May 16, 2011

[WD]All the Taking Things Seriously

Taking Things Seriously, Princeton Architectural Press, 2007

On January 3, 2005, I emailed my friend Carol Hayes, a graphic designer: “My motto this year is ‘Less talk, more rock.’ So I want to get this photo book project going right away. Are you still in?” She was.

The photo book project was one we’d talked about at a party months earlier. I’d been poking around our hosts’ Brooklyn apartment, admiring Joel’s bear lamp and Kelly’s tiny pine cone, and discoursing tipsily on the counterintuitive fact that we enlightened citizens of the 21st century still fall under the spell of savage totems — tutelary spirits, that is to say, in the form of natural objects. Many of us invest ordinary objects with other sorts of extraordinary significance, too. My friend Tony crams a U.S. Navy 100-pound practice bomb into his tiny workspace for much the same reason that Greg, a colleague of mine at the Boston Globe, displays a wobbly wooden Santa in his kitchen year-round. These doohickeys are actually fossils, petrified evidence of a vanished epoch (young adulthood). Other writers, thinkers, designers and artists of my acquaintance cherish things — sunglasses found at a yard sale, a colored-sand-filled glass clown, a one-eyed ceramic frog — for equally irrational reasons.

The more we talked about it, the more we agreed that almost everyone we know reverentially displays in his home or workspace at least one oddball, funny-looking, apparently worthless item as though it were a precious, irreplaceable artifact. Carol’s interest in these objects was more aesthetic than philosophical. Now that every single manufactured object, even garbage cans and soap dishes at Target, are stylish and tasteful, she admitted, it was refreshing to contemplate something tacky, even vulgar, that hadn’t been over-designed and focus-grouped to death. For example: Her friend Lissi’s seven-foot-tall bowling trophy, which she didn’t win bowling; or Deb’s pious porcelain hands, now used as an ashtray; or Kris’s “Sexy Camera,” a shockingly obscene plastic novelty item.

A few drinks later, I picked up an attractive photo book — about New York’s sneaker culture, it turns out — from our hosts’ shelf. It was titled “Where’d You Get Those?” Aha! We’d do a book, some day, about objects with unexpected significance. We’d ask engaged, imaginative, passionate individuals to photograph their significant objects and write us a short essay about where they got them, why they kept them. The resulting collection wouldn’t be a didactic object lesson — like so many “material culture studies” texts written and edited by academics. Taking Things Seriously: 75 Objects with Unexpected Significance, as we would later title it, would instead be a wonder cabinet, a show-and-tell for our fellow enlightened savages.

This essay is an introduction to a series of essays and objects which Design Observer will excerpt from Taking Things Seriously in the coming months. We thank the many authors for their contributions.

An artichoke sat on our kitchen windowsill for months, some years ago. At first, it was ugly and disgusting and kinda gooey — and guests would say “ick.” Then it slowly dried out, changed color, became something else altogether. I’ve now had it for ten years.

I think it’s rather beautiful. I keep trying to use it in a design project, say on the cover of a book. I have photographed it numerous times and created design prototypes featuring this artichoke. They never sell: others do not seem to appreciate the intrinsic beauty of this thing.

Over time it has become more fragile, and I worry that it will break. So it sits, carefully placed, in my bookcase next to some Roman pottery a couple of thousand years older. No one ever touches the older, more fragile pottery, of course. But many pick up my artichoke.

This short essay is excerpted from Taking Things Seriously: 75 Objects with Unexpected Significance, a book by Joshua Glenn and Carol Hayes in which they and other writers discuss the importance of objects in their lives. This is the first essay in a series to appear on Design Observer.

The Aphex Twin Big Bottom Exciter is one of several pieces of recording equipment that sit idly in the corner of my kitchen. As the name indicates, this twelve-by-two-by-two-inch box is designed to excite your bottom. During my DJ phase, that period of Clintonian prosperity and techno-euphoria when all I wanted to do was make “hot” music, the Big Bottom Exciter became a kind of talisman.

I inherited/stole the Big Bottom Exciter from a wealthy friend from college who got caught up in my fascination with beats. I was fortunate to have him as a collaborator because it turned out that “making beats” mostly involved buying equipment. It was in the pages of Future Music that we first laid eyes on the Big Bottom Exciter. I don’t know if it was the allure of getting a whole creative process in a single box or the thrill of recognition that one of our favorite artists was named after this company, but we (he) immediately bought it.

We thought of the Big Bottom as a magic box, like the Echoplex in King Tubby’s studio that he reportedly cured with marijuana to get his signature sound. After putting our music through it, our tapes sounded distorted and crackly, an effect we mistook for “hot.” We covered the logo with duct tape so that no one would know the secret of our sound.

Our sound did not immediately find an audience, nor did it gradually find one. Eventually my partner burned through his inheritance and went to grad school, the Internet bubble burst, Bush got elected, and austerity returned to New York. But even today this box holds promise for me. I feel like if I could just hook it up to other things — my job, my relationship, the news, chores — they would instantly become more exciting and perhaps have bigger bottoms.

This short essay is excerpted from Taking Things Seriously: 75 Objects with Unexpected Significance, a book by Joshua Glenn and Carol Hayes in which they and other writers discuss the importance of objects in their lives. This is the second essay in a series to appear on Design Observer.

When I was seven I lived next door to an exotic old woman and she gave me this Santa. In hindsight, the woman was old and probably a cardiologist — only exotic in the sense that she was very educated and lived next door to us, the unruly Catholics with seven kids. One year she invited the bunch of us over for a little Christmas party, which seemed incredibly fancy to me. There was a long table with a white tablecloth, and cookies that were unlike any I’d ever had, flat with a sickening licorice taste.

After the party the woman gave me and my brother identical Santas, except that mine had a gimpy leg and it wobbled, which seemed right at the time because I saw myself as a victim.

This short essay is excerpted from Taking Things Seriously: 75 Objects with Unexpected Significance, a book by Joshua Glenn and Carol Hayes in which they and other writers discuss the importance of objects in their lives. This is the third essay in a series to appear on Design Observer.

There it was: “THOUGHTS”! How could I not have seen it before? I was sitting at the dining room table in my aunt’s house in Massachusetts when I looked up and noticed this needlepoint sampler for the first time. Holy shit, I almost said out loud. Had it been there for a long time? When did my aunt make it? What was she thinking when she made it? What could it possibly mean?

I have the same inner conversation every time I look at it. Thoughts? Is it thoughts in general, or specific thoughts? Thoughts about a person? Memories? “I’m thinking of you”? Was my aunt trying to express the feeling of going through the mental process of deciding what needlepoint pattern to make next? The sampler’s vagueness plunges me into philosophical confusion. The mystery of it is what attracts me, but it’s also what bothers me. You think thoughts, but how often do you think about thoughts?

My aunt could tell how much I liked the THOUGHTS sampler and a few months after I spotted it she gave it to me as a gift. I took it home and hung it on the wall. Sometimes I would stare at it, and I’d get frustrated every time. Other people who came over and saw it reacted the same way.

My aunt never explained what she meant by THOUGHTS, and I didn’t think it was the kind of question I could ask her. Eventually I had to put the sampler away because it made my head hurt. The idea of my aunt making a picture of the word thoughts in needlepoint amazes me. I never would’ve thought of it. It’s the perfect combination: profound expression and humble craft.

This short essay is excerpted from Taking Things Seriously: 75 Objects with Unexpected Significance, a book by Joshua Glenn and Carol Hayes in which they and other writers discuss the importance of objects in their lives. This is the fourth essay in a series to appear on Design Observer.

I collect First World War artifacts, but not because I am one of these guys who spends his weekends reenacting battles. I have trouble even understanding why someone would want to act out the trench warfare of 1917. This was wholesale slaughter, industrialized and indifferent to individual heroics. Take a number and die. One might as well reenact the Spanish Flu.

I regard this French artillery helmet as a token of monumental disillusionment, a reminder of the greatest-ever failure of enlightened, middle-class, Christian civilization. This was the event where the official narrative — delivered by statesmen, preachers, and leaders of industry — ran so contrary to reality that faith in those institutions was weakened forever.

As it happens, my hometown of Kansas City is the location of a twenty-one-story-high World War I monument and a very large collection of Great War artifacts. As a schoolboy I approached these pieces with the form of patriotic reverence that the museum and the monument embodied. American wars were about freedom, I believed. And honor. And protecting hometowns. It was difficult for the idealistic young me to grasp that what happened on the Western Front was that millions of brave men were ordered to die in an ill-planned and essentially futile conflict.

Today we are in the grip of a different sort of pro-war sentiment, a militarism in which the cynicism is readymade and the disillusionment is build-in, in which our GIs are always said to be betrayed by journalists and (liberal) politicians back home. Whenever some of that angry logic floats my way, I find it helpful to gaze upon that steel helmet and remember the lessons its wearer learned.

This short essay is excerpted from Taking Things Seriously: 75 Objects with Unexpected Significance, a book by Joshua Glenn and Carol Hayes in which they and other writers discuss the importance of objects in their lives. This is the fifth essay in a series to appear on Design Observer.

A German-made plastic pencil sharpener shaped like a TV. Its 3-D screen shows a girl trapeze artist in black tights swinging over a circus crowd. I found it in 1992 in the top drawer of my assigned desk at the American University in Cairo, where I taught English. I used it maybe twice for its stated purpose and gave up because these things never work properly, and I hate pencils.

I’d been living in Egypt just under six months and had adjusted to the noise, the traffic, the poverty, the sheer number of people, and the utter lack of privacy. I regarded this little find as a symbol of my worldliness. So attached was I to it that when a freak earthquake hit Cairo, it was one of the things I found in my hands when I made it outside.

At the time, there was an ad campaign for Tetley Tea on Egyptian television featuring overdubbed footage of Hitler giving a speech. In Arabic, Hitler said something about how England had the ships, America the planes, but “we have the tea!” So my German pencil sharpener took on another meaning: Where the hell was I? What kind of Jew was I to be living in a country where it’s as acceptable to use Hitler to sell beverages as it is for Americans to dress up as Lincoln to sell cars?

Today the pencil sharpener lives in my office, where I do not work as a teacher, or with anything remotely to do with the Middle East. It still has a piece of graphite stuck in it.

This short essay is excerpted from Taking Things Seriously: 75 Objects with Unexpected Significance, a book by Joshua Glenn and Carol Hayes in which they and other writers discuss the importance of objects in their lives. This is the sixth essay in a series to appear on Design Observer.

I received a Grammy award, several years ago, for a CD package I had designed. Receiving a Grammy for a package design is like winning a Nobel Peace Prize for giving up a seat on the subway to an old person.

The ceremony for the lesser awards took place before the live television broadcast. As each winner was announced, we went up onstage, accepted a statuette, and then went backstage where we handed it over to be used for another winner. Some months later, I received one with my name engraved on it. I was particularly impressed with the laser-cut foam in which it had been packaged for mailing — a perfect negative image of the object it was supposed to protect. The foam demonstrates a lot of care and is done with beautiful simplicity. I like to call it the grammyfoam.

The grammyfoam is displayed proudly on a shelf. The award itself is in a box of odds and ends.

This short essay is excerpted from Taking Things Seriously: 75 Objects with Unexpected Significance, a book by Joshua Glenn and Carol Hayes in which they and other writers discuss the importance of objects in their lives. This is the seventh essay in a series to appear on Design Observer.

Everyone who sees this computer cabinet has the same reaction: “What the hell is that thing?” “Oh, just my stereo,” I reply. It’s about five feet tall and three and a half feet wide with Star Trek-era modern brushed aluminum and aquatinted glass doors that weigh about fifty pounds each. A metal label identifies it thusly: Control Data Corporation Peripheral Controller.

I acquired it at a surplus auction at the University of Texas in 1985. I was told the unit had cost a quarter of a million dollars; I got it for ten dollars. I dismantled it, saving all the hardware and labeling the heavy panels, and spent the next ten years hauling the pieces from place to place. Finally, in 1996, I slowly reassembled the thing. In an attempt to justify all the space it took up, I removed most of the circuit boards and modified the interior to hold my stereo and records.

I actually hate modern design — my tastes run to the Victorian and antique — and I’m not too crazy about computers, either. So why am I so fond of this uber-white elephant? I suppose it’s a souvenir of my abortive engineering career and evidence that perhaps I was only interested in the historic and aesthetic aspects of technology all along — I was never going to be happy writing software or solving differential equations. It also reminds me of visiting my dad’s office as a kid, where there were rooms full of similar IBM computers, and my sister and I would spend hours typing out insults on punch cards to amuse ourselves.

Most people have never seen anything like my big, obsolete, all-transistor pre-integrated circuit shell of a computer. Now it’s another antique, an artifact that reminds me of a time when the future seemed both exciting and foreboding.

This short essay is excerpted from Taking Things Seriously: 75 Objects with Unexpected Significance, a book by Joshua Glenn and Carol Hayes in which they and other writers discuss the importance of objects in their lives. This is the eighth essay in a series to appear on Design Observer.

Baudelaire’s death mask gathered dust for years on top of a tall bookshelf in the front hall of my childhood home in Jamaica Plain. When I was a teenager I scaled the shelf one day after school looking for a switchblade that my father, a minister, had once mentioned having confiscated from one of his parishioners. No such luck, but I did appropriate this chipped, tarnished plaster object and hung it above my bedroom desk. It has grimaced sightlessly down upon every desk I’ve had since.

I’ve kept the death mask for a perverse reason: Because it’s the sort of thing one used to notice in the background of photographs of pretentious writers working at their desks. Under the mask’s influence I once spent two impoverishing years slaving over a book about Baudelaire and other thinkers. Like Walter Benjamin, whose Arcades Project started out in more or less the same way, I couldn’t finish it.

The poet and novelist Fanny Howe used to own my father’s house; until recently I believed it was she who’d left the mask there. But now my father tells me not only that he doesn’t know where we got it but also that he never told me whose face it was. After a little research I discovered that it’s actually a life mask of Keats, from the original in London’s National Portrait Gallery. So why did I think Baudelaire?

Perhaps I was influenced by a passage from one of Howe’s novels that I read as a teenager. The protagonist, an ex-political activist turned poet, is asked by a former comrade, “On your death bed, will you be able to say, ‘I helped the poor in their struggle for justice?’ Or will you only be able to quote Baudelaire?” It’s an unfair question, I know. But it’s one that still haunts me.

This short essay is excerpted from Taking Things Seriously: 75 Objects with Unexpected Significance, a book by Joshua Glenn and Carol Hayes in which they and other writers discuss the importance of objects in their lives. This is the ninth essay in a series to appear on Design Observer.

One night in 1991, just before Christmas, I was walking down St. Mark’s Place in Manhattan, heading for my tiny but charming bed-sit on Sixth Street. I’d been around the neighborhood for more than twenty years by then. I remember, for instance, when people started selling stuff on the street, circa 1980. (Earlier, when you found things, you’d either take them home or leave them for others to take; the first harbinger of Reaganomics was when people started selling what they scavenged.) Astor Place became a ’round-the-clock market, delirious and phantasmagoric. It was at once a thieves’ market, a collective yard sale, and the spillway of the collective unconscious.

That night a guy selling old movie posters caught my eye. His prices were high and the sheets were damaged — I surmised he’d fished them from a dumpster. Something made me ask him if he had any incomplete posters. He presented me with a plastic bag full of scraps for ten dollars, one sawbuck. They were rough, vivid, varied, and, because they had come apart along their creases, more or less equal in size. A light bulb appeared directly over my head.

There are pieces of four posters here. Two of them are different advertisements for a single minor horse opera, West of Pinto Pass, circa 1950, starring Crash Corrigan; another is unknown; the fourth is a three-sheet for an early (1962) picture by Elio Petri, writer-director of such 1970s radical head-scratchers as Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion.

During the 1950s, artists in Italy and France cut down layers of movie posters from walls and exhibited them, unaltered, as art. They called their work décollage. In that spirit I propose my untitled piece as the founding work of a new, revolutionary school: démontage.

This short essay is excerpted from Taking Things Seriously: 75 Objects with Unexpected Significance, a book by Joshua Glenn and Carol Hayes in which they and other writers discuss the importance of objects in their lives. This is the tenth essay in a series to appear on Design Observer.

Whatever needed doing at the mortgage company, I did, particularly if nobody else wanted to be bothered. Since I didn’t have my own desk, I floated around, occupying whatever space was handy and empty. This was in the early 1990s, in Pittsburgh. The mad dash to refinance home mortgages had begun to cool. Whole suites were deserted, reminders of a time in the not-too-distant past when the company enjoyed more bullish days.

I searched every desk I sat at not only to fill the periodic lulls but also out of curiosity, to find pieces of other lives, workers before my time. One slow day, while pawing through an abandoned desk, I discovered this rubber stamp and knew immediately that I had to make it mine. Certified True Copy. How strange, I thought, and funny. How could a copy of something ever really be true?

My discovery was luck made manifest. I had recently started writing a story about Copy Copy, a fictional copy shop where a clerk named Tom Again worked the nightshift. Tom dreamed up grand-sounding theories like the Law of Copies, which holds, not originally, that life is but one long and steady decline. An original loses something when copied, Tom posited. A copy of that copy loses a bit more. The law of copies, Tom argued, was the dark twin of the myth of progress. He had ideas, as I had ideas then. And he was stuck, much as I was stuck. I took the stamp, thinking, I’ll incorporate this into my work. I’ll use it. In a moment of misplaced optimism, I even thought it might help me finish the story, like some magic talisman.

It didn’t work. At least not as I hoped. I quit the job, left the story unfinished, and went on to other things.

This short essay is excerpted from Taking Things Seriously: 75 Objects with Unexpected Significance, a book by Joshua Glenn and Carol Hayes in which they and other writers discuss the importance of objects in their lives. This is the eleventh essay in a series to appear on Design Observer.

On a sunny morning in the early 1970s my neighbor, the small shrill widow of a minister and professor of theology at Harvard, dragged me into her house and opened the drawer of her late husband’s desk. Choose, choose anything, she said. From a miscellaneous collection of stuff I took this wedge of brown bread with a label: “Bread given the prisoners at Saar-Alben; and by one of them to me at Luneville Nov. 19, 1918.”

I had never held such a venerable piece of food. The label is always slipping off the diminished lump — but it is the label that evokes ideas of war, capture, suffering, and anticipated salvation either from prison or, because the bread was given to a minister, in the sight of God. Or perhaps the prisoner was simply offering up evidence of the miserable food he had endured. I have no idea why the widow selected me (almost a stranger) to have this bread, but I have kept it as a talisman of the transitory itself — a contradictory talisman, really, for bread is a daily deal, it comes and goes. And it must be fresh. But this bread is antique.

I don’t know that I have always made the right decisions in my efforts to preserve it. About ten years ago, observing its surfaces shrinking as if it were being undermined, I sealed the bread in a plastic bag with a few preservative crystals. Tiny black beetle corpses fell out of the air holes. Then a new kind of hole, like bomb craters, appeared on all sides of the bread, including the darker, smoother crust. The poison that had killed the beetles now threatened to tunnel the bread into nothing. So I sprayed it with a toxic varnish. It survives today as a symbol, though as food it is fit for neither man nor vermin.

This short essay is excerpted from Taking Things Seriously: 75 Objects with Unexpected Significance, a book by Joshua Glenn and Carol Hayes in which they and other writers discuss the importance of objects in their lives. This is the twelfth essay in a series to appear on Design Observer.

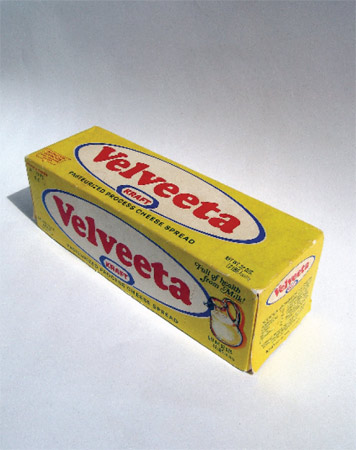

When I was sixteen or seventeen, I had a huge argument with my father. For me, that fight was a turning point in our relationship; for him, though, it was just one of a series of disagreements with his nagging daughters. I had been clearing out the clutter that had been accumulating in our home since the untimely death of my mother years before. But then I discovered that my father — a renowned professor of archeology, history, and theology at Boston College — was trash-picking those very items and bringing them back inside.

I remember holding up an empty cheese-food box and arguing passionately against the item, saying it had no purpose. But my father wouldn’t back down. He insisted that “Velveeta boxes are good boxes, well-made, and you can keep things in them.” At that moment, I realized that if I couldn’t even win the Velveeta box argument, then the arguments over the used typewriter cartridges, the orange juice container tops, and the bags of bags of bags — not to mention the rubber bands, napkins, little soaps, and twist-ties — were futile.

Flash-forward to twenty years later: I am helping my now-retired father unpack his belongings following his move to Los Angeles. I open a crate and sitting on top of its contents is a Velveeta box whose purchase-by date reads “1982.” My father had used it to store cord. Twenty years and three thousand miles: He won.

This short essay is excerpted from Taking Things Seriously: 75 Objects with Unexpected Significance, a book by Joshua Glenn and Carol Hayes in which they and other writers discuss the importance of objects in their lives. This is the thirteenth and final essay in a series to appear on Design Observer.

Observed

View all

Observed

By The Editors

Related Posts

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

The Observatory

Ellen McGirt|Books

Parable of the Redesigner

Arts + Culture

Jessica Helfand|Essays

Véronique Vienne : A Remembrance

Recent Posts

Mine the $3.1T gap: Workplace gender equity is a growth imperative in an era of uncertainty A new alphabet for a shared lived experience Love Letter to a Garden and 20 years of Design Matters with Debbie Millman ‘The conscience of this country’: How filmmakers are documenting resistance in the age of censorshipRelated Posts

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

The Observatory

Ellen McGirt|Books

Parable of the Redesigner

Arts + Culture

Jessica Helfand|Essays

Design Observer is edited by Michael Bierut and Jessica Helfand, with assistance from Betsy Vardell, Elizabeth Deverereaux, Chappell Ellison and Joanna Radin.

Design Observer is edited by Michael Bierut and Jessica Helfand, with assistance from Betsy Vardell, Elizabeth Deverereaux, Chappell Ellison and Joanna Radin.