Because it’s so hard to get lost these days, what is the history of being found?

In 1907, Andrew Rand McNally II, the grandson of the co-founder of Rand McNally & Co, went on his honeymoon. He lived in Chicago and planned to drive to Milwaukee. But driving then was not like driving now. Most roads were rutted, unmarked, and unpaved, not much more than dirt tracks originally intended for wagons. In 1903 there was only 161 miles of paved highway in the US.

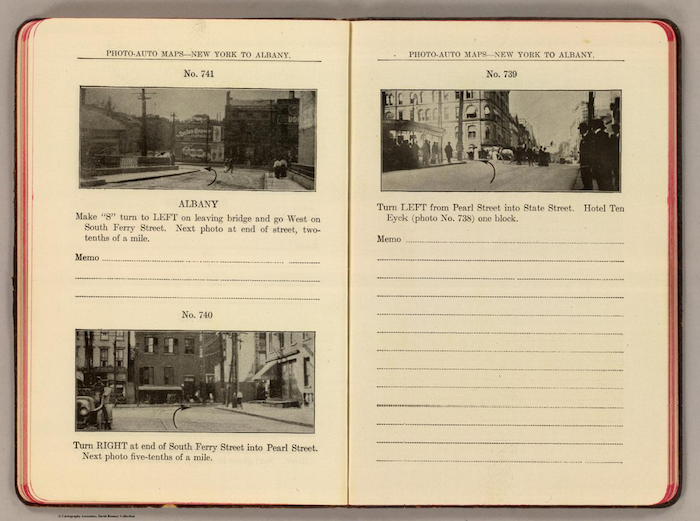

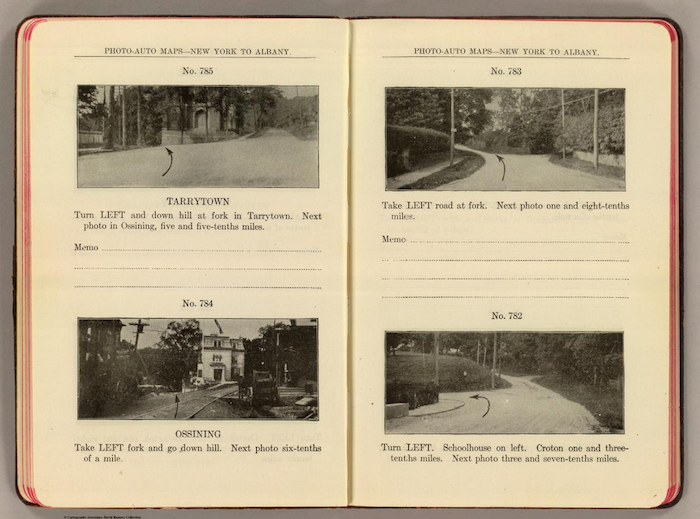

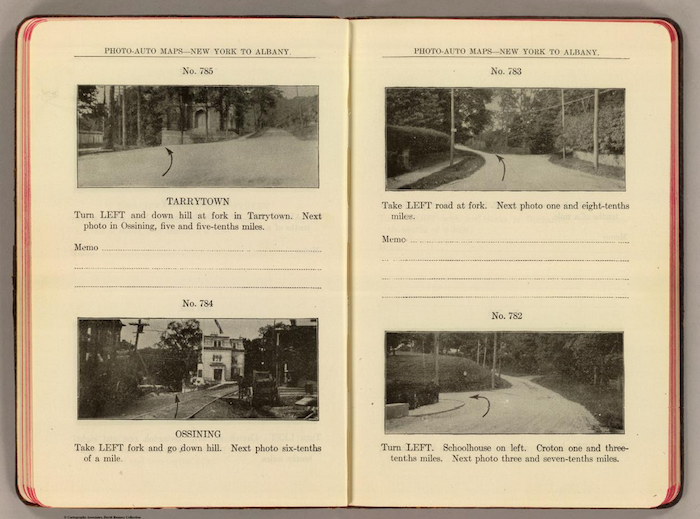

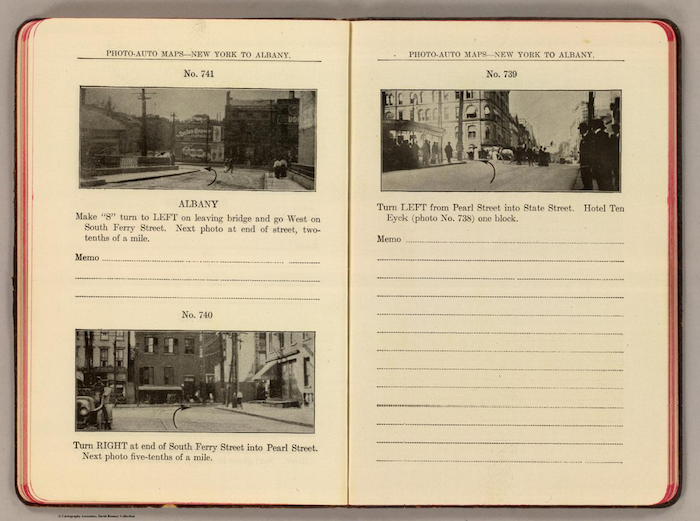

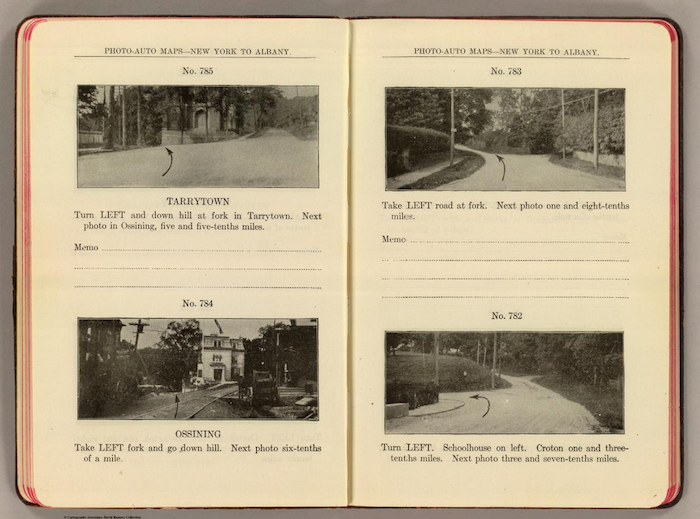

There were few road maps and hardly any names for roads (the system of road numbers was to come later, in 1917 when John Brink, an employee of McNally’s, came up with the idea). Getting from here to there meant following carriage tracks, asking directions, and navigating by landmarks: turn right at the farmhouse; follow the bend of the road over the hill; keep the courthouse on your left. McNally had the vision to change that. He strapped a camera to the front fender of his car and at every junction he stopped and took a photograph. He did the same on the return journey home (posterity does not record what his new bride felt about this).

Back in Chicago the photographs were printed—with arrows indicating which way to turn—and bound in leather. It became part of the Rand McNally series Photo-Auto Guide. Twenty-five editions (i.e. New York to Albany, Chicago to Rockford) were published over the next five years. McNally’s images were utilitarian. They had none of the visual poetry that we now associate with later photographic road trips: Robert Frank’s The Americans or Garry Winogrand’s 1964.

The Photo-Auto Guides were the forerunner of an image based way-finding system of seismic impact: Google Street View. Before Street View came to dominate the visual how-to-get-there scene, maps were the way to go. Remember those crinkly over-sized panes of paper, impossible to refold and prone to rip?

What makes an old-style map so compelling (or frustrating, depending on your point of view) is mystery: do we take Route 22 or Route 40? Which road is more picturesque? Which road is clogged with stoplights? The only clue is the color-coding of the printed line, and of course, the experience of the trip itself.

The

Photo-Auto Guide changed that; it allowed a traveller to preview images of the trip before departing. They were a proto-virtual tour. As a result, some of the mystery of travel was lost, but a degree of precision was gained: it’s helpful to know to take a right at a junction, especially if you’ve already previewed what the turn will look like.

Crucial information, especially if you are on your way to Milwaukee for your honeymoon.

++