February 26, 2007

The Other Monocle

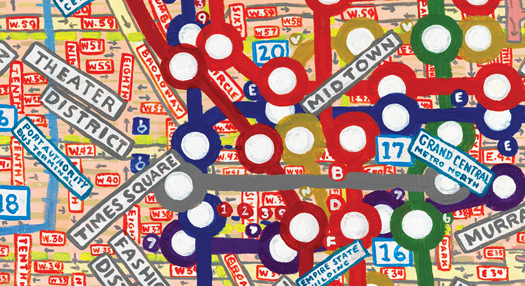

Monocle, cover detail, design by Phil Gips, 1963.

A whole lot of blog hoopla has been recently generated about Monocle, the spanking new art, culture and issues magazine from Wallpaper’s creator Tyler Brûlé. He’s the guy who brought neo-classic post-European modernism to lifestyle publishing. Although Monocle looks nothing like its predecessor, it promises to be the next new thing in integrated web and in print publishing — a very laudable endeavor to be sure — deserving serious analysis and review. But this is not going to be that. In fact, this is not even an article about Brûlé’s magazine at all — but rather a look back to another, virtually forgotten but decidedly important, magazine with the very same name — one that published under the motto, “In the land of the blind the one-eyed man is king.”

This earlier Monocle was the smartly literate and hilariously funny American satirical magazine, published from the late 1950s (as stapled pamphlet and assorted newsletters) through the mid-1960s (as a perfect bound magazine) edited by Victor Navasky, currently editor emeritus of The Nation. This Monocle, headquartered at 80 Fifth Avenue in New York, had the distinction of predating many of the sixties most important alternative publishing institutions, like the “new left” monthlies, Evergreen Review and Ramparts, and was precursor of The National Lampoon. Arguably, it also influenced Esquire (during its golden years under Harold Hayes, when George Lois conceived its covers), New York Magazine (under Clay Felker and Milton Glaser), and even Spy magazine (edited by Kurt Andersen and Graydon Carter). It also had impact on the look of some underground newspapers. Many of the artists, cartoonists, designers and writers who contributed to this so-called “leisurely published” (at first lazily twice a year) Monocle seeded much of the alternative press and mainstream publishing industry, and many are still active today.

Monocle was started while Navasky was still a student at Yale during the tail end of the McCarthy period. “There was what I thought of as an ‘irreverence boomlet’ going on, and we thought we were part of it,” he recalled in a career-spanning interview on the website of the Institute of International Studies at UC Berkeley. “Mort Sahl [the political monologist] was out in San Francisco at the ‘hungry I’ nightclub; Nichols and May were improvising in Chicago, and we started Monocle magazine. There was another little magazine called The Realist, a journal of free thought, criticism and satire that Paul Krassner had coming out of New York, and we thought we could challenge the pieties of the day through satire, which didn’t really exist in print in a serious way at that point.”

Careers were made and styles launched at Monocle. The list of contributing satiric illustrators is a who’s who of political acerbity and editorial acuity: Robert Grossman created the first African-American superhero, “Captain Melanin,” and “Roger Ruthless of the C.I.A.,” while Ed Sorel, David Levine, Paul Davis, Randy Enos, R.O. Blechman, Bob Gill, Milton Glaser, James McMullan, Tomi Ungerer, Lou Myers, Seymour Chwast, Marshall Arisman and John Alcorn contributed covers, cartoons and illustrations that poked gapping holes in the body politic and its sanctimonious leaders on both sides of the aisles, elected and otherwise. Together they triggered a golden age of conceptual editorial illustration eventually adopted by The New York Times OpEd page (which today receives the lion’s share of the historical accolades for this genre of art). Their trenchantly witty writers included some of today’s literary and social comedic luminaries, Calvin Trillin, C.D.B Bryan, Dan Wakefield, Neil Postman, Richard Lingeman, Dan Greenberg, and humorist Marvin Kitman, who became a commentator and TV critic for Newsday. With brazen hubris Monocle even ran Kitman for President of the United States in their Spring 1964 issue (the year LBJ ran against Goldwater), the first time in the twentieth century a comedian ran for the high office (pre-dating Al Franken by over forty years). In the same issue, Chas B. Slackman offered his timeworn vision of “The Composite Congressman,” showing a faint heart, strong stomach, hip pocket in which he hopes to keep his district, and pocket bulging with franked junk mail for constituents, among other things. There were also parodies of certain verities, like Sorel and Chwast’s “Cold War Cutouts,” a patriot’s pastime for people on both side of the Iron Curtain, inspired by hyperbole in speeches by Kennedy and Khrushchev.

For Monocle looks were not everything, but the unique design gave the magazine great allure. As art director, Phil Gips, later of Frankfurt, Gips and Balkind, introduced Victorian wood types to the layout and it was a revelation. The eclectic typefaces supplied by Morgan Press, the leading distributor in the United States of vintage type, were a fresh alternative to the Swiss style with its preponderance of Akzidenz Grotesk and Helvetica. Five years before the Hippy flea market aesthetic and twenty years before postmodern “retro,” Gips introduced nineteenth century pastiche — and did it beautifully. Sorel (who spent considerable time sleeping in the Monocle office) also helped compose the ornamental display typography. When I was first starting out as an art director for underground newspapers in the 1960s, I’d buy second-hand Monocles simply to cut out the type and paste them onto my own layouts.

Vintage type was endemic to the magazine’s personality, but when “Monocle Goes Quarterly” in 1963 it adopted an unconventionally tall narrow format developed because, Navasky said, being “as tall as Time and as wide as Reader’s Digest we thought we could sell ads prepared for both [of these publications].” But it didn’t work, in fact it “caused problems with the printer because we wasted paper.” Few paid ads were ever realized and the magazine was chronically in the red.

Finances aside, Monocle was neither ideologically red or pink but rather contrarian. In the Summer/Fall 1963 issue, only months before John F. Kennedy’s assassination, the “Lord of the Hawks” article sharply critiques Kennedy and his brain trust for saber rattling in the Vietnam War. Monocle also took no-holds-barred swipes at both Johnson liberals and Goldwater conservatives, CIA interventions and civil rights disruptions — one issue included Tomi Ungerer’s famous commentary, “Black Power/White Power,” a pox on both houses. In Kitman’s ongoing campaign it was never clear exactly what side he was on — the right? Left? Libertarian? Or was he just plain-old independent? “At Monocle we [thought] that the ideal magazine should be like the UN police force and come out whenever there’s an emergency, or come out when we had something to say,” explained Navasky about its irregular schedule and regularly skeptical stance.

So today a new Monocle is on the stands and internet, which its publisher and investors hope will be as popular and influential as Wallpaper. But I wish they had selected another name. Like great sports figures’ numbers, Monocle, which ceased publishing in 1965, should have its name exempt from appearing on any other magazine (unless, of course, it’s as great as the original).

Steven Heller is co-chair of SVA’s MFA Designer as Author Program and editor of AIGA Voice. His website is hellerbooks.com.

Copyright © 2007 Steven Heller.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Steven Heller

Recent Posts

Mine the $3.1T gap: Workplace gender equity is a growth imperative in an era of uncertainty A new alphabet for a shared lived experience Love Letter to a Garden and 20 years of Design Matters with Debbie Millman ‘The conscience of this country’: How filmmakers are documenting resistance in the age of censorship

Steven Heller is the co-chair (with Lita Talarico) of the School of Visual Arts MFA Design / Designer as Author + Entrepreneur program and the SVA Masters Workshop in Rome. He writes the Visuals column for the New York Times Book Review,

Steven Heller is the co-chair (with Lita Talarico) of the School of Visual Arts MFA Design / Designer as Author + Entrepreneur program and the SVA Masters Workshop in Rome. He writes the Visuals column for the New York Times Book Review,