Alexis Haut|Education, Interviews, Moving Pictures

December 1, 2025

‘Thoughts & Prayers’ & bulletproof desks: Jessica Dimmock and Zackary Canepari on filming the active shooter preparedness industry

HBO’s new documentary, helmed by two lauded photographers-turned-parents, excavates the $3B market born from America’s school shooting problem.

Is surviving a school shooting a design problem? The $3 billion active shooter preparedness industry believes that the answer to that question is, unfortunately, yes.

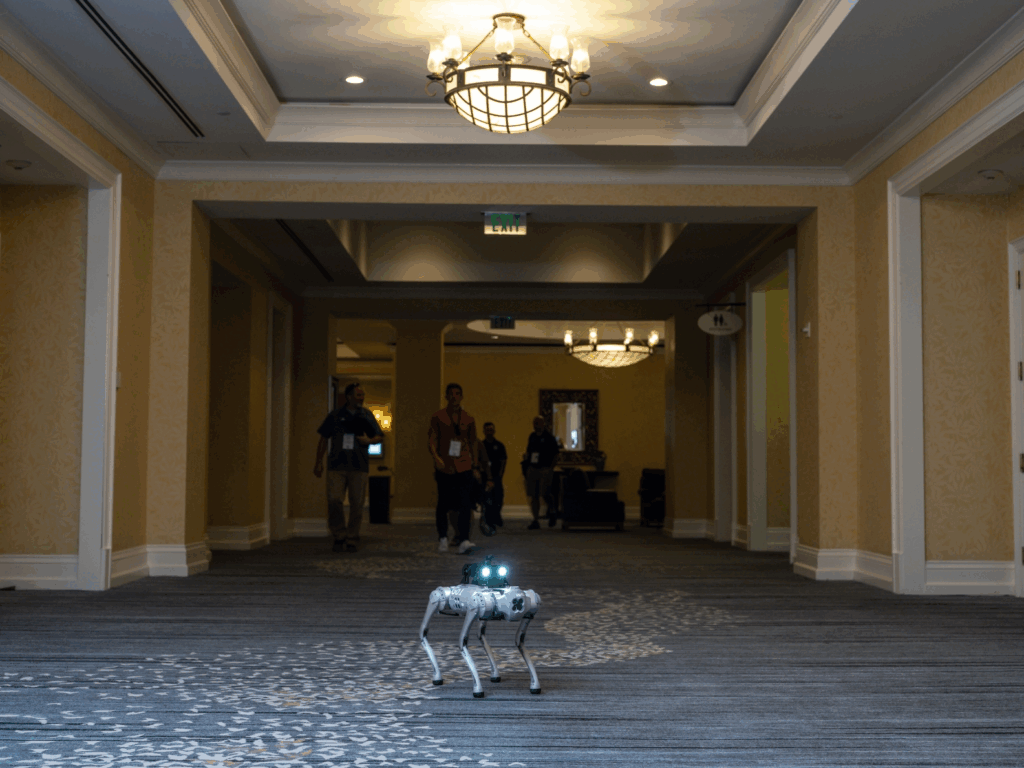

No, you didn’t hallucinate that sentence. There is a $3 BILLION American industry of products and services designed to boost a kid’s chances of surviving a school shooting. We’re talking bullet proof backpacks, tactical robot dogs, and skateboards that double as shields. Beyond physical goods, teachers can enroll in strategic gun training, and schools can contract companies to stage a mass shooting event in their cafeterias and classrooms.

It’s almost stranger than fiction. Certainly more horrifying to this former middle school teacher. A country that lacks meaningful gun reform has filled the void left behind by immeasurable loss the best way it knows how: with capital.

Thoughts & Prayers: How to Survive an Active Shooter in America, which premiered on HBO November 18, captures the surreal landscape of safety rituals in American schools and communities.

The documentary is co-directed by Jessica Dimmock and Zackary Canepari. Both are photographers whose bodies of work focus on portraits of American life, especially the painful parts. Dimmock first made a name for herself in the international photography world with her 2007 book The Ninth Floor, a collection of hundreds of photographs of heroin users who moved into a Manhattan apartment owned by a former millionaire.

For his part, Canepari directed the 2016 documentary T-Rex about Flint, Michigan boxer Claressa “T-Rex” Shields. Stills of T-Rex were released as a photography book, Rex, which won Pictures of the Year International’s Best Photography Book award in 2016.

Flint, Michigan, with its unique and uniquely American challenges — like the Flint water crisis and the economic despair left in the wake of the dwindling auto industry — continued to be creatively generative for both Canepari and Dimmock. They co-directed the 2018 Netflix documentary series Flint Town about policing in the city.

Somewhere along the way they became a couple and had a child. Those milestones, and the “weird Google searches that we ended up doing around school safety,” birthed Thoughts & Prayers, says Canepari, who also served a brief stint as a teacher. “That just led us down a creative wormhole because we felt there was such a level of absurdity to all of it.”

The resulting film leans into both the creative and absurd. Dimmock and Canepari frame their shots as artfully as still photographs and use an operatic score to soundtrack frighteningly realistic scenes of rehearsed active shooter events.

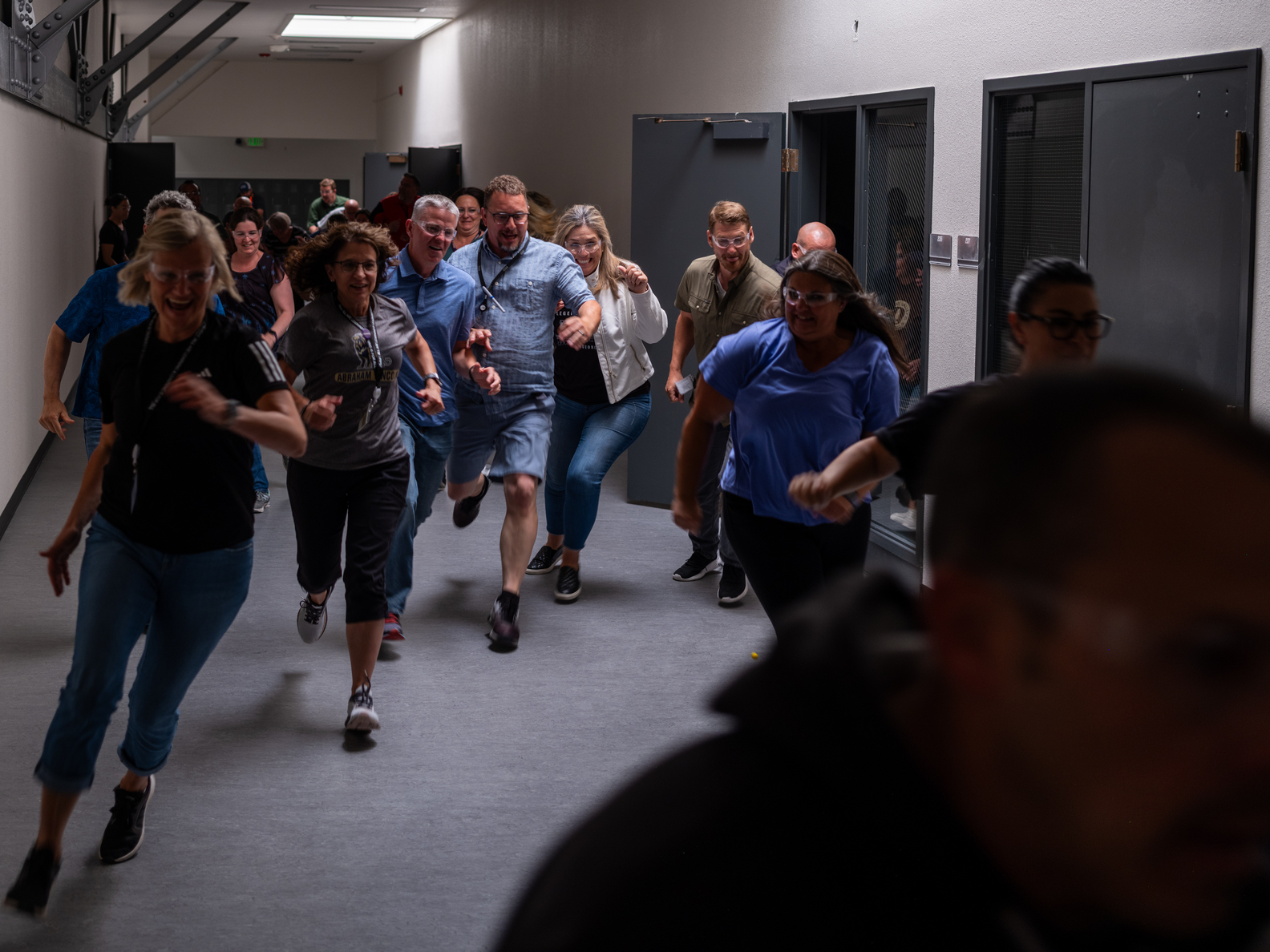

Over the course of 85 beautifully rendered but tense minutes, viewers visit three towns across America to explore different safety preparations. In Medford, Ohio, we meet Summer, a high school student who is understandably anxious about an upcoming staging of a mass shooting at her high school. In Provo, Utah, AP Chemistry teacher Rachel breaks down the tragedy and urgency of participating in a teacher gun training program. And in Long Island, siblings Quinn and Kannon participate in a town-wide mass shooting simulation where they play gunshot victims, complete with gruesome makeup and prosthetics. Peppered throughout are interviews with the creators of the products and trainings meant to help people like Summer, Rachel, Quinn, and Kannon survive a shooting.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Alexis Haut: Tell me about how this documentary got started.

Jessica Dimmock: Originally, we thought of this as a still photography project. But as we were confronting the absurdity that our child was going to be faced with, we were kind of like, what would it be like to look at your average everyday American active shooter drill? What would it be like if you could look at the classroom and see a little huddle of kindergartners hiding under their desk or in a little pile in the corner? Wouldn’t that be so disturbing?

One of the things that makes it so disturbing is, five minutes earlier, they were practicing their ABCs, then they paused to practice for mass death, then they went back to their ABCs. And it was like, all right, well, to get that across, we’re talking about movement and film. And so then it kind of morphed into a documentary.

AH: Your background as photographers is also obvious in the aesthetic of the film. How does photography inform your work in motion?

JD: We wanted a heightened reality. And then we really got interested in how some of these things happen so quickly. Some of the more elaborate drills go on for a few hours, but your average one is over in a minute or two. So we also looked at cameras that would allow us to shoot in super slow motion so that we would really slow down time, and then the movement would become beautiful again. And with this kind of operatic score, we would be making a bit of an American opera over this weird ritual that we all do. How do you make people look at the thing that they don’t want to look at? Our solution was, let’s try to make something that’s deeply ugly beautiful again.

Zackary Canepari: The drills and demos happen all the time, but they happen very quickly, so we’re not really able to film for hours and follow people around and really get into people’s lives. So I think it really pushed us to think formally about how we approached each subject. We had a lot of rules about how we could shoot stuff — just trying to be consistent and create a language for the audience that felt a little bit arm’s length, right? Like there’s some personal intimate moments for sure, but we’re trying to be mostly observational without over-editorializing with our cameras. We’re just like, here’s what it looks like.

AH: One thing that struck me is that we hear your voices from behind the camera responding to the person you are interviewing, which is not something that usually happens in documentaries. It made me consider you, the filmmakers, as people. How did making this film affect you, especially as parents?

JD: There’s one point when Quinn and Kannon [the students from Long Island] are having their little moment when the sister is admitting that she keeps a readiness bag in her backpack to help her classmates if they get shot. I, just as a human, forgot my role as filmmaker for a second. You hear me off camera. I get really upset and say, ‘that’s horrible.’ I forgot myself in that moment because, in the moment, it was this girl in front of me, and I was just as upset as her brother was to hear that.

ZC: We were motivated to make this film because we are parents. Our kid goes to school down the street from us in Brooklyn. She has had some shelter in places and some lockdowns from some gun violence around the school, not in the school. And I’m kind of embarrassed to admit this, but we, as just normal civilian parents, we’re not asking tough questions of the school or really understanding what the school is doing in those moments. And, you know, we have to be really clear that our film is not a criticism of programs or trainings or lockdown. I want my kids’ school to be prepared because this is the world we’ve decided to live in. We represent the audience, too — the audience that just doesn’t know what all this really looks like.

AH: How did you land on the three locations of Medford, Provo, and Long Island? How did you find these stories?

JD: Well, we wanted to represent three different types of preparedness trainings. We knew we wanted to see one of these big mass casualty exercises — the one that we see in Medford. They’re happening all the time in little towns across America. We just knew that we wanted to find out about one early so we could really go into the planning and preparation and see what those conversations were. So we chose Medford because we had an opportunity to get in early.

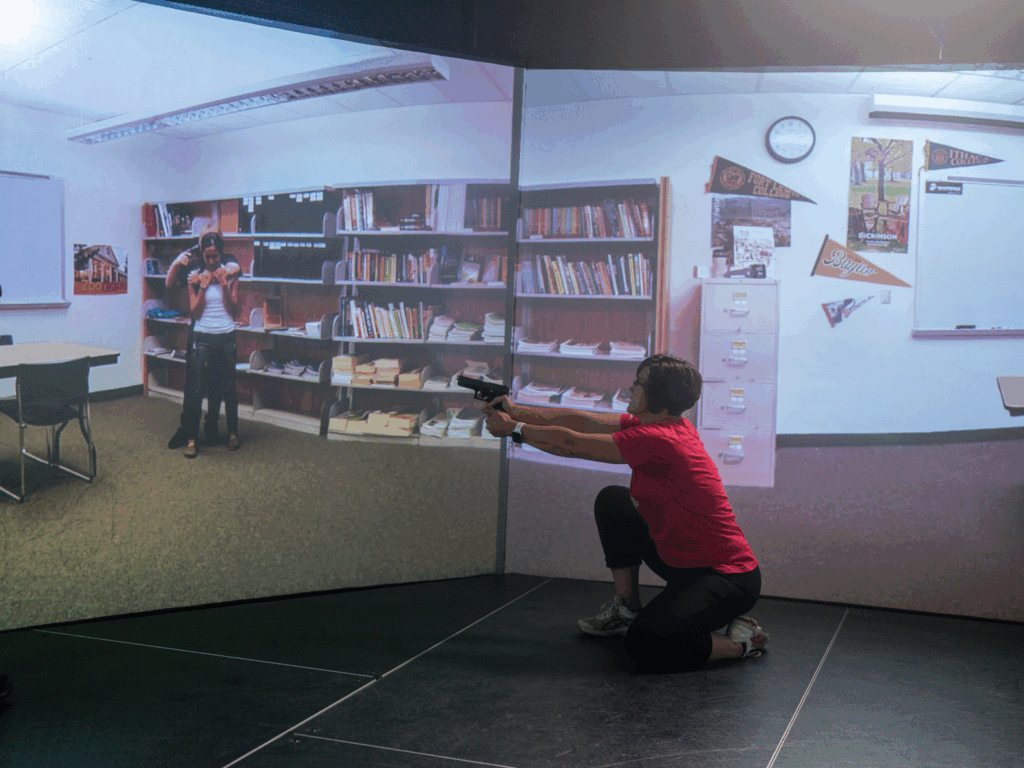

We chose Provo because that was where teachers are doing one of the things that is suggested often as a solution, which is, just arm the teachers. And when you look at what that really looks like — no shade on any of those educators — it’s not what they went to school for.

And then in Long Island, it’s a scenario where they really involve the students in the gore. We had seen it in a photo essay, and so we wanted to also get into that hyper-realism of the gore, and the kids’ involvement, really acting out the injuries.

AH: The people featured in your film are teachers, students, and those selling these preparedness products and trainings. You don’t get the typical documentary approach of interviewing the journalist or the academic or even parents. So I’m curious about who isn’t in the film.

ZC: We were just very disciplined in who we wanted to hear from in the film, and I think it was obviously the kids. With the teachers, I think what’s so interesting is that they’ve been asked to be on the front lines of every American issue: cultural masks and book bans and, obviously, gun violence. And how did that look when we were in a firearm training program in Utah? Like, how did that play into the psyche of these teachers? It wasn’t very hard to get the teachers to have pretty complex feelings about where they were at.

Rachel, the teacher who’s featured most in the film, has this great line where she says, ‘there’s been so much drop-off in teachers. The ones who are in this gun training program are the ones who are left. And they’re willing to go this distance in order to continue to teach kids AP chemistry.’

AH: As a former teacher, I found Rachel to be one of the most affecting interviews. I left the classroom in 2018 and honestly all of this — the products and technology — has gotten so much more sophisticated. When you were speaking to the people who are making products or running trainings, did you get the sense that these things were helpful?

JD: It’s very hard to prove that any of this stuff is going to be effective when you really get into the numbers of what it would cost to do this at schools that are notoriously underfunded. When you think about the resources being used, these products certainly don’t get to the underlying issue of why this happens. We have a fair amount of skepticism toward most of them.

In terms of the individual manufacturers and innovators, there’s a little bit of predatory behavior here for sure, and opportunism, but they are trying. And so we’re always trying to make sure that, while we’re presenting this through a somewhat absurdist lens, we are not losing sight of the fact that our criticism is with the violence and not with the industry that’s created as a result of the violence.

I can think of some other ways that we might solve this, but the products in and of themselves might have some good ideas, but you change one variable, and everything goes out the window. Like, the thing that locks the door only works if the shooting happens when they’re in the classroom. What if they’re in the hallway? What if a kid goes to the bathroom? What if it happens during lunch? There are just endless permutations of how it could go and how it would not work according to plan, especially when you’re dealing with an AR-15.

ZC: We really wanted to be inside of capitalism. It’s very American. And we always say that we don’t take products off the market in America. We just add new products to offset the other products. There’s a big old void left from gun violence. And these products are filling that void. I think that’s a very American response. And again, the products aren’t the problem. Training programs aren’t the problem. Lockdown drills aren’t the problem. The problem is something totally different that we’re not dealing with. And I think the film is saying that by not saying it.

AH: There’s this one line in the film that I think encapsulates your whole point. The man who sold bullet proof shields made to look like skateboards and photographs said, ‘Every time there’s a tragedy, my family financially benefits.’ There’s just so much in that statement. Were there any products or services that really seemed particularly outrageous to you?

JD: There’s one that I remember: this bulletproof desk. It’s basically a desk that’s a little cubby. And when the drill goes off, all the students crawl inside of it and close this bulletproof door. And when I think about the practicality of that, I’m like, okay, so what does the student [who doesn’t fit] do? How much does this thing weigh? I mean, it’s hundreds of pounds per desk. So I’m thinking about, okay, per floor, you need 30 of them in a classroom times 10. Are the floors even equipped to deal with this amount of weight?

ZC: I think the showstopper is the robot dog. It can be outfitted with various tools to help stop an active shooter. And it exists in a couple of schools. I mean, that obviously is very dystopian, Black Mirror-ish. We didn’t include one of my favorites, which is the taser drone a few companies are now developing. It’s exactly what it sounds like. If somebody comes into the school with a gun, it just drops down, starts to rotate, hovers like a drone, and then some remote operator drives it at the intruder and shoots them with tasers. I thought it was kind of great.

JD: Maybe that’s a great idea. Maybe that would work. Or we could regulate guns, you know?

AH: The amount of money and research and time that’s put into something like that.

ZC: It’s also like, for the high school that had the mass casualty drill in Oregon, it took a year for them to do that. It was a lot of time, a lot of resources, a lot of energy, a lot of different organizations coming together. So in a lot of ways, there’s community building in there, but at the same time, what could that community have done if it had spent its time doing things that were not planning for mass death?

JD: And that’s the cost, whether or not it costs dollars. Although certainly, there’s also lots of contracts that these companies and programs secure, and lots of dollars are being spent on this stuff. Schools could be spending time and money on a new curriculum, a new approach to learning how to read, a new phonics program, a new math approach.

And so, the former teacher in me, my blood boils when I think about all of the time and energy and effort going toward this because it’s so hard to get anything in a school.

AH: And there is a psychological cost as well, of course. Before a scheduled drill, you’re completely distracted by it, stressed out, anxious. And then afterward, it takes a good 30 minutes to get everybody back to a baseline of normal, to sit down and read a book again, you know?

ZC: There’s also a mundaneness to all of this that I think is equally as disturbing and sad. Just like being on your phone for 15 minutes, 10 minutes, or however long the lockdown drill is, looking at TikTok videos or texting with your friends because you’re so numb you’re not even thinking about what this drill is about. It’s just not a sign of a healthy country.

AH: I do appreciate that you eliminated graphic violence from your film. There is one scene in particular where there is the audio of the shootings, but you played footage of tornadoes over it. I thought that was quite well done.

ZC: We have learned the hard way, I think, with this film, just how visceral this subject is for people. Like, it doesn’t matter that our film has no violence in it. It’s all simulated training programs. The idea of just engaging with the idea of school shootings, mass shootings, is more than a lot of people want to deal with at this point. They just don’t have it in them anymore. We’re hoping that, by coming from a sideways approach, we can reopen some conversations because it’s not a policy or an emotional, heart-wrenching agenda we have. I mean, that’s all part of it, but really, we’re coming from more of a cultural, intellectual, absurdist point of view. We’re posing the questions: does this feel okay? Is this the country we want to be?

AH: To ask more directly, what do you hope people take from this film?

JD: There are two key takeaways that we hope come through in the film. One is that guns are the leading cause of death of children, and that is an American thing and not a global thing. And the more subtle takeaway is that we do want there to be a cultural experience, and we want people to feel angry and disappointed that this is how we are deciding to live, and to question this reality. [I’m thinking of] the metaphor of the frog in the boiling water. It’s just so common that we are all living in it all the time. And so we want to encourage audiences to stop and realize that the water is boiling.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Alexis Haut

Related Posts

Design Juice

Ellen McGirt|Interviews

Making ‘change’ the product: Phil Gilbert on transforming IBM from the inside out

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Interviews

How production designer Grace Yun turned domestic spaces into horror in ‘Hereditary’ and heartache in ‘Past Lives’

The Observatory Newsletter

Delaney Rebernik|Moving Pictures

Fear is a design problem

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Interviews

Beauty queenpin: ‘Deli Boys’ makeup head Nesrin Ismail on cosmetics as masks and mirrors

Recent Posts

The identity industrialists Lessons in connoisseurship from the Golden Globes “Suddenly everyone’s life got a lot more similar”: AI isn’t just imitating creativity, it’s homogenizing thinking Synthetic ‘Vtubers’ rock Twitch: three gaming creators on what it means to livestream in the age of genAIRelated Posts

Design Juice

Ellen McGirt|Interviews

Making ‘change’ the product: Phil Gilbert on transforming IBM from the inside out

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Interviews

How production designer Grace Yun turned domestic spaces into horror in ‘Hereditary’ and heartache in ‘Past Lives’

The Observatory Newsletter

Delaney Rebernik|Moving Pictures

Fear is a design problem

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Interviews

Alexis Haut is an audio producer, writer and educator based in Brooklyn. She spent seven years teaching, leading teachers and coaching basketball in middle schools in Brooklyn and Newark before independently producing her first podcast series in 2018. Her audio work includes the

Alexis Haut is an audio producer, writer and educator based in Brooklyn. She spent seven years teaching, leading teachers and coaching basketball in middle schools in Brooklyn and Newark before independently producing her first podcast series in 2018. Her audio work includes the