July 21, 2010

Wild at Heart: Tadanori Yokoo

Tadanori Yokoo (b. 1936) has embraced an enormous variety of media — book designs, animation, prints, posters, album covers, Swatch watches, illustration and paintings. All of his works display a unique visual richness, alluding to a massive and eclectic array of artistic images and movements: Surrealism, Dada, Russian Constructivism, American Pop Art, contemporary Japanese popular culture and traditional Japanese art forms, especially the woodblock prints known as ukiyo-e. Few artists of any medium have succeeded so well in capturing the visual inundation that comes from living in large, cosmopolitan cities. As Yokoo himself put it, “When I walk through the streets of Tokyo, it is not unusual for me to weave back and forth as if I were recovering from an illness.” His intricate, dreamlike designs are portraits of our turbulent and chaotic times that embrace both the high and low as well as burgeoning globalization.

In the West, printed works have been traditionally produced for artistic contemplation or functional purposes, but rarely for both. A poster might advertise a product, an event, a safety warning or a political cause in the Soviet Union, Switzerland, Poland or the U.S. But in all such cases, urgent communication is far more important than leisurely contemplation. In Japan, beginning with the production of ukiyo-e in the late 17th-century, which were both commercial advertisements for the merchants of a rising middle class and cherished art objects, there have been no such divisions.

Yokoo descends from the murky overlap between art and design. His work, like that of many of his Japanese contemporaries, is exquisitely printed in small runs. For example, his 1971 poster for the Bunraku Play of Chinsetsu Yumihari-zuki at the National Theater in Tokyo bears no resemblance to the dull offset theater broadsides seen in Europe or the U.S. A simple black background is overprinted with an outline of Hokusai’s “Great Wave” then printed again with a barely visible samurai battle scene. Holes appear as if shot through the poster in the upper regions, and details of the event are rendered in calligraphy.

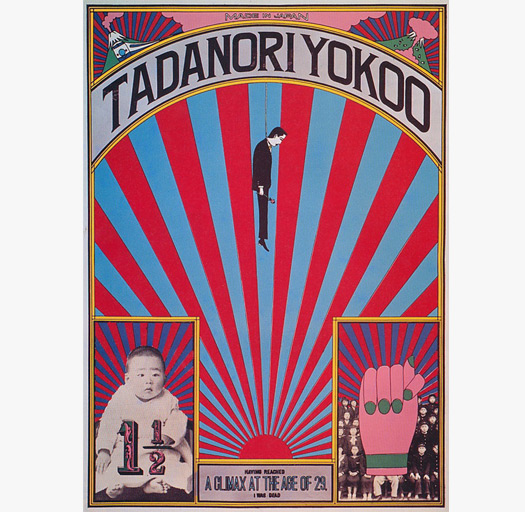

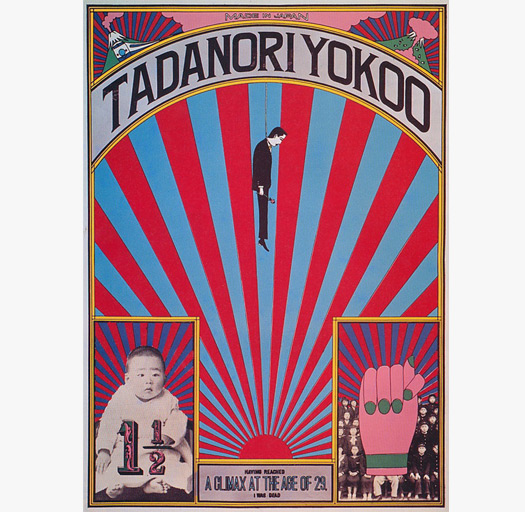

Yokoo’s most expressive image is also one of his most controversial. In 1965, he created the poster “Made in Japan, Tadanori Yokoo, Having Reached a Climax at the Age of 29, I Was Dead” to promote an exhibition of his work. He would return again and again to many of the visual motifs used here — Mount Fuji, the rising sun, a speeding Shinkasen train. The train represented postwar Japan’s rapid and ultimately problematic development, which some felt had destroyed the country’s nobler traditional culture. Mount Fuji stood for that old world, and the rising sun symbolized the militaristic folly that led to Japan’s modern condition. On the bottom of one side of the poster is a photograph of Yokoo as a baby and on the other a school picture with a hand expressing an obscene gesture. In the middle is a young man hanged with a flower in his hand. The strong suggestion is that Yokoo had decided to take his own life having reached a sexual climax. Some believed at the time that he had really died.

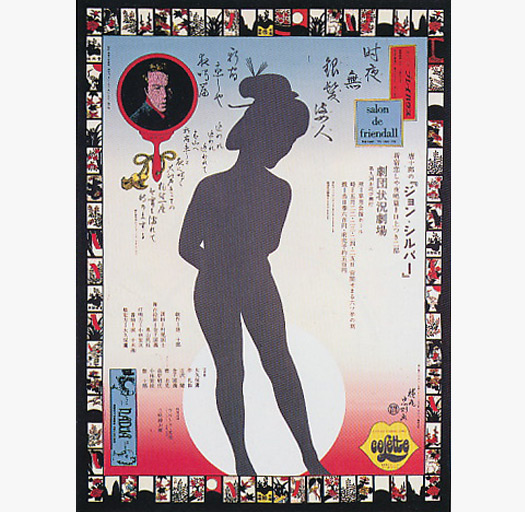

The particularity of Yokoo’s content often led him to inscribe personal messages. A 1967 poster for the play “John Silver” contains his apology to the director Juro Kara for turning in the work late. A 1998 poster for “Counter Attack,” an exhibition of his work at the Tokyo department store Takashimaya includes images of geishas; large floating mouths, some with braces; a Hokusai wave; money; a legendary Japanese boy born from a peach; the rising sun. Like Aleksandr Rodchenko’s photomontages for Vladimir Mayakovsky’s poetry book Pro Eto (For You), these are visual poems, with each stanza its own image but without a fully coherent narrative.

Humor — sophisticated, dry, thoughtful and self-deprecating — is also a powerful element in his work. “A Ballad Dedicated to the Small-Finger Cutting Ceremony” (1966) features a yakuza’s hand missing its pinkie and blood streaming across the image. The 1971 “Wonderland” poster series for a Japanese resort presents nude Scandinavian beauties beckoning to Japanese men as they sit on heaps of Danish cheese surrounded by sexually suggestive plants and animals. “First Planning” (1996), a poster for a family planning organization, is a medley of intertwined cranes, fornicating cats, an open bottle of sake and a drunk Buddha, slyly suggesting the correlation between alcohol and unwanted pregnancies.

Part of the complexity in Yokoo’s posters reflects the artist’s social, economic and political milieu. Japan has roiled with calamity and reparation, from its disastrous defeat in World War II and occupation by American forces, through its transformation from enemy to ally, to its stupendous postwar economic development, resulting in one of the world’s largest and most successful economies. That economy has cooled substantially over the last two decades, but it remains formidable. Additionally, the easing of Japan’s xenophobic tendencies came with globalization of much of its popular culture. Paramount in Yokoo’s work is the questioning of the relationship between traditional Japan and the West and between the new Japan and the old. Nationalistic pride is tempered with the embarrassment of tragic militaristic aggression, evidenced by Yokoo’s almost signature-like use of the rising-sun motif, an image banned in his country from 1945 to 1954. His repeated use of the “peach boy” is a metaphor for Japan’s postwar growth. (The symbol draws from an Edo-period folktale in which a long-childless couple finds a large peach and upon opening it discovers a lovely baby boy.)

Another influence on Yokoo was simply the tremendous vibrancy of Tokyo’s postwar art world. As Alexandra Munroe, a curator at the Guggenheim Museum, has written, the ’60s marked “undoubtedly the most creative outbursts of anarchistic, subversive and riotous tendencies in the history of modern Japanese culture.” Yokoo was part of a Tokyo avant-garde testing disciplinary boundaries and even the question of what constituted art. Members of this group included the filmmaker Nagisa Oshima, playwright-filmmaker Shuji Terayama, author Yukio Mishima and artists Yayoi Kusama and Yoko Ono. Reacting to Tokyo’s ravaged postwar condition and the destruction of much of its material culture, the artists in this group worked with ephemeral media and regarded themselves unconstrained by the notions of idealism and permanence in fine art.

In this maelstrom, Yokoo found a reason and opportunity to challenge the hierarchical nature of Japanese society and what the Tokyo-based journalist Donald Richie describes as its “invisible networks of deference, obligation and taboo.” A picture of Tarzan fits comfortably in a Yokoo landscape filled with classical Japanese images. A famous female Japanese movie star is undressed and bound in his work. Even Jesus is deputized to sell household appliances. The smart rebel who pokes fun at the stuffy establishment is common to Dada and Pop Art, too, but this persona feels especially invigorating in the context of modern Japan.

And you can count on Yokoo’s dependability. Few artists who came to prominence in the 1960s and ‘70s, as Yokoo did, still produce important work, if they continue working at all. The immensely talented Ono left Japan for the U.S. and took on the very public role of John Lennon’s wife. Kusama cut herself off from the world. Mishima committed suicide. And Oshima began making more conventional films. Yokoo, however, continued experimenting, and his work still challenges orthodoxies, pushes boundaries and tries to help Japan to see a world beyond itself.

Key to his experimental nature is the freedom with which he uses collage, playing with scale, mixing photography with illustration and tossing a vast array of images into his compositions. If one can interpret modern graphic design as a history of collage — beginning in the 1910s with the introduction of photography, photomontage and newly liberated typography and culminating in the late 1980s with the digital era — then Yokoo’s posters might even be classified as a finale. He has advanced the medium to a natural end point in terms of the possibilities for variety and eclectic character.

Although Yokoo is a treasured cultural icon in Japan, ihe has not received his proper due in the West. Issey Miyake, Yohji Yamamoto, Akira Kurosawa, Arata Isozaki, Tadao Ando, Rei Kawakubo, and, more recently, Yoshitomo Nara, Haruki Murakami, Takashi Murakami and Hayao Miyazaki all have greater name recognition. They are identified with professions or art forms with which we are familiar — author, architect, fashion designer, fine artist, and filmmaker — whereas Yokoo’s career is singular in scope. Even after knowing and admiring him for 25 years, I still am unsure exactly how to describe his vocation to other Americans. Artist, graphic designer, printmaker, illustrator — none is really adequate or accurate.

Yokoo’s lack of celebrity in the West is particularly ironic given the recent popularity of anime, manga and other Japanese entertainments. American collectors seize the creations of Takashi Murakami and Yoshitoma Nara, and yet Yokoo was the progenitor of these artists. His use of exaggerated flat images and his seamless synthesis of eastern and western pop culture predated Murakami’s by 25 years. And much is owed to him for the balance and conflict between the beautiful and grotesque that characterizes a great deal of current Japanese art.

I can still remember the first time I saw Yokoo’s posters, in a storage container, at The Museum of Modern Art. I was in my early twenties, fairly recently employed by the museum and awestruck by objects that I couldn’t imagine existed. I fell in love with the vibrant content and colors and the incomprehensible symbols and pure beauty. I still have that reaction today. In 2002, Yokoo was asked, “If you were to retire tomorrow, what would you do with your free time?” He responded, “Retirement will come only with death. Already I am looking forward to my posthumous time.” For this, the whole world should be grateful.

Adapted from Christopher Mount’s catalog raisonne essay for “The Complete Posters of Tadanori Yokoo,” an exhibition running through September 12, 2010, at the National Museum of Art in Osaka, Japan. The catalog, which includes more than 800 of Yokoo’s works from the past half-century, is published by Kokusho Co., Japan. Text is in both Japanese and English.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Christopher Mount

Related Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

“Dear mother, I made us a seat”: a Mother’s Day tribute to the women of Iran

Recent Posts

Minefields and maternity leave: why I fight a system that shuts out women and caregivers Candace Parker & Michael C. Bush on Purpose, Leadership and Meeting the MomentCourtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packagingRelated Posts

Business

Courtney L. McCluney, PhD|Essays

Rest as reparations: reimagining how we invest in Black women entrepreneurs

Design Impact

Seher Anand|Essays

Food branding without borders: chai, culture, and the politics of packaging

Graphic Design

Sarah Gephart|Essays

A new alphabet for a shared lived experience

Arts + Culture

Nila Rezaei|Essays

Christopher Mount is an independent curator, writer, art advisor and educator specializing in 20th-century architecture, design and graphics.

Christopher Mount is an independent curator, writer, art advisor and educator specializing in 20th-century architecture, design and graphics.