictures, such as you see daily in advertisements, attractive story illustrations, richly colored magazines covers?” Profusely illustrated with photos of artists and examples of their work the Federal School lured prospective students to the practice of commercial art by invoking the glories of advertising, which the catalog declared was “the newest art, the youngest great creative force, in the modern business world.”

Once the otics and ologies were introduced through schools like the Bauhaus, education rose above the tricks-of-the-trade curricula, but back in the day, The Federal School approach offered a state-of-the-art education in a lucrative promised land through “the conscientious individual attention of the Federal faculty” which included teachers in advertising, fashion and animal illustration, booklet and catalog construction, general commercial art and posters, including poster designer C. Matlock Price, heralded “Painter with the Pen” Franklin Booth, Saturday Evening Post cover artist, Frank E. Schoonover, Good Housekeeping cover maestro Coles Philips, among others.

There were other distance learning legends: The “Draw Me!” ads promoting Art Instruction Inc. on matchbooks and in magazines that began in the 1930s and continued through the 1960s, offered “Your big chance.… An easy-to-try way to win FREE art training!” The International Correspondence Schools guaranteed a whopping “366 percent increased income” and a “1000 percent interest” on the investment made in its Sign Lettering Course, but this and other come-ons actually masked the serious nature of the well-rounded courses. In the 1920s and 1930s resident art schools charged an average of $300 annually as compared to an average of $75 to $100 for the correspondence school and entailed anywhere between one and four years of study during which time matriculating students were often unable to earn steady incomes.

As the Federal School catalog boasted “the cost for tuition of such schools will average much higher than the tuition of the Federal School — to say nothing of your living expenses.” The home study course further offered the benefit of measuring progress by the student’s own ability to advance. The Washington School of Art proudly noted in its 1928 catalog that “We take great pains with backward students.” And the International Correspondence School’s 1929 catalog reassured its more challenged aspirants: “Don’t hesitate to enroll because you lack an education.… Courses include punctuation and a 25-cent pocket dictionary will give you the correct spelling of all words you will likely have occasion to letter.”

Even women, who were not encouraged by the “resident” schools, were singled out as beneficiaries of a correspondence education: “Yes, you read it right,” declared the Federal School’s catalog. “It’s true. Woman are constantly taking a larger place in the modern commercial world.… Buyers of commercial art will just as readily buy from women as from men.…”

A standard no-residency, remote learning course included a dozen or so text-lessons and workbooks that taught practical approaches to drawing, composition, lettering, typography and more. The Federal School and Art Instruction Inc. both offered a unique twelve lesson course — what they called “divisions” — presented in a series of surprisingly clear, entertaining and profusely illustrated booklets, illustrated with some of the most fashionable and award-winning work of the day. Each division included step-by-step introductions to a variety of skills, crafts and analyses, such as Federal’s “blocking in” with pencil and crayon in Division One, lettering — historical and modern — in Division Four, retouching photographs in Division Seven, artistic covers and title pages for booklets, catalogs and circulars in Division Eleven and reproduction methods in Division Twelve. Schematic diagrams enabled the student to work start work immediately. And a foreword to each division booklet proposed methods for studying, such as how to acquire a firm understanding of the principles, how to do the practice exercises and ultimately how to prepare the work to be submitted for criticism.

Individuality was extolled. “You are in a class by yourself,” asserted the International Correspondence Schools’ 1928 catalog, Show Cards and Signs. “The instructor attends to you alone; you are encouraged, counseled and guided at every step.” This was accomplished through frequent reviews of assignments designed to keep the student on a forward track.

Training manuals, workbooks, lesson charts and exercises were prepared by staff members based on study guidelines established by the luminary faculty, who were really only nominal teachers and rarely set foot on the school’s premises. Of course, there was no Zoom room for students to gather in yet like clockwork, once every couple of weeks assignments would be completed and mailed to teachers who would mark them up and offer tips. Most instructors were hired either full- or part-time to evaluate the assignments, write detailed reports and offered students personal tips, such as Federal instructor and newspaper illustrator C.L. Bartholomew’s shortcut for drying wet paint with the hot lit end of a cheap cigar. Teachers might be assigned an exclusive group of students or share them among other instructors. The student never spoke to or met the instructor, but mail relationships were nurtured to provide the student with a mentor. Students were given as much time as necessary to complete a project or particular phase of instruction.

All these programs issued certificates of accomplishment to students who completed the course. But if for any reason the student was “not absolutely and unqualifiedly satisfied with the results of his or her study, provided written application for such refund is made within thirty days from the date the student completes the course in accordance with the rules of the school,” as the Federal School promised, the full tuition would be refunded. According to the schools’ own literature, such instances were rare because the schools enrolled students found their calling, as in this testimonial for International Correspondence School: “Your course has done for me what it will do for anyone else if they enroll and study. I now have my own shop.… The last week in June and first week in July I made $100…I’ve had my I.C.S. diploma framed and feel very proud of it.”

Correspondence schools were operating as early as the 1890s and the 1920s through the 1950s was the heyday. The Famous Artists School in Westport, Connecticut was founded, in 1947. The Famous Artists School began its full page advertising campaign in national magazines which showed its renown illustration faculty, including Norman Rockwell, Stevan Dohanos, Coby Whitmore, Albert Dorne and others (the so-called Westport School of American illustration), sitting around a table. The Famous Artist School, which focused exclusively on illustration, had its honored faculty develop classes, while part-time instructors reviewed and critiqued the student work. The Famous Artist School merged with Cortines Learning International in 1981 and still operates today, but the correspondence art school movement was overshadowed in the late 1960s by art and design schools both fulltime and continuing education classes. Today the terms is remote or distance learning. No doubt, with the genie out of the Covid-19 bottle, the trend will continue. In the post-Covid age design teaching may soon migrate more to remote model than had ever been anticipated. But keep in mind as different as it may seem, it is not as novel as it appears.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Steven Heller

Related Posts

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

The Observatory

Ellen McGirt|Books

Parable of the Redesigner

Arts + Culture

Jessica Helfand|Essays

Véronique Vienne : A Remembrance

Recent Posts

Mine the $3.1T gap: Workplace gender equity is a growth imperative in an era of uncertainty A new alphabet for a shared lived experience Love Letter to a Garden and 20 years of Design Matters with Debbie Millman ‘The conscience of this country’: How filmmakers are documenting resistance in the age of censorshipRelated Posts

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

The Observatory

Ellen McGirt|Books

Parable of the Redesigner

Arts + Culture

Jessica Helfand|Essays

Steven Heller is the co-chair (with Lita Talarico) of the School of Visual Arts MFA Design / Designer as Author + Entrepreneur program and the SVA Masters Workshop in Rome. He writes the Visuals column for the New York Times Book Review,

Steven Heller is the co-chair (with Lita Talarico) of the School of Visual Arts MFA Design / Designer as Author + Entrepreneur program and the SVA Masters Workshop in Rome. He writes the Visuals column for the New York Times Book Review,